By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street.

This is amazing, and I’m not sure how long it will last, but spending on construction projects for manufacturing facilities in the US continues to spike in a historic manner. In September, $17.5 billion, up by about 150% from the stagnation range before the pandemic.

For the first nine months of 2023, spending on factory construction jumped to $140 billion, up by 131% from $60 billion in the same period in 2019 and $59 billion in 2021.

Since January 2021, roughly when this boom started, spending has nearly tripled. The rate of spending over the past five months exceeds $200 billion annualized (not seasonally adjusted).

Factory construction announcements continue. For example, just this week, German industrial giant Siemens announced that it will invest $510 million in the US to build factories: $150 million for a factory in Texas to manufacture electrical equipment for data centers; $220 million for a factory in North Carolina to manufacture passenger rail cars and offer overhauls of railcars and locomotives (Siemens diesel-electric locomotives are used by Amtrak, Brightline, and other passenger railroads); and $140 million for factories in Texas and California to manufacture electrical products.

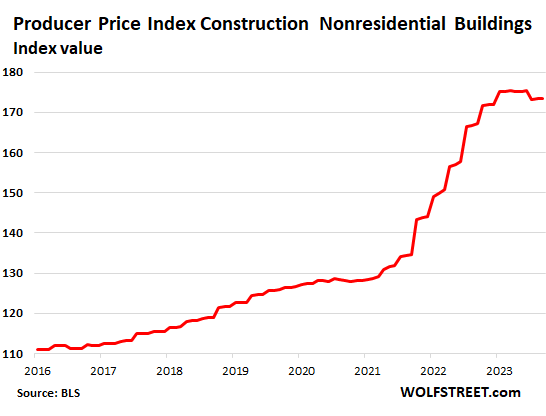

Part was inflation, but construction costs have cooled. Over the 33 months since January 2021, the Producer Price Index for nonresidential construction has surged by 35%. Over the same period, spending on factory construction has spiked by 195%.

But the PPI has actually declined a little so far this year. And the huge year-over-year gains have been whittled down to just 3.8% by September.

And there are lot more dollars involved. Construction spending just covers the buildings. Companies invest in factories in the US to make high-value technologically advanced products such as semiconductors and vehicles. They use highly automated factories full of industrial robots. Then there is other investment activity to support the factory, including infrastructure construction. The whole package counts as investments in GDP. What’s even more important for the economy is what comes later when the factory starts producing, creating its own ecosystem of economic activity.

Industrial robots cost about the same in the US as in China. The cost of labor is still very different. And other costs are different. But on the plus side are shorter lead times, less transportation expense, less geopolitical uncertainty, more control over IP, etc.

Taxpayers are shanghaied into subsidizing factory construction at the local, state, and federal level, and this has been going on forever.

What is new is the disruption experienced by global supply chains – they practically all run through China – during the pandemic that led to shortages of all kinds. In addition, there are all kinds of frictions, disputes, uncertainties, and tariffs between the US and China. US manufacturers have to toe the line in China. Even Musk, a big defender of free speech, is mouse-quiet in China about free speech. His gigafactory in Shanghai is worth a lot more than free speech, that’s for sure.

What’s also new are huge federal subsidies for semiconductor manufacturing plants, EV battery plants, and EV assembly plants, and subsidies for purchases of EVs that conform to geographic production limitations. Makers of computer, electronic, and electrical equipment are also big drivers behind the surge of factory construction, according to an analysis by the Treasury Department.

But wait… the construction boom took off in the spring of 2021. Over a year later, in July 2022, Congresses passed a package of subsidies for select manufacturing industries, such as semiconductor makers (up to $52 billion). But construction spending doesn’t immediately happen when the law is passed. The government takes its time actually handing out the money. And these big construction projects themselves take a while time before construction can even start. So a portion of those subsidies for factory construction are likely to provide further fuel going forward.

By output, the US is the second largest manufacturing country behind China, and has a greater share of global production than the next three combined (Germany, Japan, and India). The majority of motor vehicles sold in the US are assembled in factories in the US. All major foreign brands have assembly plants in the US. Tesla makes vehicles in the US, including for export.

But the US, as the largest economy in the world, has fallen far behind China in manufacturing, while many sectors have become dependent on manufacturing in China. And issues during the pandemic, including the semiconductor shortages, were a brutal wakeup call.