By Sara Abrahamsson, Postdoctoral researcher at Norwegian Institute Of Public Health, Aline Bütikofer , Professor at Norwegian School of Economics (NHH), and Krzysztof Karbownik, Assistant Professor, Department of Economics at Emory University. Originally published at VoxEU.

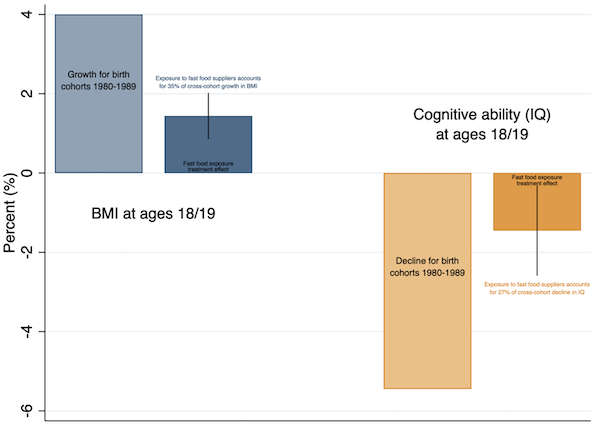

Around the world, obesity during childhood and adolescence is on the rise. Its causes are complex and multifaceted but environmental factors are often named as a major culprit, with the increased supply of fast food garnering particular press and policy attention in recent decades. Using Norwegian registry data, this column documents that the increased supply of fast food restaurants could be responsible for as much as 35% of the increase in BMI and 27% of the decline in cognitive ability observed across cohorts born during the 1980s. Policies reducing the obesogenic environment could thus be an effective way to reverse the trends observed in recent decades.

Elevated body mass index (BMI) is one of the leading causes of preventable morbidity and mortality in Western countries. It is associated not only with severe health outcomes such as asthma, diabetes, cardiovascular problems, or cancer (WHO 2016), but also with higher health care costs (Cawley and Meyerhofer 2012) and adverse economic outcomes such as lower wages in adulthood (Lundborg et al. 2014). Although various actions are being taken to reduce and reverse the ‘obesity epidemic’, it is predicted that by 2035 over half of the world’s population will be overweight or obese, including one in five children and adolescents. The annual economic cost of these trends is expected to reach $4.32 trillion in 2035, or almost 3% of global GDP (World Obesity Federation 2023). For reference, this is similar to the global impact of Covid-19 in 2020, the pandemic’s worst year (World Bank 2022).

Several countries have tried to take action to curb the upward trend by imposing taxes on sodas (Dubois et al. 2020), changing advertisement practices (Dubois et al. 2018), posting the caloric content of food items (Aranda et al. 2021), or outright banning fast food outlets (Brown et al. 2022) or the sale of junk food in schools (Leonard 2017). The latter set of far-reaching and controversial policies have some support in the medical community. For example, the Royal College of Pediatrics and Childhood Health in the UK advocates for banning fast food operations within 400 metres of schools (RCPCH 2018), the American Medical Association calls for eliminating junk food in hospitals (American Medical Association 2017), while the Australian Medical Association suggests banning junk food ads targeted at children (Australian Medical Association 2018). A call for policy action is further motivated by existing, albeit far from universal, evidence that easier access to fast food increases BMI (Cawley 2015). For example, Davis and Carpenter (2009) and Currie et al. (2010) demonstrate that teenagers attending a school near to a fast food restaurant have elevated BMI and other measures of excess weight. In contrast, Howard et al. (2011) and Asirvatham et al. (2019) find no such relationship. Other papers examine exposure at the place of residence, with results likewise ranging from increases in BMI (Elbel et al. 2020) to no effects (Dolton and Tafesse 2022).

Fast Food Restaurants in Norway

In a recent paper (Abrahamsson et al. 2023), we ask whether the increased supply of fast food leads to worse health and cognitive outcomes among young adult males in Norway. We focus on exposure in tightly defined places of residence during the childhood and adolescence periods. Administrative data allow us to link an individual’s location with the location and openings of fast food restaurants. Our proxy for health is BMI, while cognition is assessed using standardised IQ tests. Both are measured at the age of 18/19 for a universe of Norwegian males via mandatory conscription.

Our empirical approach exploits quasi-random variation in changes in the supply of fast food outlets. Thus, we compare the outcomes of individuals residing in narrow geographic locations in Norway where a restaurant has and has not been opened, and before versus after its establishment. Our results should be interpreted as effects of facilitating easier access to, rather than consumption of, fast food. Although not all individuals in these locations consumed fast food meals, prior literature suggests that increased supply leads to higher consumption (Moore et al. 2009). Furthermore, approximately 60% of Norwegian 15- to 24-year-olds reported eating “American fast food” at least once a month in the early 2000s (Bugge Bahr 2023).

The first (Western) fast food restaurants opened in Norway’s capital, Oslo, in the late 1970s and marked the arrival of a completely new food concept. Since then, the number of these suppliers has expanded dramatically, and by 2007 (the end of our sample), there were almost 800 of them (Figure 1, Panel A). In parallel, cohorts born during the 1980s – the first children and adolescents to grow up in an environment with a rapidly increasing supply of fast food – experienced 4% increases in BMI and 5% declines in cognitive ability (Figure, Panel B). Outcomes at the upper tail of the weight distribution escalated even more, with overweight rates rising by 30% and obesity rates rising by 75%.

Figure 1 Trends in the number of fast food restaurants, BMI, and cognitive ability

Note: Panel A presents number of fast food restaurants in Norway between 1980 and 2007. Panel B presents average BMI (left y-axis) and average cognitive ability score (right y-axis) measured at ages 18/19 for birth cohorts between 1980 and 1989.

Higher BMI and Worse Cognitive Outcomes from Fast Food Exposure

To verify the aforementioned visual time series correlations, we use a regression analysis. We find that growing up in a neighbourhood that has a fast food restaurant increases BMI and the likelihood of being overweight in young adult males. We calculate that for an average exposure in our data, which is about seven years between birth and age 18/19 when the outcomes are measured, individual BMI increases by 1.4% which is about 35% of the growth in mean BMI between the first and the last cohort considered (Figure 2). Additionally, we find increases of 1.6% and 2.9% per year of exposure to a fast food establishment when considering overweight and obesity likelihoods, respectively.

We document parallel deterioration in cognitive ability. A point estimate suggests 0.56% of a standard deviation (SD) decline per year of exposure, which, given the aforementioned average exposure in the data, could explain about 27% of the cross-cohort downswing. The IQ finding is unaffected by controlling for BMI, which suggests that it is largely orthogonal (and plausibly additive) to any negative health effects.

Across both health and cognitive outcomes, we find surprisingly little heterogeneity. The fast food effects do not appear to be mediated by individual health at birth, paternal BMI, or household socioeconomic status. We do note, however, that cognitive ability is only affected by early life exposure at ages 0-12. In this case, we further find that the effect is halved in families where the father has at least an academic high school degree.

Our findings are robust. Point estimates and statistical significance are not materially affected by the choice of econometric specifications, estimation sample, definition of treatment distance, or transformations of the dependent variable. We also document parallel trends prior to restaurant openings. These tests mitigate concerns that selection or spurious trends are driving our results.

Figure 2 Main results

Note: This figure presents average growth of BMI and decline of cognitive ability between birth cohort 1980 (first birth cohort in our data) and 1989 (last birth cohort in our data) as well as average treatment effects of exposure to fast food restaurants. Navy bars present results for BMI while orange bars present results for IQ scores. Black vertical spikes present 95% confidence intervals based on standard errors clustered at municipality of birth level.

Implications for Policy Response

We show that adverse fast food supply effects could arise even in a Nordic country with a relatively healthy population, high per capita income, high levels of education and nutritional literacy, and universal free healthcare. This is concerning given that many studies on weight reduction find small or no effects and that the penetration of unhealthy food providers keeps increasing. Our findings for the cognitive outcomes increase the stakes of a potential lack of countermeasures even more. They could also help in understanding the decline in cognitive ability in multiple countries in recent decades (Dutton et al. 2016). Finally, the relative homogeneity of our findings suggests that any interventions or campaigns should target a broad population rather than specific groups – for example, those with a history of obesity in their families (Griffith 2022). Without action, the prediction that within a decade more than 30% of the Norwegian adult male population will be obese (Lobstein et al. 2022) could indeed materialise.

References available at the original.