Yves here. Americans have a bad case of amnesia. Many of us don’t realize that 100 years ago, in cities, milk and ice were delivered by horse cart, with the beasties knowing where and when to start and stop on their routes. My father (who grew up on Long Island) hated visiting Manhattan during his depression childhood due to the manure stench.

One small connection I have to this past was that Orr’s Island, Maine, next to Bailey Island in Casco Bay, had an ice pond whose ice was sold along the East Coast. They were apparently able to store it and keep it from melting (much) well past the winter months. Nearby Brunswick had a much larger ice pond, Coffin’s Pond, that area residents are trying to preserve it for wildlife and recreation.

This photo is from a 2014 Boston Globe story on the subject of this article, ice king Frederick Tudor, and shows a 1925 ice pond in Maine:

By Michael Svoboda, Ph.D., the Yale Climate Connections books editor. He is a professor in the University Writing Program at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C., where he has taught since 2005. Before completing his interdisciplinary Ph.D. at Penn State in 2002, Michael was the majority owner and senior manager of Svoboda’s Books, an independent bookstore that served Penn State’s University Park campus from 1983 to 2000. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

During a broiling heat wave in the summer of 2018, Amy Brady was visiting relatives in Topeka, Kansas, when the overburdened power grid failed. Miserable inside the sweltering house, the family decamped to a nearby filling station, operating on a gas-powered generator, for the cool air and the iced drinks.

At the time, Brady was the editor-in-chief of the Chicago Review of Books, for which she curated Burning Worlds, a monthly newsletter on fiction and poetry about climate change. One could easily imagine something like her family’s flight to cool appearing in the early pages of a cli-fi novel whose author she had interviewed.

Thinking about ice in a climate-changed future led Brady to wonder about its past. How had ice become so dependably entwined with our daily lives?

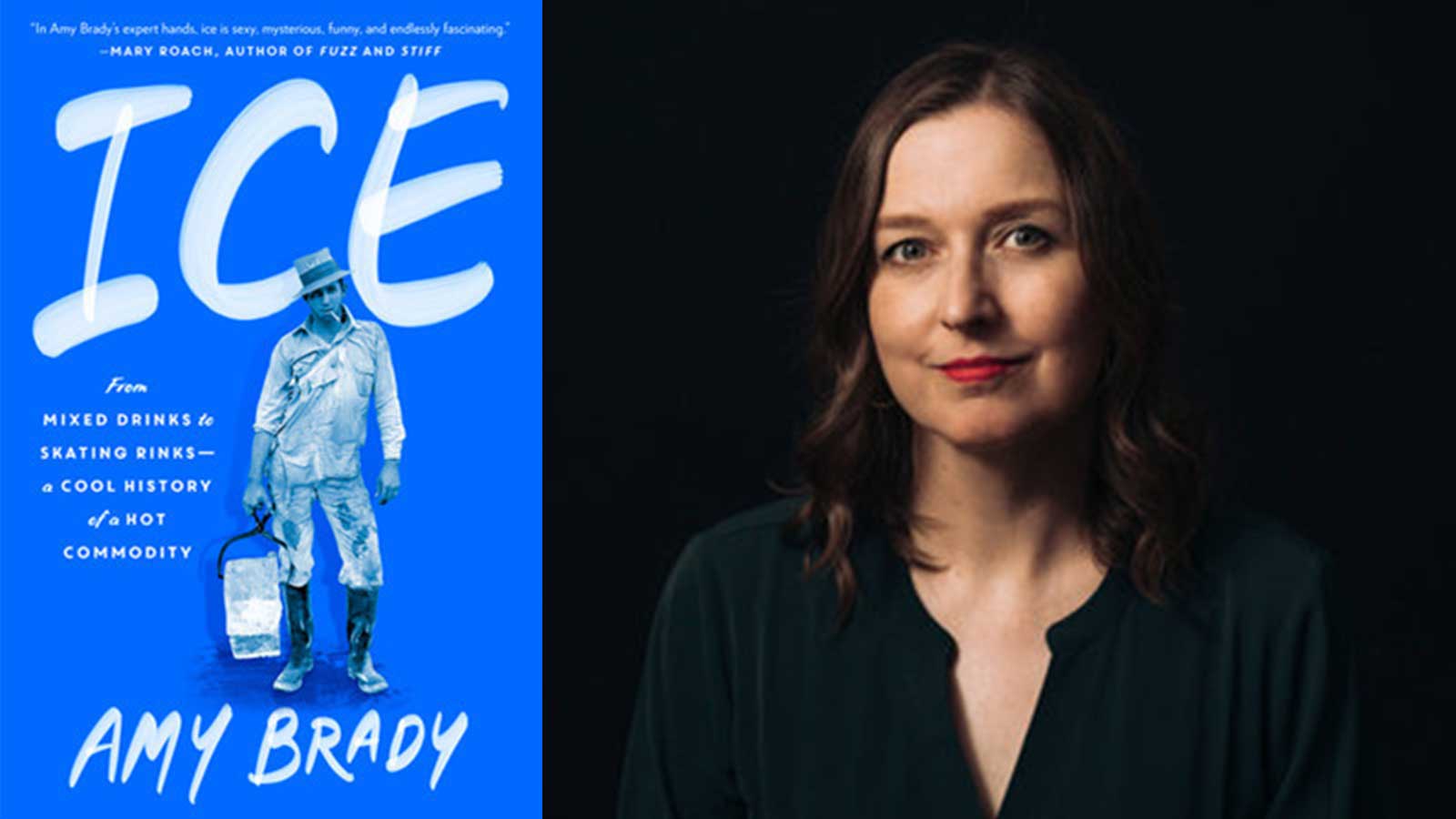

Now the executive director of the esteemed literary and environmental magazine Orion, Amy Brady has just published a book-length answer to her question — “Ice: From Mixed Drinks to Skating Rinks, a Cool History of a Hot Commodity” (G.P. Putnam & Sons).

And because from April 7, 2017, to March 11, 2021, Amy Brady had graciously granted Yale Climate Connections permission to republish her interviews with 48 novelists and poets, we are now grateful for the opportunity to publish an interview with her. Turnabout is fair — and fun — play.

This interview, recorded in late May, has been edited for brevity and sequence.

Michael Svoboda: You begin your history by suggesting that the 18th-century world was divided into two subcultures: northern communities that took ice for granted, at least in the winter, and southern communities for which ice was almost entirely unknown. For ice to become a commercial enterprise, you say, both subcultures had to change. And one man started that process. Tell us about Frederic Tudor.

Amy Brady: Frederic Tudor was an eccentric wealthy Bostonian, born just a day after the American Revolution ended, who started a revolution of his own by sparking an appetite for ice. Although he came from a wealthy family, he decided pretty early on that instead of getting a formal education he would try one business scheme after another until one worked out

He ultimately decided that selling ice cut out of his Massachusetts lake was the answer. His peers thought he was a madman. First, because all of them got their ice for free it never occurred to them that people would pay for it. Then there was the question of how you ship it long distances without melting. So he had to come up with solutions for all of that.

And once he got the ice to warmer climates, he realized that he that were two major pitfalls in his thinking. The first was that there were no ice houses there. So his first shipment melted away on the ship. The second was that the people to whom he brought the ice had rarely if ever seen ice before. They didn’t know how to use it. So he had to create a demand for this stuff.

Svoboda: One of the very fun through-lines of your book is the interplay between ice and alcohol. Tell us how the ice trade transformed local and regional drinking cultures.

Brady: Tudor went to Cuba before he tried the southern United States. There, to get the baristas to use ice in their drinks, he initially gave it away for free. “Just see if people like it,” he told them. And of course they did. Once the demand was there, he started selling his ice at an ever-increasing price.

He did the same thing when he landed in New Orleans and created what many people refer to as “the cradle of civilized drinking.”

Svoboda: Fairly quickly, you note, the demand for ice exceeded the “natural” supply. This led to the “blasphemous” invention of artificial ice. Take us through some of the critical moments in that story.

Brady: Well, this goes back to Dr. John Gorrie, who was a doctor from New York who moved to Apalachicola, Florida, a tiny port town off the Gulf Coast of Florida. He went there to fight yellow fever, a disease that ravaged the American southern states every summer.

Keep in mind that doctors didn’t know that the disease was transmitted by mosquitoes. But what Gorrie noticed was that every year, without fail, the disease came with the hot months and receded with the cool months.

Not knowing that this was due to the mosquitoes’ life cycle, he thought it had something to do with the temperature itself. And so he landed on the idea that perhaps he could cure his patients of yellow fever if he could lower their body temperature.

The only way he could think to do that was with ice. But this was Apalachicola, Florida. Any ice that came into the area in the high summer was so expensive that residents called it “white gold.”

Gorrie was not a wealthy man. And so he realized that if he was going to get ice for his patients, he was going to have to figure out how to make it for himself. He had studied various sciences during his schooling, and eventually, he created a prototype for an ice machine that could create a significant amount of ice.

But when he announced his invention to the world, he was met with cries of “blasphemy!” How dare a man try to make ice — only God can. He ended up dying in poverty of the very disease he was trying to cure. In fact, it wasn’t until the Civil War, when access to Northern ice was cut off by the embargoes, that the Southern states said we need to figure out how to get ice. And they ended up buying a blueprint from Europe that was suspiciously close to what Gorrie had created.

Svoboda: So soon we have the means to produce ice anywhere, all year round?

Brady: Yes. Ice-making became a lucrative business, in and of itself, with several competing ice companies. But the widespread availability of ice also gave rise to other industries. Mechanical ice, combined with the railroads, meant that perishable goods, packed in ice, could be transported long distances. And so the breweries scaled up their businesses. The fishing industry took off because folks inland could now eat fish. Thanks to the ice cars, meatpacking became an enormous industry. And of course, all the icy treats like ice cream and sherbets became possible.

Svoboda: And this sets the stage for the popular but risqué figure of the iceman.

Brady: Harvesting ice from frozen lakes or rivers or creating mechanical ice by machine was just the first part of the cold chain. Now the ice companies had to get ice into the homes of consumers. So they hired hundreds of thousands of delivery men. These were the icemen. And they would load the ice into the back of their horse-pulled wagons, and eventually into their motorized vehicles, and they would drive it to the customers’ homes. Then these icemen would take these 50-pound blocks of ice and haul them up into their customers’ homes and put them into their iceboxes.

In researching the history of the iceman, I often came across popular songs written about them — and they were always romantically themed. They were about a young woman — or an older woman — stealing a kiss from the iceman.

Looking into this more, I realized that there was an anxiety about this figure. When you look at the other delivery people of the day — the milkman, the mailman — they left their wares outside. The iceman, however, crossed that forbidden domestic threshold. He went into the house, usually during the day when the husband was away at work, and was alone there with the wife.

And so I think often of that 1930s song [“I’m Gonna Move To The Outskirts of Town”], made popular by Ray Charles in the ‘50s or ‘60s, which ends with “I don’t need no iceman, I’m gonna get you a Frigidaire.”*

Svoboda: In almost every chapter of your book, you tell the stories of people who are usually left out of official histories. One of the stories enhanced by this special effort on your part is the story of ice cream. How do you tell the story of America’s favorite frozen treat?

Brady: My Ph.D. came from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where some really great professors taught me that there’s not just one story. To tell a more inclusive story, and I would say a more accurate story, you need to look beyond the single, overarching narrative that so many of us are taught at a young age.

And so I did. And what that revealed for me, with the story of ice cream in particular, was that it became such a popular dessert in the United States not, as I had often read, because presidents had popularized it. Although, yes, Dolly Madison, the wife of President James Madison, was renowned for her ice cream parties and soirees. But ice cream actually became popular with the masses because of the work of immigrants and Black American entrepreneurs, who learned how to make it, store it, and disseminate it to people who didn’t have a lot of money or who weren’t allowed in the White, wealthy spaces where ice cream had been served. These entrepreneurs created their own ice cream parlors and gardens, up and down the Eastern Seaboard.

Svoboda: You devote an entire section of your book to the intersections between ice and sports. Can you share a few highlights?

Brady: Yes, that was an interesting section to write. And I was really surprised by a number of things I discovered. One is that none of the sports I talk about in the book — ice skating, speed skating, hockey, curling — are played on the same sheet of ice. It’s all very different, by design, because the surface needs to be specially crafted for the sport that’s being played on it.

And then when I dug deeper into the slipperiness of ice, I was surprised to learn that there’s still some debate over what makes ice slippery. What’s weird about curling, in particular, is that the stone actually curves in the direction in which you spin it rather than the counter direction, which is how every other object on Earth works. And scientists really don’t know why that is. Ice continues to elude us.

Svoboda: In your final chapters, you remind readers that it takes energy to make things cold in a hot environment. Chilling contributes to the global warming for which it is also — through iced drinks and air conditioning — one of the most effective balms. Can we keep this circle from becoming vicious?

Brady: Well, let’s hope we can. Refrigeration and air conditioning contribute 10% of the world’s greenhouse gases. But there are some things to consider. The first is that the refrigerators we have today are much more energy efficient. That’s a combination of better technology and state and federal standards, like EnergyStar, that incentivize both consumers and manufacturers to do better. Second, there are fascinating new technologies that are being experimented with now. It’s a matter of making sure these technologies work and then scaling them up on a massive scale.

What exploring the history of ice taught me is that we are a nation that can change very quickly — because of a technological innovation or a marketing scheme. The adoption of refrigerators and freezers happened almost as quickly as the adoption of television sets — which is to say in less than 10 years. If we are a country that can very quickly change how people think of and consume ice, then just imagine what we can do if we want to save it.

Svoboda: I’d like to close by asking you to place your work in the context of the many novels you discussed in your Burning Worlds columns. In “Ice,” you seem more optimistic about our future under climate change than most of the authors you’ve interviewed. How should readers understand that difference?

Brady: I so appreciate that question. When I started the Burning Worlds column, much of the fiction that I talked to writers about was pretty dire. It was pessimistic. It was apocalyptic. But in more recent years, the pendulum has started to swing the other way. I’m thinking of recent books by Lydia Millet, Amitav Ghosh, and many others. They’re not Pollyannish; they get to the heart of why climate change exists, and they don’t shy away from terrible consequences of it. But they also suggest that there is hope for the future. My book is emotionally informed by that later work. We’ve seen so much change, just in the last decade. At the very least, people are now talking about it in a way they weren’t 10 years ago. And the first step to solving a problem is being aware that it exists.

*Editor’s note: This sentence was edited to reflect the correct lyric.