By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

Readers who have been following our HICPAC journey (CDC’s Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee) will be aware that HICPAC is holding a meeting on August 22 that could possibly lower infection control standards, especially by eliminating any possibility of universal masking with N95 respirators in hospital settings. (HICPAC members are all affiliated with hospitals or other medical facilities, and are thus conflicted about recommending against universal masking in hospital facilities when their own institutions have already done so.) Readers will also be aware that one reason HICPAC downgraded protections against airborne MRSA in hospitals was budgetary (and not patient safety). Finally, readers will be aware that HICPAC is out of compliance with both the letter and the spirit of the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA), the law that governs Federal advisory committees.

In this post, I will let fly at what I hope is the soft underbelly of the beast: a draft document entitled “Isolation Precautions Guideline Workgroup,” acquired by HealthWatch USA after HICPAC’s previous meeting on June 8, not available on the CDC’s HICPAC page, despite its status as a “work group” document. From Slide 2 of that document:

I write “Slide” 2 because, in yet another sign of our society’s operational incapability, HICPAC is making decisions affecting the health and lives of millions not only based on a draft, but a draft PowerPoint presentation, bullet points and all. That said, from the General Services Administration (GSA), the FACA guidance on “deliberative material”:

The Federal Advisory Committee Act requires advisory committees to make available for public inspection written advisory committee documents, including pre-decisional materials such as drafts, working papers and studies.

In my view, HICPAC’s Designated Federal Officer, Michael Bell, M.D., should use his authority to either postpone or immediately adjourn the August 22 meeting, reconvening when HICPAC is fully compliant with FACA.

Be that is it may, in this post I will look at one section of the “Isolation Precautions” draft: “The Evidence Review” (starting on Slide 26), which poses the following question:

For healthcare personnel caring for patients with respiratory infections, what is the effectiveness of medical/surgical masks compared with N95 respirators in preventing infection?

The “Evidence Review” answers to the question it poses — spoiler: “No,” but they’re wrong — in the form of aggregated tables (“snapshots”) that characterize many mask studies. First, I’ll examine the methods by which these tables were created. Then, I will disaggregate the tables, which will yield some interesting results. (It is perhaps at this point needless to say that both the methods and the tables are positively replete with FACA violations, and in fact, at critical points, opaque.) Both parts are quite detailed. This post will be long, but the things that satisfy only come real slow.

Before I begin, a note on the scope of this post: The “Evidence Review” also raises the equation of “Adverse Effects” from masking — here one remembers WHO mask-opposing fossil maven John Conly weighing the harms of SARS-CoV-2 infection against the harms of acne — but they are out of scope for this post. Further, even though the “H” in HICPAC stands for “Healthcare,” not “Hospital,” I will mentally prioritize hospitals over other institutions; partly because I wish to drive the project of universal masking in hospitals forward, but also as a sop to the interests of HICPAC members, the vast majority of whom are affiliated with these institutions.

HICPAC “Evidence Review” Methods (with FACA Violations)

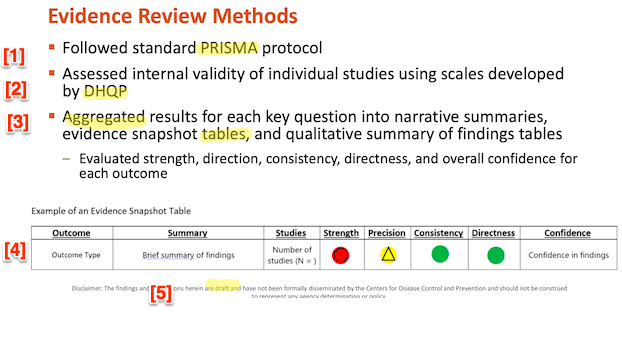

Slide 28 gives an overview of the methods used for the “Evidence Review”:

First, I will look at PRISMA [1], then DHQP [2]. I will look at the aggregated tables [3] in the next section, disaggregating the so-called “evidence snapshots.” Note once more the boilerplate at [5]: Whether or not “the findings and conclusions herein are draft” and “have not been formally disseminated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and should not be construed to represent any agency determination or policy,” that this does not remove HICPAC’s duty under FACA to make this draft available to the public. (I’ve gotta say that the red, yellow, and green icons [4] remind me powerfully of the color-coded “Homeland Security Advisory System” under President George W. Bush. Red is bad!)

First, PRISMA. PRISMA (“Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses”) is sponsored by the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, the University of Oxford, and Monash University. PRISMA’s scope:

PRISMA is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. PRISMA primarily focuses on the reporting of reviews evaluating the effects of interventions, but can also be used as a basis for reporting systematic reviews with objectives other than evaluating interventions (e.g. evaluating aetiology, prevalence, diagnosis or prognosis).

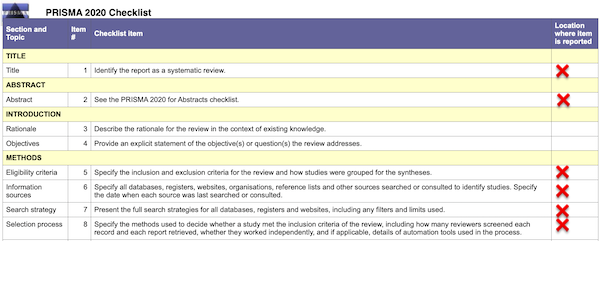

Well and good. PRISMA also provides a handy checklist for entities that wish to conform to its guidelines. Here, in relevant part, is the checklist; it’s a literal checklist; I have helpfully added a red “❌” in the right hand column for every item that is not provided by the HICPAC “Evidence Review”:

In detail by item # (column 2):

(1): The “Evidence Review” is not identified as a “Systematic Review.” That phrase appears nowhere in the document. “Evidence Review” is not an acceptable as a title under PRISMA.2

(2): There is no abstract.

(5): The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies are not specified. (The Appendix contains all the mask studies listed in the “References” formatted as a table. I have made all links clickable, something HICPAC unaccountably failed to do.)

(6): No information sources are specified. No dates for search or consultation are specified.

(7): No “full” search strategy is presented.

(8): No selection strategy is specified.

In short, we are looking at a vague gesture in PRISMA’s direction, not “standard PRISMA protocol,” as Slide 28 and DHQP would have it. We are not looking at the “minimum set” of items necessary to follow PRISMA guidelines. If a checklist with the missing items does not exist, then HICPAC is derelict in its duties. If it does exist, even in draft form, then HICPAC is in gross violation of FACA by not making them public. So far, we are looking mere formalism.

Second, DHQP (CDC’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion). From its page:

The mission of the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion (DHQP) is to protect patients; protect healthcare personnel; and promote safety, quality, and value in both national and international healthcare delivery systems

And:

In carrying out its mission, DHQP… promotes the nationwide implementation of Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) recommendations and other evidence-based interventions to prevent HAIs, antibiotic resistance, and related adverse events or medical errors among patients and healthcare personnel.1

Well and good. But where, exactly, are these “scales” (Slide 28, above), developed by DHQP, by which the “internal validity of individual studies” aggregated in the putative “Evidence Review” is assessed? The scales are not incorporated anywhere in the draft document, not even by reference. Since the author of the “Evidence Review,” “Erin Stone, MPH” is the “Lead, Office of Guidelines and Evidence Review (OGER)” for DHQP, one presumes the scales exist and have been applied to the studies. Once again, if these deliverables do not exist, HICPAC is derelict in its duties. If they do, even in draft form, HICPAC is in gross violation of FACA.

Having established that the “Evidence Review” does not conform to PRISMA, and having established that if indeed there are “scales” by which the aggregated studies were evaluated, we the public have no idea what they may be or where they are to be found — not on the HICPAC page at CDC! — let us turn to the “snapshot tables” and disaggregate them.

Quality of HICPAC Evidence Review on Masks

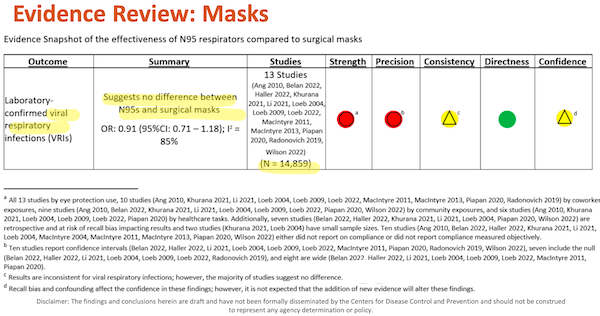

There are two “snapshot tables” that aggregate the individual studies (recall that I have ruled “Adverse Events” out of scope). Let us look at each in turn. Slide 31:

I’ve helpfully highlighted major points in yellow. Under “Outcome,” we see that this table is directly relevant to Covid, which is airborne. Under “Summary” we see how DHQP, in the person of Erin Stone, has answered the major question posed by the “Evidence Review.” Under Studies, we see “N”, presumably the aggregated N of all the studies. (I highlight this only because it seems odd to view participants across studies as fungible; perhaps statistics or epidemiology mavens can clarify.)

Now let’s look at the footnotes to the table, (d) – (a), because as any lawyer knows, footnotes are where the fun is to be had, and as Edward Tufte knows, the detail is buried at the lowest level.

(d) “Recall bias and confounding affect the confidence of these findings; however, it is not expected that the addition of new evidence will alter these findings.” First, “affect the confidence” how much? Apparently, this is entirely a subjective matter, much like “confidence” in the stock market, and not a metric at all. So we don’t need to worry very unduly about statistical detail, if DHQP doesn’t. Next, note the institutional voice in “it is not expected.” “Not expected” by whom and why? Once again, FACA would like to know, especially since HICPAC is about to decide not to wait for “new evidence” (that is, additional studies, perhaps like this one) before making a decision affecting the life and health of millions.

(c) “Results are inconsistent for viral respiratory infections; however, the majority of studies suggest no difference.” First, “inconsistent” why? The Covid conscious would like to know. Second, is science really performed by majority vote? MR SUBLIMINAL Pause for discussion of paradigm shifts and “one funeral at a time”.

(a) – (b) Metrics for “Strength” and “Precision” are disaggregated in Table I below.

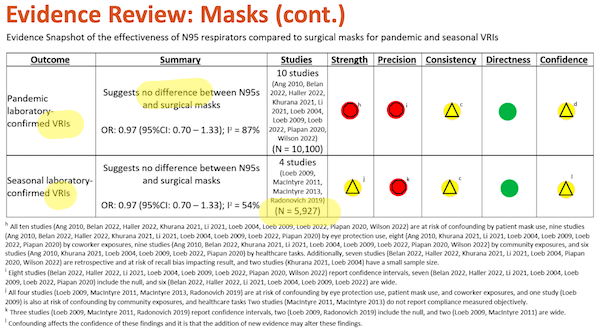

Slide 32:

Once again, I have highlighted major points in yellow. Under “Outcome,” we see “VRI” (Viral Respiratory Infection, which is good, since SARS-CoV-2 is a virus). For comments on “Summary” and “Studies, see Slide 31, above.

And to the footnotes, again starting from the bottom:

(l) “Confounding affects the confidence in these findings and it is that the addition of new evidence may alter these findings.” First, “and it is that” shows that this footnote, not being grammatical is meaningless; read it again if you disagree. Second, “may alter these findings” why? Who says? And why does does Slide 31, footnote (d) “not expect” new evidence, and this footnote contemplate it?

(h) – (k) Metrics for “Strength” and “Precision” are disaggregated in Table I below.

Now let us disaggregate. Table I lists every study in the “snapshots” in Slides 31 and 32. My goal in doing this is to see if the studies differ significantly in any way, such that an aggregation would conceal rather than reveal. (Recall from our examination of PRISMA that we do not know the inclusion or exclusion criteria for the studies, the information sources or dates of search, the search strategy, or the selection strategy.) First, I’ll present the disaggregation, then explain it, then look at what the aggregation may have concealed, that disaggregation reveals.

Table I: Disaggregating HICPAC’s “Evidence Review” on Masking

| Strength | Precision | ||||||||||||

| Confounders | |||||||||||||

| # | Short Name | Study Type | Demerits | Eye | Coworkers | Pnt. Mask | Commun. | Tasks | Retro. | Small | Compl. | CI | Null |

| 26 | Macintyre 2011 | RCT | 2 | ` | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ||||||

| 27 | Macintyre 2014 | RCT | 2 | ❌ | ❌ (2004) | ❌ | ❌ | ||||||

| 39 | Radonovich 2019 | RCT | 2 | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ||||||

| 28 | Macintyre 2013 | RCT | 3 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | |||||

| 14 | Haller 2022 | Cohort | 4 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ||||

| 7 | Belan 2022 | Matched case-control | 5 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | |||

| 24 | Loeb 2009 | Randomized Trial | 5 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | |||

| 23 | Loeb 2022 | Randomized Trial | 5 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | |||

| 21 | Li 2021 | Cohort | 6 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ||

| 46 | Wilson 2022 | Cross-sectional | 6 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | |||

| 36 | Piapan 2020 | Observational | 7 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | |

| 5 | Ang 2010 | Observational | 8 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ||

| 25 | Loeb 2004 | Cohort | 8 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| 17 | Khurana 2021 | Observational | 10 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

LEGEND

Except for “#”, column headings are derived from Slide 31:

#: Cross-reference to “#” column in Table II, in the Appendix.

Confounders: “Eye,” Eye Protection; “Co-Workers,” Co-Worker Exposures; “Pnt. Mask,” Patient Masking; “Tasks,” Healthcare Tasks.

Retro.: Retrospective, at risk of recall bias.

Compl.: Either did not report on compliance, or did not measure objectively.

CI: Confidence Interval

Null: Includes the null hypothesis.

Reading horizontally, you can see that every row represents a study. In each row, there are columns for all the confounders and other negative factors (“Retro.”, “Small”) described in footnotes (a)-(b) in Slide 31, and footnotes (h)-(k) in Slide 32. Wherever a “snapshot” footnote categorized a study with a negative factor, I put a red “x” in that factor’s column. For each study, I summed the red “x”‘s, and put that value in the Demerits column. I then sorted the table on Demerits. As you can see, studies 26 – 39 have the fewest demerits — hence are the best studies, for this definition of “best.” Study 17, at the bottom, with demerits across the board, is the worst.

What does our disaggregation reveal? Let’s quote from the “best” studies, which I have highlighted. (It may or may not be significant that four out of the top five are [genuflects] RCTs.) There are three Macintyres, so let’s quote from them first:

First, #26, Macintyre 2011, “A cluster randomized clinical trial comparing fit‐tested and non‐fit‐tested N95 respirators to medical masks to prevent respiratory virus infection in health care workers.” From the Interpretation:

Rates of infection in the medical mask group were double that in the N95 group. A benefit of respirators is suggested but would need to be confirmed by a larger trial, as this study may have been underpowered.

Note that the “Evidence Review” does not characterize Macintyre 2011 as “small,” so perhaps Macintyre is being overly punctilious (they make a number of other qualifications, as they should, in the discussion). N = 1441 HCWs in 15 Beijing hospitals. An interesting sidelight on adverse events:

Interestingly, this population of Chinese HCWs reported overall similar rates of discomfort with masks as parents in our household study, 10 with higher rates in the N95 group, but it did not affect their adherence with mask/respirator wearing. This suggests that discomfort is not the primary driver of adherence, and rather, cultural acceptability and other behavioural factors may be the main reason for non‐adherence. The past experience of Beijing health workers with SARS may also be a factor in the high adherence. This level of adherence may not translate to Western cultural contexts in a normal winter season, especially for N95 respirators; however, adherence can change with perception of risk.

Second, #27, Macintyre 2014, “Efficacy of face masks and respirators in preventing upper respiratory tract bacterial colonization and co-infection in hospital healthcare workers“:

N95 respirators were significantly protective against bacterial colonization, co-colonization and viral-bacterial co-infection. We showed that dual respiratory virus or bacterial-viral co-infections can be reduced by the use of N95 respirators. This study has occupational health and safety implications for health workers.

And:

We have previously shown that N95 respirators protect against clinical respiratory illness (MacIntyre et al., 2011, Macintyre et al., 2013). N95 respirators, but not medical masks, were significantly protective against bacterial colonization, co-colonization, viral-bacterial co-infection and dual virus infection in HCWs. We also showed a statistically significant decrease in rates of bacterial respiratory colonization with increasing levels of respiratory protection. The lowest rates were in the N95 group, followed by the medical mask group, and the highest rates were in HCWs who did not wear a mask. Although the clinical significance of this finding is unknown in terms of the implications for HCWs, we have shown that such colonization can be prevented by the use of N95 respirators.

Third, #28, Macintyre 2019, “A Randomized Clinical Trial of Three Options for N95 Respirators and Medical Masks in Health Workers“:

Continuous use of N95 respirators was more efficacious against CRI than intermittent use of N95 or medical masks. Most policies for HCWs recommend use of medical masks alone or targeted N95 respirator use. Continuous use of N95s resulted in significantly lower rates of bacterial colonization, a novel finding that points to more research on the clinical significance of bacterial infection in symptomatic HCWs. This study provides further data to inform occupational policy options for HCWs.

And:

In a setting of high occupational risk for HCWs, the key observation of this study is significant protective efficacy against clinical infection of continuous use of N95 respirators compared with targeted use and medical masks, despite significantly poorer adherence in the continuous use N95 arm. These results add weight to the findings of our previous study (16) that showed that N95 respirators have superior clinical efficacy to medical masks, despite the greater discomfort and lower adherence associated with respirator use. We also showed that the benefit of N95 respirators persisted after adjusting for the potential confounding by influenza vaccination and hand washing.

(An interesting discussion follows on why a control arm with no masking isn’t ethical, at least in China.)

And now, to be fair, fourth, #39, Radonovich 2019, “N95 Respirators vs Medical Masks for Preventing Influenza Among Health Care Personnel: A Randomized Clinical Trial“:

Among outpatient health care personnel, N95 respirators vs medical masks as worn by participants in this trial resulted in no significant difference in the incidence of laboratory-confirmed influenza.

And:

In this pragmatic, cluster randomized trial that involved multiple outpatient sites at 7 health care delivery systems across a wide geographic area over 4 seasons of peak viral respiratory illness, there was no significant difference between the effectiveness of N95 respirators and medical masks in preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza among participants routinely exposed to respiratory illnesses in the workplace.

Finally, fifth, #14 Haller 2022, “Impact of respirator versus surgical masks on SARS-CoV-2 acquisition in healthcare workers: a prospective multicentre cohort“:

Respirators compared to surgical masks may convey additional protection from SARS-CoV-2 for HCW with frequent exposure to COVID-19 patients.

And:

This is, to our knowledge, the first prospective multicentre study comparing the effect of respirators and surgical masks regarding protection from SARS-CoV-2.

The overall association between FFP2 use and risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection was marginally not significant. This is probably a reflection of the heterogeneous study population, two thirds of which consisted of HCW with only sporadic (or even no known) COVID-19 exposure. However, for HCW with frequent exposure, we found a significant protective effect associated with FFP2 use. Several reports suggest that aerosol transmission is indeed a non-negligible mode of SARS-CoV-2 transmission and that respirators may provide additional protection compared to surgical masks. On the other hand, case reports have suggested that surgical masks are equivalent to respirators in protecting HCW from SARS-CoV-2 infection/ These supposedly contradictory findings can be reconciled when considering a particular feature of SARS-CoV-2, namely its high overdispersion.

Why the differences between Macintyre 2011, Macintyre 2014, and Macintyre 2019, on the one hand (thumbs up to respirators, thumbs down to “Baggy Blues” and Radonovich 2019 (“makes no difference”)? I would speculate that all the Macintyre studies were for a single season in-hospital, and Radonovich was over several years for outpatient sites, so for Radonovich the community was a massive confounder. Why the difference between Radonovich 2019 and Haller 2022, which includes hospitals and outpatient clinics (rehabilitation, psychiatry)? I can’t speculate, although Radonovich was for influenza, and Haller for flu.

Conclusion

A few thoughts:

1. I think any reader or citizen not inside the cozy club of HICPAC and DHQP would and of right ought to be frustrated and outraged by the lack of transparency in the process of making mask policy. FACA was designed, and GSA provided guidance, exactly so that the public could be fully informed of the scientific thinking behind HICPAC guidance. And yet, as I show in case after case, information that FACA mandates be made “available for public inspection” (including drafts) is outright missing, whether from the “Isolation Precautions Guideline Workgroup” document, or from the CDC site. How is a dull normal like me supposed to prepare for the August 22 HICPAC meetings? Are we simply to take CDC deliverables on faith? How has that been working out so far?

2. Readers and citizens, if not already outraged by missing information and HICPAC’s failure to abide by the plain meaning of FACA, should also be outraged by HICPAC’s mischaracterization of the material that we can see. DHQP characterizes its so-called “Evidence Review” as following PRISMA “standard protocol.” As I show, it does not, down to the very title. Again, if there’s a full, written, formal version of the “Isolation Precautions Guideline Workgroup” parallel to or derived from the slides, it’s a FACA violation not to make it “available for public inspection.” Does it exist? Or a slide deck — is that all there is?

3. I’d very much like to believe that when I disaggregate Slides 31 and 32, and pro-respirator, anti-Baggy Blue studies — to everyone’s utter surprise! — float to the top, that I have committed an error, and that HICPAC and CDC are on the up-and-up, having learned something from CDC’s initial debacle on mask policy, and its losing tooth-and-nail battle against the science and engineering of airborne transmission. Recall, however, our examination of PRISMA: We do not know the inclusion or exclusion criteria for the studies, the information sources or dates of search, the search strategy, or the selection strategy. CDC has form. A hermeneutic of suspicion is fully justified.

4. Grant, for a moment, that all the studies are bad and we don’t know anything. Doesn’t it make sense to err on the side of patient welfare, rather than Hospital Infection Control’s line item for PPE?

5. “But muh statistics!” What statistics? I don’t see any statistics. I see colored icons. See discussion of PRISMA and DHQP, above.

6. Given that “everything is like CalPERS,” I wonder if HICPAC has simply delegated too much authority to staff, and is simply rubberstamping DHQP’s work product, not least because its implicit conclusions conform to their own priors.

NOTES

1 DHQP “promotes” HICPAC recommendations, HICPAC’s charter says that one of HICPAC’s “duties” is to provide “guidance” to DHQP, and yet here we have DHQP providing an “Evidence Review” to HICPAC. It all seems rather reflexive and circular.

2 I’m not being overly fastidious. From the BMJ, “PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews“:

Item 1. Identify the report as a systematic review

Explanation: Inclusion of “systematic review” in the title facilitates identification by potential users (patients, healthcare providers, policy makers, etc) and appropriate indexing in databases. Terms such as “review,” “literature review,” “evidence synthesis,” or “knowledge synthesis” are not recommended because they do not distinguish systematic and non-systematic approaches. We also discourage using the terms “systematic review” and “meta-analysis” interchangeably because a systematic review refers to the entire set of processes used to identify, select, and synthesise evidence, whereas meta-analysis refers only to the statistical synthesis. Furthermore, a meta-analysis can be done outside the context of a systematic review (for example, when researchers meta-analyse results from a limited set of studies that they have conducted).

APPENDIX

Table II: HICPAC’s”Literature review: Mask References”

HICPAC’s “Literature review” is a list that begins on Slide 49. For readability, I have formatted the list in table form. Table is sorted with Masks (“M”) first, then Adverse Events (“AE”). Although this post only covers masks, all the references are provided as a service.

| # | M/AE | Country | FT/A | Date | Study Type | Study Method | Author(s) | Title | Journal |

| 26 | M | China | FT | 2011 | RCT | T | MacIntyre CR, Wang Q, Cauchemez S, Seale H, Dwyer DE, Yang P, et al. | A cluster randomized clinical trial comparing fit-tested and non-fit-tested N95 respirators to medical masks to prevent respiratory virus infection in health care workers | Influenza Other Respir Viruses |

| 27 | M | China | FT | 2014 | RCT | T | MacIntyre CR, Wang Q, Rahman B, Seale H, Ridda I, Gao Z, et al. | Efficacy of face masks and respirators in preventing upper respiratory tract bacterial colonization and co-infection in hospital healthcare workers | Prev Med |

| 28 | M | China | FT | 2013 | RCT | T | MacIntyre CR, Wang Q, Seale H, Yang P, Shi W, Gao Z, et al. | A randomized clinical trial of three options for N95 respirators and medical masks in health workers | Am J Respir Crit Care Med |

| 39 | M | United States | FT | 2019 | RCT | O | Radonovich LJ, Jr., Simberkoff MS, Bessesen MT, Brown AC, Cummings DAT, Gaydos CA, et al. | N95 Respirators vs Medical Masks for Preventing Influenza Among Health Care Personnel: A Randomized Clinical Trial | Jama |

| 23 | M | Canada, Israel, Pakistan, and Egypt | FT | 2022 | Randomized Trial | T | Loeb M, Bartholomew A, Hashmi M, Tarhuni W, Hassany M, Youngster I, et al. | Medical Masks Versus N95 Respirators for Preventing COVID-19 Among Health Care Workers | Annals of Internal Medicine |

| 24 | M | Canada | FT | 2009 | Randomized Trial | T | Loeb M, Dafoe N, Mahony J, John M, Sarabia A, Glavin V, et al. | Surgical Mask vs N95 Respirator for Preventing Influenza Among Health Care Workers: A Randomized Trial. | JAMA |

| 5 | M | Singapore | FT | 2010 | Observational | Q | Ang B, Poh BF, Win MK, Chow A. | Surgical masks for protection of health care personnel against pandemic novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1)-2009: results from an observational study | Clin Infect Dis |

| 11 | M | Italy | FT | 2020 | Observational | Q | Gelardi M, Fiore V, Giancaspro R, La Gatta E, Fortunato F, Resta O, et al. | Surgical mask and N95 in healthcare workers of Covid-19 departments: clinical and social aspects | Acta Biomed |

| 12 | M | United States | FT | 2021 | Observational | Q | Haas BT, Greenhawt M. | Association between type of personal protective equipment worn and clinician self-reported COVID-19 infection | The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice |

| 17 | M | India | FT | 2021 | Observational | Q | Khurana A, Kaushal G, Gupta R, Verma V, Sharma K, Kohli M. | Prevalence and clinical correlates of COVID-19 outbreak among health care workers in a tertiary level hospital in Delhi | Am. J. Infect. Dis |

| 29 | M | United States | A | 2000 | Observational | Q | Manangan LP, Bennett CL, Tablan N, Simonds DN, Pugliese G, Collazo E, et al. | Nosocomial tuberculosis prevention measures among two groups of US hospitals, 1992 to 1996 | Chest |

| 32 | M | Greece | FT | 2022 | Observational | Q | Mouliou DS, Pantazopoulos I, Gourgoulianis KI. | Medical/Surgical, Cloth and FFP/(K)N95 Masks: Unmasking Preference, SARS-CoV-2 Transmissibility and Respiratory Side Effects | J Pers Med |

| 36 | M | Italy | FT | 2020 | Observational | T | Piapan L, De Michieli P, Ronchese F, Rui F, Mauro M, Peresson M, et al. | COVID-19 outbreak in healthcare workers in hospitals in Trieste, North-east Italy | J Hosp Infect |

| 7 | M | France | FT | 2022 | Matched case-control | Q | Belan M, Charmet T, Schaeffer L, Tubiana S, Duval X, Lucet JC, et al. | SARS-CoV-2 exposures of healthcare workers from primary care, long-term care facilities and hospitals: a nationwide matched case-control study | Clin Microbiol Infect |

| 46 | M | France | FT | 2022 | Cross-sectional | Q | Wilson S, Mouet A, Jeanne-Leroyer C, Borgey F, Odinet-Raulin E, Humbert X, et al. | Professional practice for COVID-19 risk reduction among health care workers: A cross-sectional study with matched case-control comparison | PLoS One |

| 14 | M | Switzerland | FT | 2022 | Cohort | Q | Haller S, Güsewell S, Egger T, Scanferla G, Thoma R, Leal-Neto OB, et al. | Impact of respirator versus surgical masks on SARS-CoV-2 acquisition in healthcare workers: a prospective multicentre cohort | Antimicrob Resist Infect Control |

| 21 | M | United States | FT | 2021 | Cohort | O | Li A, Slezak J, Maldonado AM, Concepcion J, Maier CV, Rieg G. | SARS-CoV-2 Positivity and Mask Utilization Among Health Care Workers | JAMA Network Open |

| 25 | M | Canada | FT | 2004 | Cohort | O | Loeb M, McGeer A, Henry B, Ofner M, Rose D, Hlywka T, et al. | SARS among critical care nurses, Toronto. | Emerg Infect Dis |

| 47 | M | China | FT | 2020 | Cohort | T | Xie Z, Zhou N, Chi Y, Huang G, Wang J, Gao H, et al. | Nosocomial tuberculosis transmission from 2006 to 2018 in Beijing Chest Hospital, China | Antimicrob Resist Infect Control |

| 10 | M | United States | FT | 2021 | Clinical Trial | Q | Cummings DAT, Radonovich LJ, Gorse GJ, Gaydos CA, Bessesen MT, Brown AC, et al. | Risk Factors for Healthcare Personnel Infection With Endemic Coronaviruses (HKU1, OC43, NL63, 229E): Results from the Respiratory Protection Effectiveness Clinical Trial (ResPECT) | Clin Infect Dis |

| 45 | M | United States | A | 2009 | “Retrospective Review” | T | Welbel SF, French AL, Bush P, DeGuzman D, Weinstein RA. | Protecting health care workers from tuberculosis: a 10-year experience | Am J Infect Control |

| 42 | AE | Taiwan | FT | 2021 | RCT | Q | Su CY, Peng CY, Liu HL, Yeh IJ, Lee CW. | Comparison of Effects of N95 Respirators and Surgical Masks to Physiological and Psychological Health among Healthcare Workers: A Randomized Controlled Trial | Int J Environ Res Public Health |

| 2 | AE | Iran | FT | 2022 | Observational | O | Aliabadi M, Aghamiri ZS, Farhadian M, Shafiee Motlagh M, Hamidi Nahrani M. | The Influence of Face Masks on Verbal Communication in Persian in the Presence of Background Noise in Healthcare Staff | Acoust Aust |

| 4 | AE | Turkey | FT | 2022 | Observational | O | Altun E, Topaloglu Demir F. | Occupational facial dermatoses related to mask use in healthcare professionals | Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology |

| 16 | AE | Turkey | FT | 2021 | Observational | Q | İpek S, Yurttutan S, Güllü UU, Dalkıran T, Acıpayam C, Doğaner A. | Is N95 face mask linked to dizziness and headache? | Int Arch Occup Environ Health |

| 19 | AE | Poland | FT | 2020 | Observational | Q | Krajewski PK, Matusiak Ł, Szepietowska M, Białynicki-Birula R, Szepietowski JC. | Increased Prevalence of Face Mask—Induced Itch in Health Care Workers | Biology |

| 30 | AE | India | FT | 2021 | Observational | T | Manerkar HU, Nagarsekar A, Gaunkar RB, Dhupar V, Khorate M. | Assessment of Hypoxia and Physiological Stress Evinced by Usage of N95 Masks among Frontline Dental Healthcare Workers in a Humid Western Coastal Region of India-A Repeated Measure Observational Study | Indian J Occup Environ Med |

| 31 | AE | Italy | FT | 2021 | Observational | Q | Maniaci A, Ferlito S, Bubbico L, Ledda C, Rapisarda V, Iannella G, et al. | Comfort rules for face masks among healthcare workers during COVID-19 spread. | Ann Ig |

| 34 | AE | Korea | FT | 2021 | Observational | Q | Park SJ, Han HS, Shin SH, Yoo KH, Li K, Kim BJ, et al. | Adverse skin reactions due to use of face masks: a prospective survey during the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea | J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol |

| 37 | AE | Canada | A | 2022 | Observational | T | Pietrzyk AK, Eldehimi F, Nicolaou S, Yu SM, Forster BB. | The Effect of Mask Wearing on the Accuracy of Radiology Reports in an Academic Hospital Setting | Can Assoc Radiol J |

| 43 | AE | China | FT | 2020 | Observational | Q | Tang J, Zhang S, Chen Q, Li W, Yang J. | Risk factors for facial pressure sore of healthcare workers during the outbreak of COVID-19 | International Wound Journal |

| 48 | AE | Pakistan | FT | 2021 | Observational | Q | Zaib D, Naqvi F, Inayat S, Yaqoob N, Tahir K, Sarwar U, et al. | Cutaneous impact of surgical mask versus N 95 mask during covid-19 pandemic: Incidence of dermatological side effects and response of topical methylprednisolone aceponate (MPA) treatment to associated contact dermatitis | Journal of Pakistan Association of Dermatologists |

| 9 | AE | Turkey | A | 2022 | Observational | Q | Cigiloglu A, Ozturk E, Ganidagli S, Ozturk ZA. | Different reflections of the face mask: sleepiness, headache and psychological symptoms | Int J Occup Saf Ergon |

| 38 | AE | United States | FT | 2009 | Crossover | Radonovich LJ, Jr., Cheng J, Shenal BV, Hodgson M, Bender BS. | Respirator tolerance in health care workers | Jama | |

| 1 | AE | Iran | FT | 2022 | Cross‑sectional | Q | Abdi M, Falahi B, Ebrahimzadeh F, Karami-Zadeh K, Lakzadeh L, Rezaei-Nasab Z. | Investigating the Prevalence of Contact Dermatitis and its Related Factors Among Hospital Staff During the Outbreak of the COVID-19 Epidemic: A Cross-Sectional Study | Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res |

| 3 | AE | Singapore | A | 2022 | Cross-sectional | Q | Aloweni F, Bouchoucha SL, Hutchinson A, Ang SY, Toh HX, Bte Suhari NA, et al. | Health care workers’ experience of personal protective equipment use and associated adverse effects during the COVID-19 pandemic response in Singapore | J Adv Nurs |

| 6 | AE | Turkey | FT | 2020 | Cross-sectional | Q | Atay S, Cura Ş. | Problems Encountered by Nurses Due to the Use of Personal Protective Equipment During the Coronavirus Pandemic: Results of a Survey | Wound Manag Prev |

| 8 | AE | UK | FT | 2021 | Cross-sectional | Q | Burns ES, Pathmarajah P, Muralidharan V. | Physical and psychological impacts of handwashing and personal protective equipment usage in the COVID-19 pandemic: A UK based cross-sectional analysis of healthcare workers | Dermatol Ther |

| 13 | AE | Morocco | FT | 2020 | Cross-sectional | Q | Hajjij A, Aasfara J, Khalis M, Ouhabi H, Benariba F, Jr., El Kettani C. | Personal Protective Equipment and Headaches: Cross-Sectional Study Among Moroccan Healthcare Workers During COVID-19 Pandemic | Cureus |

| 15 | AE | Lebanon | FT | 2022 | Cross-sectional | Q | Hamdan A-L, Jabbour C, Ghanem A, Ghanem P. | The Impact of Masking Habits on Voice in a Sub-population of Healthcare Workers | Journal of Voice |

| 18 | AE | Turkey | FT | 2021 | Cross-sectional | Q | Köseoğlu Toksoy C, Demirbaş H, Bozkurt E, Acar H, Türk Börü Ü. | Headache related to mask use of healthcare workers in COVID-19 pandemic | Korean J Pain |

| 20 | AE | India | FT | 2023 | Cross-sectional | Q | Laxmidhar R, Desai C, Patel P, Laxmidhar F. | Adverse Effects Faced by Healthcare Workers While Using Personal Protective Equipment During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Civil Hospital, Ahmedabad | Cureus |

| 22 | AE | China | FT | 2022 | Cross-sectional | Q | Liu N, Ye M, Zhu Q, Chen D, Xu M, He J, et al. | Adverse Reactions to Facemasks in Health-Care Workers: A Cross-Sectional Survey. | Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol |

| 33 | AE | Nigeria | FT | 2021 | Cross-sectional | O | Nwosu ADG, Ossai EN, Onwuasoigwe O, Ahaotu F. | Oxygen saturation and perceived discomfort with face mask types, in the era of COVID-19: a hospital-based cross-sectional study | Pan Afr Med J |

| 35 | AE | Portugal | FT | 2022 | Cross-sectional | Q | Peres D, Monteiro J, Boléo-Tomé J. | Medical masks’ and respirators’ pattern of use, adverse effects and errors among Portuguese health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study | Am J Infect Control |

| 40 | AE | Spain | FT | 2020 | Cross-sectional | Q | Ramirez-Moreno JM, Ceberino D, Gonzalez Plata A, Rebollo B, Macias Sedas P, Hariramani R, et al. | Mask-associated ‘de novo’ headache in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic | Occup Environ Med |

| 41 | AE | Italy | FT | 2021 | Cross-sectional | Q | Rapisarda L, Trimboli M, Fortunato F, De Martino A, Marsico O, Demonte G, et al. | Facemask headache: a new nosographic entity among healthcare providers in COVID-19 era | Neurological Sciences |

| 44 | AE | China | FT | 2022 | Cross-sectional | Q | Wan X, Lu Q, Sun D, Wu H, Jiang G. | Skin Barrier Damage due to Prolonged Mask Use among Healthcare Workers and the General Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Survey in China | Dermatology |

LEGEND

M/AE: Mask, Adverse Events.

T/Q/O: Testing, Questionnaire, Other

FT/A: Full Text, Abstract

It occurs to me that some of the “Gish Gallops” I have encountered on masks are derived from this list, but being pressed temporally, I have not had time to check.