Yves here. Covid’s impact on the labor market (early retirements, avoidance of certain workplaces, long Covid) has had an upside: giving people with disabilities jobs. Despite the fact employers are not supposed to discriminate against those who have a disability, they still often have trouble getting hired. I’ve even seen an example in Mountain Brook, with our normally image conscious local gym hiring a woman for the front desk who has a mild speech impediment and gets around with a motorized wheelchair.

By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

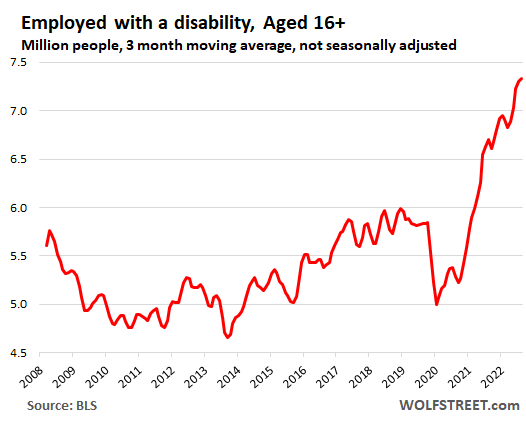

The tight labor market over the past two years has had an amazing effect on people who have a disability: An additional 1.55 million were working in January, compared to the pre-pandemic January 2020, up by 27%, according to the employment data by the Bureau of Labor Statistics today.

And according to the Social Security Administration, the number of people who applied for disability benefits, and the number of people who received disability benefits, both dropped to the lowest levels in many years.

In January, there were 32.6 million people aged 16 and over who had a disability, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Lots of times, you see the word “the disabled,” but that’s wrong. Many of them are not “disabled.” The correct term is “people with a disability.” They may be vision impaired, or they returned from a war with a limb blown off, or they have some disease. A lot of disabilities are the natural result of getting old. Many of the lucky ones that make it to 80 years have some kind of disability, and yet some still work and earn money, and you’ll find some in the US Congress, making good money too.

Others are elderly and retired; others receive disability benefits and are not working; others are wealthy and don’t need to work; others are full-time students, etc.

The number of people with a disability in the labor force started spiking with the tight job market in early 2021, which encourage people with a disability to go look for work, and thereby join the labor force.

A record 7.85 million people with a disability were in the labor force in January, meaning there were either working or actively looking for a job in January. This was up by 24%, or by 1.62 million, from January 2020!

At the same time, in this tight labor market, companies, beset with difficulties in hiring people to fill the record number of job openings, began opening more doors to people with a disability. (None of the data here is seasonally adjusted. To reduce some of the month-to-month variations, I used three-month moving averages):

The number of people with a disability who were employed in January spiked by 27% from January 2020, to 7.29 million in January — with December at 7.37 million having been the highest in the data from the BLS going back to 2008:

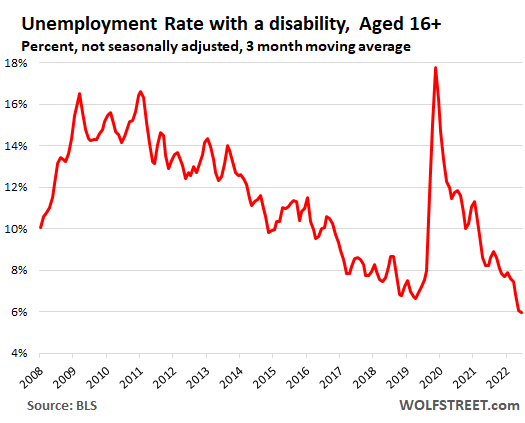

The unemployment rate for people with a disability — people who were unemployed and were actively looking for a job — dropped to a record low of 5.0% in December, not seasonally adjusted, amid a surge of seasonal hiring by the retail industry before the holidays. In January, those seasonal jobs ended, and the unemployment rate rose of 7.1%.

The three-month moving average of the unemployment rate, which irons out the month-to-month fluctuations, dropped to 6.0% in January, the lowest in the data going back to 2008.

However, the unemployment rate for people with a disability remains far higher than for the overall labor force (3.5% in December and 3.4% in January, seasonally adjusted), attesting to the difficulty people with a disability face in getting hired even in a hot labor market.

People with a disability who want to work face a harsh reality: Finding a job is tougher for them than for people without a disability. And so the unemployment rate is always higher. But as the labor market got historically tight, employers were encouraged to hire people with a disability, and people with a disability were encouraged to look for a job. The results are great to see.

Here is the thing: Over the past two years, people with a disability added 1.62 million more workers to the labor force, even as the overall labor force has not been able to recover to pre-pandemic trend due to excess deaths, a wave of retirements, and other factors, which has been dogging this labor market for the past two years.

People Applying for and Receiving Disability Benefits

There is another aspect to disability: People who apply for disability benefits with the Social Security Administration, and then the people who actually receive disability benefits.

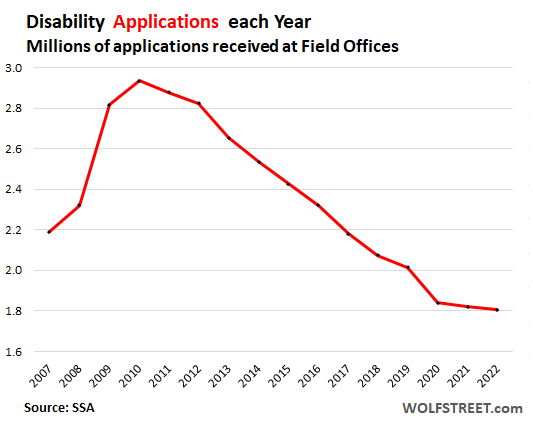

During the Great Recession, in a phenomenon that has long been discussed, applications for disability benefits spiked. Many of them might have been people with a disability who tried to find a job but couldn’t as the labor market went into crisis, and so they gave up and applied for disability benefits. Applications for disability benefits, received by Social Security Administration field offices, peaked in 2009 at the peak of the unemployment crisis, with 2.94 million applications.

Every year since then, the number of applications dropped and in 2022 fell to 1.80 million applications at the field offices, the lowest since 2003:

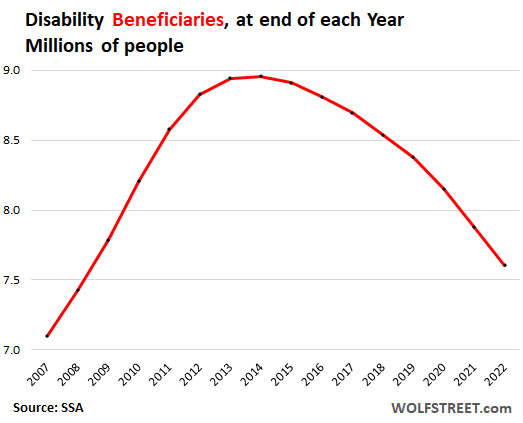

The number of people who actually received disability benefits peaked in 2014 at 9.0 million beneficiaries and has since then dropped every year. In 2022, it dropped to 7.6 million, the lowest since 2008: