We first wrote about what came to be called about deaths of despair when the landmark work by Angus Deaton, the 2015 Nobel prize winner in economics, and his wife Anne Case, on the dramatic rise in the death rate of middle-aged, less educated whites. Even though this study and a follow-on did garner a great deal of major media attention, there was almost nothing in the way of action to try to alleviate this crisis.

The cancer of inaction seems to be working its way through its host, as in the US. The Wall Street Journal reports tonight Young Americans Are Dying at Alarming Rates, Reversing Years of Progress. You’ll see many of the causes parallel those of lamented but not acted upon deaths of despair. And as you’ll also see. both tragedies are acute in the US, not so much in other advanced economies.

For a refresher, from our first post in 2015 on Case-Deaton findings:

The authors found that from 1999 to 2013, the death rate among non-Hispanic whites aged 45 to 54 with a high school education or less rose, while it fell in other age and ethnic groups. This is an HIV-level silent epidemic: AIDS killed an estimated 650,000 from the mid-1980s to present, while an estimated close to half-million died in half that time period who would have lived had their mortality rates fallen in line with the rest of the population. It is hard to overstate the significance of these findings. From the New York Times:

“It is difficult to find modern settings with survival losses of this magnitude,” wrote two Dartmouth economists, Ellen Meara and Jonathan S. Skinner, in a commentary to the Deaton-Case analysis that was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

This cross-country comparison from the study shows how extreme an outlier these middle aged whites are:

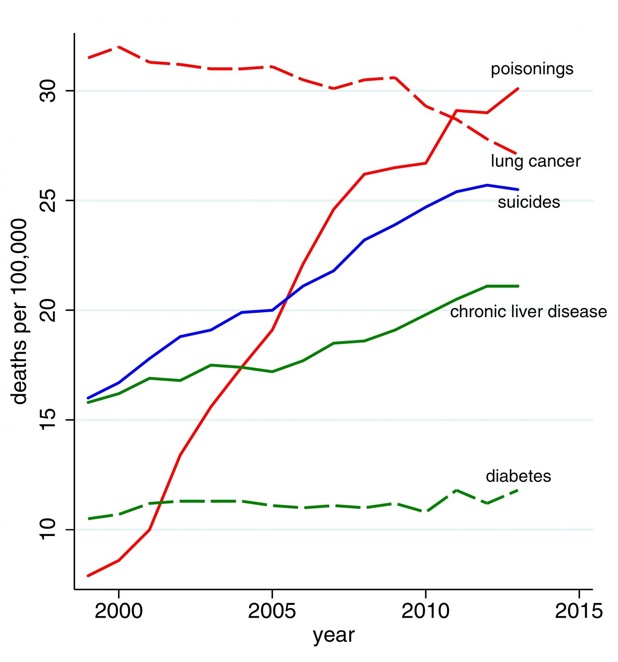

The big culprits are linked to despair, namely “poisoning” which is opioid abuse first and alcoholism second, and suicides. Case and Deaton dug into the underlying statistics, and found distressingly high levels of pain and impaired health in this age group, so pain and physical impairment may well be bigger culprits than economic distress:

And the rise in death rates took place among men and women, in all of the four major regions of the country the authors examined, and obesity rates were not a driving factor.

And unlike chaotic post-Soviet Russia, the US does not have a good excuse as to why this has been happening in a period of supposed growth, and even worse, with no one noticing until now. Yes, there have been warning signs of distress, such as the fact that US life expectancy has stopped rising, that death rates among white women had risen (and over the same time period examined in the Case-Deaton study), and that the US is alone among developed countries in having an increasing maternal mortality rate. And even though the chattering classes may not have been aware of the rise in the death rate of whites, it had been troubling researchers for some time.

Now to the current post. The Journal describes an epidemic of early deaths, with drug overdoses, suicides, accidents (some of which could have been suicides) and gun deaths. The article fingers the lockdowns and remote schooling as a major cause, but ignores the other effects of Covid on mental health, like increased parental anxiety, particularly about what might happen to their job; coping with lockdown shortages (toilet paper, baby formula, some medications and as I recall, even pet food); concern about getting sick; worries about Covid-afflicted relatives, particularly the elderly; grieving for the dead, and potentially cognitive and mood effects from getting Covid, particularly long Covid. Similarly, there’s no mention about angst about the future of the planet, which not surprisingly hang heavy on many young people.

And it predictably fails to mention a big driver of deteriorating social health indicators: high levels of inequality. As we’ve written from the inception of this site, unequal societies are unhappy and unhealthy societies. High levels of inequality exact a longevity cost, even among the rich.

But even with those shortcomings, the Journal article gives a sense of how many young people in the US are showing signs of mental illness and even when they are getting help, are also taking matters into their own hands. From the Journal account:

Between 2019 and 2020, the overall mortality rate for ages 1 to 19 rose by 10.7%, and increased by an additional 8.3% the following year, according to an analysis of federal death statistics led by Steven Woolf, director emeritus of the Center on Society and Health at Virginia Commonwealth University, published in JAMA in March. That’s the highest increase for two consecutive years in the half-century that the government has publicly tracked such figures, according to Woolf’s analysis.

Other developed countries including the United Kingdom, Germany, Canada and Norway also saw a rise in some death counts among young people during that time, though the upticks were often concentrated in narrow age groups or one gender, according to global death counts provided by Christopher J.L. Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington.

The U.S. is the only place among peer nations where firearms are the No. 1 cause of death in young people.

Suicides among Americans age 10 to 19 began increasing in 2007, while homicide rates for that age group started climbing in 2013, according to the research in JAMA by Woolf and co-authors Elizabeth Wolf of Virginia Commonwealth and Frederick Rivara of the University of Washington.

The increases in suicides and homicides among young people went largely unnoticed at first because overall child and adolescent mortality rates still declined most years…

When the pandemic started, deaths of young people due to suicide and homicide climbed higher. Deaths caused by drug overdoses and transportation fatalities—mainly motor-vehicle accidents—rose significantly, too.

Covid, which surged to America’s No. 3 cause of death during the pandemic, accounted for just one-tenth of the rise in mortality among young people in 2020, and one-fifth of it in 2021, according to the research led by Woolf, which uses data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The article presents tragic vignettes: a 11 year old boy, formerly happy and active, who became morose and anxious when deprived of sports and structure. His parents found he was taking marijuana, and got him on anti-depression medication and starting controlling his social media use. When he was staring the school year at 14, he seemed to have turned the corner. But his mother found him dead of a fentanyl overdose one morning.

The pandemic appears to have poured gas on a mental health crisis among the young. Back to the Journal:

Older children and teenagers, ages 10 to 19, accounted for most of the increase in death rates for young people…

Physicians and public-health researchers say that school closures, canceled sports and youth activities and limitations on in-person socializing all worsened a burgeoning mental-health epidemic among young people in the U.S. Social media, they say, has helped fuel it by replacing successful relationships with a craving for online social attention that leaves young people unfulfilled, and exposes them to sites that glamorize unhealthy behaviors such as eating disorders and cutting themselves.

Demand for psychiatric services, counseling and other behavioral health supports far outstripped supply, leaving young patients to turn to emergency departments that were strained by the crush of Covid.

And guns play a significant role:

In 2020, life expectancy fell 1.8 years, the largest decline since at least World War II, not just because of Covid but also because of increased mortality from unintentional injuries, including drug overdoses, as well as homicides.

Researchers point to the fact that gun ownership increased during the pandemic, and that high-profile acts of police violence, including the murder of George Floyd, heightened distrust of law enforcement. That prompted some people to resort to deadly forms of “street justice” instead of calling the police, said Daniel Webster, a public-health professor at Johns Hopkins University who researches gun violence and prevention.

Bear in mind that more still die from gun suicide than gun homicide.

Driving deaths were also up despite a drop in miles driven. Researchers attributed that to driving while impaired, distracted by devices, and fewer cars leading to more dangerous habits.

The article poses no solutions save hinting that more access to mental health services could help. Consistent, with that, it’s distressing to see the sense of resignation, as if this is just another part of the new normal that we have to accept.