Yves here. An analysis of the fallout from California’s big snow, which was generally welcomed for its potential to replenish declining water levels in reservoirs. But a sudden warm spell, which is what much of California will seeing, means a fast runoff, which can produce both floods as well as the water going straight into waterways and therefore into the ocean, as opposed to groundwater and caches.

By Jeff Masters. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

Floodwaters swallow a county road at California’s Tulare Lake, which has inundated dozens of square miles of farmland this spring. Gov. Gavin Newsom visited the area on April 25 to provide an update on response and flood operations. (Image credit: Office of the California Governor)

-storm category-feature-articles category-weather tag-bob-henson entry”>

As they watch for a spring heat wave set to arrive in the final days of April, Californians are bracing for the first big surge of flooding from a near-record snowpack. Abundant spring sunshine and near-record temperatures in the 80s and 90s Fahrenheit were predicted to stretch from Thursday through the final weekend of the month.

Daily record highs of 93°F in Sacramento and Redding may well be topped on Friday, and some record-warm daily minimums are possible as well. By Sunday, temperatures could approach 100°F in parts of the southern San Joaquin Valley.

Temps 20 deg above normal expected. Shown is the Climate Shift Index from Climate Central. The unusual warmth will accelerate melting of this year’s historic Sierra snowpack, increasing the risks of severe flooding and landslides, particularly in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

pic.twitter.com/BMcJZfd5Ms

— Jeff Berardelli (@WeatherProf) April 26, 2023

The vast bulk of the water trapped in this winter’s snowpack is still in place. As sunshine intensifies from now through June, it will not only warm the air but also prime the snowpack for periods of rapid melting. It’s the timing and strength of these unusually warm, sunny periods — plus the arrival of any final wet storms of the season — that will determine the seriousness of river flooding over the next few weeks. Extended models suggest a cloudy, cool period will likely extend for at least a week or so after the late-April heat abates.

“Any additional early heat waves or major warm rain events between now and early June would still have the potential to cause even greater challenges,” noted Daniel Swain of the University of California, Los Angeles/National Center for Atmospheric Research in his Weather West blog.

The worst of the snowmelt floods are expected to hit the southern San Joaquin Valley, westward and downstream of the southern Sierra slopes where the most extreme snows of winter 2022-23 fell. This spring’s signature flooding has inundated large parts of the 690-square-mile Tulare Lake basin, at the south end of the huge San Joaquin Valley of central California. Once the nation’s largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River, Tulare Lake almost completely disappeared in the late 19th and early 20th century as water diversions opened the lake bed up to agriculture.

This year, the lake has reasserted itself, mushrooming to cover more than 100 square miles and triggering conflict across the region. Several farming communities are at risk as well as billions of dollars in agriculture. Parts of the Tulare Lake basin are predicted to remain flooded for as long as two years, as was the case after the back-to-back wet years of 1981-82 and 1982-83 (see below).

“This weather whiplash is what the climate crisis looks like — and that’s why California is investing billions of dollars to protect our communities from weather extremes like flooding, drought, and extreme heat,” said California Gov. Gavin Newsom during a visit to the Tulare Lake basin April 25.

Farther north, the snowpack of the central and northern Sierra isn’t quite as anomalous as in the southern Sierra, but any periods of rapid melt could bring localized river flooding there as well.

Ensemble modeling indicates a greater-than-40% chance that snowmelt will push the Merced River at Pohono Bridge in Yosemite National Park into at least moderate flood stage (12.5 feet) by Sunday, April 30. Most of the valley within the park will close from 10 p.m. PDT Friday, April 27, through at least May 3, according to the park’s website, which added: “It is very likely that the Merced River will reach flood stage off and on from late April through early July.”

Yosemite’s most extreme floods are typically driven not by spring snowmelt but by intense winter rainstorms. That was the case with the catastrophic record floods of January 1997 as well as in February 2023, when the park was closed for weeks after 21 inches of precipitation fell over 21 days.

As announced yesterday, much of Yosemite Valley will close starting Friday, April 28, at 10 pm, due to a forecast of flooding. Western Yosemite Valley will remain open but could close if traffic congestion or parking issues become unmanageable. (1/3)

— Yosemite National Park (@YosemiteNPS) April 27, 2023

One huge plus of the immense snowpack: Water resources will be the most abundant in years. The California Department of Water Resources announced April 20 that it will be able to supply 100% of requested water supplies for the first time since 2006.

Figure 2. A drone provides an aerial view of a cloud mist formed on March 17, 2023, as water flows over the four energy dissipater blocks at the end of the main spillway at Lake Oroville. The California Department of Water Resources announced Wednesday, April 26, that inflows from the lake to the Feather River will rise to 20,000 cubic feet per second on Thursday. The lake was at 90% of storage capacity and was last at full capacity in 2019. Both the main and emergency spillways of Lake Oroville were damaged in February 2017 after heavy rainfall, and more than 180,000 people downstream were ordered to evacuate. (Image credit: California Department of Water Resources)

Recreationalists Beware: This Summer’s Cold Water Will Be Dangerous

Regardless of spring flooding, rivers are expected to run high and cold throughout the summer, and state officials are already concerned about adventurers getting into dire trouble. Even moderately cold water around 50-60°F can produce “cold shock” and greatly compromise breath and muscle control well before hypothermia develops.

The American Heart Association cautions that it’s misleading to assume from polar-plunge events that one can easily survive frigid water, as participants in those events are typically only waist-deep and only for a brief period. The situation is far different when you’re suddenly and fully immersed in cold water — such as after capsizing from a kayak — and you’re likely panicking and gasping for breath. In such a situation, even experienced swimmers can quickly get into mortal danger.

“Cold shock and swimming failure can cause you to drown in a matter of seconds,” warns the National Center for Cold Water Safety in a sobering set of explainers.

A late week warmup will induce a strong snowmelt response for areas near and below 7500-8500 feet. Area streams, creeks and mainstem rivers will run at or above bank full, and will be fast and cold as a result of melting snow. https://t.co/mPY0GJdMVw. pic.twitter.com/dlS1QwVxok

— NWS Reno (@NWSReno) April 24, 2023

Was This a Record Snow Year for California? It Depends

Overall, California’s statewide snowpack ended up among the five heaviest in all winters going back to 1950, based on records from the state Department of Natural Resources. Exactly where a particular year ranks depends on how the records are parsed. This is often the case with global monthly temperature analyzed by NOAA, NASA, and other agencies (as we note each month) and a data-journalism analysis by the San Jose Mercury-News now confirms that the same is true for California snowpack.

While many reports said that 2022-23 had the second-largest snowpack on record behind 1951-52, the Mercury-News pegged 2022-23 as No. five. The journalists noted that the snow data from 1951-52, which ranks first in the state list, included several typically-snow-sparse areas that weren’t normally included in the state survey.

After adjustments, the Mercury-News team found that the top-five snow years since 1950 were unchanged (1951-52, 1968-69, 1982-83, 1994-95, and 2022-23), but they were arranged in a different sequence, with 1982-1983 coming out on top.

The team’s work also reinforced a key point about climate-change analysis: The baseline of what we consider “normal” is shifting. Standard practice is to use the most recent three decades (e.g., 1991-2020) as the best long-term average. When snowpack is instead evaluated against California’s entire 1950-2023 data set, then a long-term decline in snowfall comes into sharper relief.

One thing that’s clear: With water equivalent in snowpack of up to 300% of average, the southern Sierra had its snowiest year in modern records.

What About Next Winter?

There may not be much time for California to dry out before the expected arrival of El Niño later this year. The effects of El Niño and La Niña can vary dramatically from event to event, as emphasized by veteran Bay Area meteorologist Jan Null of Golden Gate Weather Services. Even one of the strongest El Niño events of the past 75 years, 1987-88, was drier than average in California.

In general, though, stronger El Niño events do tend to produce wetter-than-average conditions for California. That’s particularly true for the southern half of the state — which happens to be the hardest-hit area this year as well.

Will El Niño bring more AR storms to West Coast?

— Wonder Woman (@lulabelldesign1) April 20, 2023

“We’ve not seen back-to-back very wet winters in California in the modern era,” Swain noted in a YouTube briefing April 24. “We’ve seen a lot of back-to-back dry winters, but not the reverse.”

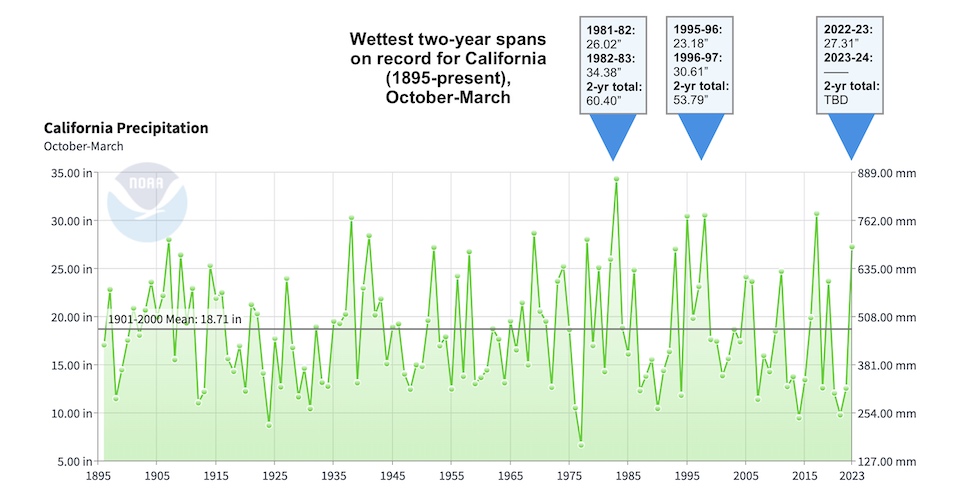

California’s statewide precipitation from October 2023 through March 2024 was 27.31 inches, which ranks as the 10th-wettest out of the 128 such periods in NOAA record-keeping. Across a typical state water year (October to September), more than 80% of all precipitation has been received by the end of March.

As shown in Figure 3, the wettest two-year period in California records for October-March was 1981-1983. This included the ENSO-neutral winter of 1981-82 and a very strong El Niño of 1982-83. The second wettest pair of October-to-March periods was 1995-97, which adhered to a similar pattern: a cool-neutral winter in 1995-96 followed by the very strong El Niño of 1996-97. The only other comparably potent El Niño event of modern times, 2015-16, was preceded and followed by drier-than-average winters.

If as much precipitation falls next October to March as just fell in those six months, then the period 2022-24 would jump into second place. In order for 2022-24 to hit first place, October 2023 through March 2024 would need to yield 33.09 inches.

Hitting that threshold would be a tall order. Still, for prudence’s sake — and assuming that a robust El Niño arrives as expected later this year — it’s smart to at least anticipate the chance that 2022-24 could approach 1981-83 as one of the wettest two-year sequences in California history.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.