Yves here. The mortgage guarantee giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are implementing changes to their fee structure starting May 1 which crudely speaking increase fees for high credit score borrowers and lower them for weaker credit score borrowers. But as Rajiv Sethi, that simplification isn’t completely accurate (some high credit score borrowers fare better under the new rules) and some of the commentary is so wrong as to look mendacious, as opposed to ignorant.

By Rajiv Sethi, Professor of Economics at Barnard College, Columbia University and an External Professor at the Santa Fe Institute. Originally published at Imperfect Information

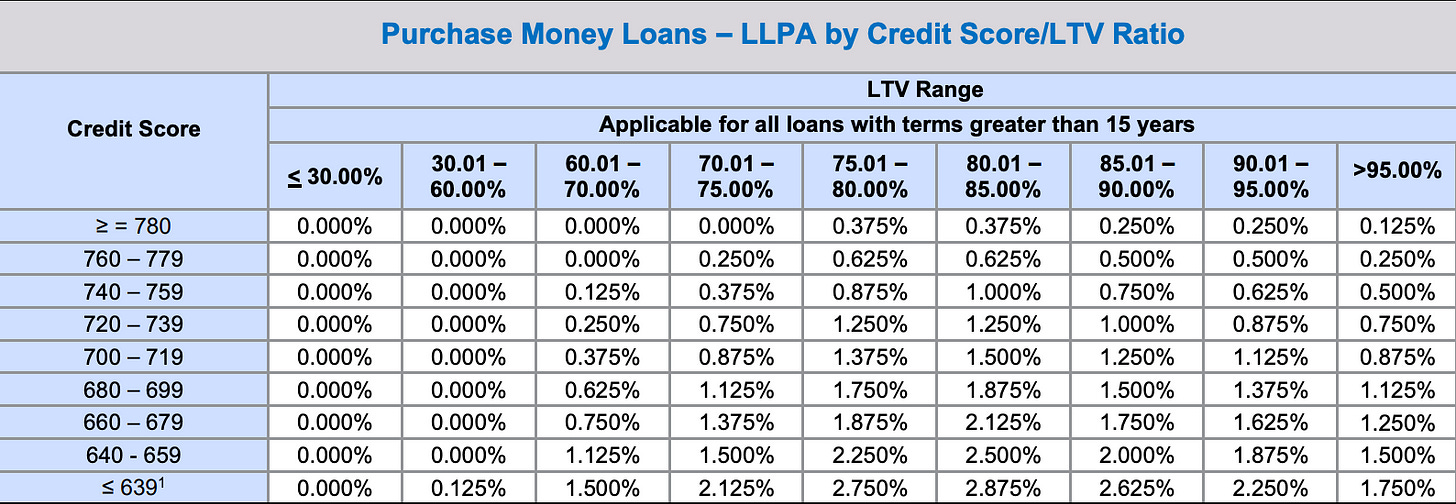

Mortgage originators in the United States typically sell off their loans in the secondary market, where the main buyers are the government sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These agencies levy surcharges called loan level price adjustments (LLPAs), which affect the eventual prices paid by home buyers. The surcharges depend on a number of factors, including the borrower’s credit rating and the mortgage loan-to-value ratio. Generally speaking, lower credit ratings and higher loan-to-value ratios correspond to riskier mortgages, which have historically been associated with higher fees.

A change in the fee structure that is due to go into effect on May 1 has resulted in a lot of animated commentary, blending together factual reporting with some exaggeration, distortion, and outright falsehood. According to one report, an (unnamed) executive from a mortgage lending company complains that “we have to teach borrowers to worsen their credit before they apply for a mortgage in order to get the better price.” Advice on how exactly to do so has started to appear online.

If it were really the case that one could get a cheaper loan by sabotaging one’s own credit rating, the policy changes would indeed be absurd. In the language of mechanism design, the new fee structure would fail to be incentive compatible, and all manner of chaos would ensue. Consultants (and charlatans) would step into the breach to profit from advising potential borrowers on the quickest, cheapest, and most easily reversible ways of appearing less credit-worthy.

But this is not what the changes entail. Having a good credit score continues to confer an advantage under the new fee structure, although to a diminished degree at some levels of the loan-to-value ratio. That is, fees have been reduced for borrowers with lower credit scores and raised for those with higher scores, in a manner that compresses the difference without erasing or reversing the earlier advantage.

That said, there are some puzzling changes in the fee structure as it relates to loan-to-value ratios, and it’s worth a closer look at these. First, here are the current loan level price adjustments, set to expire at the end of the month:

Note that in each column, rates rise as as one moves down towards lower credit scores. And in each row, rates rise as one moves right towards higher loan-to-value ratios (corresponding to lower down payments relative to the value of the property). That is, riskier loans are costlier. The only exceptions are at the 80% loan-to-value threshold, corresponding to a 20% down payment. Here, the fees fall slightly as one moves to the adjacent column on the right, for those with credit ratings at or above 680. Presumably this reflects the fact that those making down-payments below 20% are required to purchase private insurance, making the loans less risky for lenders. This is not necessarily a violation of incentive compatibility, although one can imagine cases in which it pays to offer a down payment slightly below the threshold.Now consider the new fee structure, which goes into effect next month:

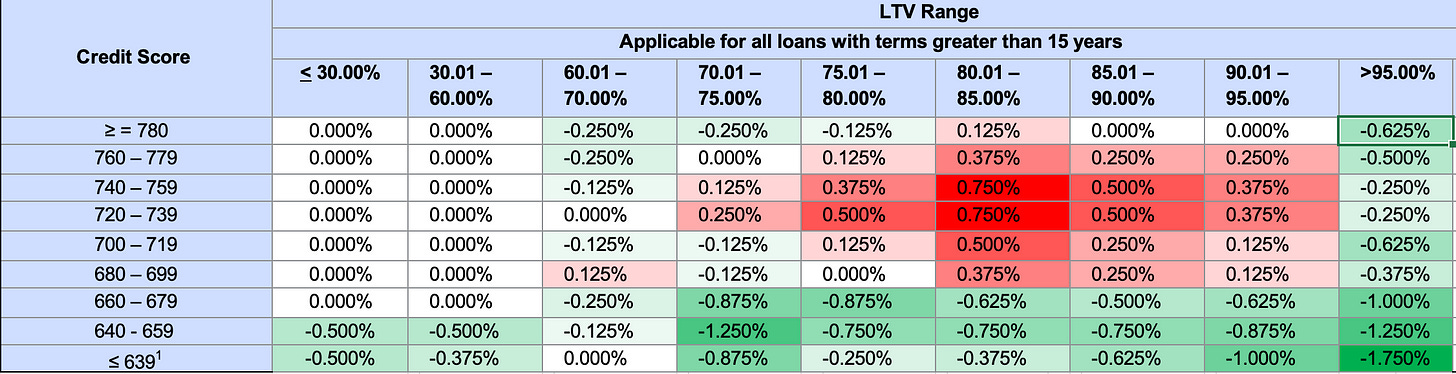

Notice that credit scores below 639 have been consolidated into a single row, and those above 740 have been split into three. In addition, loan-to-value ratios at 60% and below are now in two separate columns rather than one. This makes direct visual comparisons a little difficult, but one thing is clear—at no level of the loan-to-value ratio does someone with a lower credit score pay less than someone with a higher score. That is, one cannot gain by sabotaging one’s own credit rating.

In general, there are two types of borrowers who stand to gain under the new fee structure: those with low credit scores, and those with low down payments. In fact, those at the top of the credit score distribution gain under the new structure if they have down payments less than 5% of the value of the home. The following table shows gains and losses relative to the old structure, with reduced fees in green and elevated ones in red (a comparable color-coded chart with somewhat different cells may be found here):

What might the rationale be for rewarding those making especially low down payments? Perhaps the goal is to make housing more affordable for people without substantial accumulated savings or inherited wealth. But there will be an unintended consequence as those with reasonably high credit scores and substantial wealth choose to lower their down payments strategically in order to benefit from lower fees. They may do so by simply borrowing more for any given property, or buying more expensive properties relative to their accumulated savings. The incentive to do so will be strongest for those hit hardest by the changes, with credit scores in the 720-760 range and down payments between 15% and 20%.

I wonder if the designers of the new policy have taken proper account of this strategic effect, which will tend to hollow out some of the cells in the middle and populate the ones on the right.

Taking all this into account, how should the changes be evaluated? Despite some provocative and overly simplistic headlines, the merits of the new fee structure are debatable, and our assessment ought to depend on the default risks associated with each loan category as well as the overall goals of the program itself. After all, the rationale for having GSEs play a role in the mortgage market has always been tied to creating conditions for borrowers who would otherwise struggle to secure loans. Such initiatives inevitably involve some degree of cross-subsidization. For instance, our medicare taxes are not linked to our health status, life expectancy, or the likelihood that we will require especially expensive care in later years. Complaints about the new fee structure seem to implicitly assume that the structure it replaces was perfectly aligned with the goals of the program. But this itself is a debatable proposition.

Some clarity from the administration regarding not just their goals but precisely how the changes in fee structure are expected to meet those objectives without deleterious side effects would be quite welcome at this stage. Otherwise a policy change that may well have some merit will be very easily misrepresented and demonized.