Yves here. Below is a continuation of KLG’s series: Science is not our friend, especially when it is not intended to be, which is often.The poor quality of the typical American diet is becoming a heath crisis, which also means to a degree a political football, with some of the arguably worst examples like super-sized sodas, coming under attack via sin taxes. Only recently have concerns about ultra-processed foods garnered mainstream media coverage. A complicating factor is varying definitions of what ultra-proceeded amounts to, accompanied by arguments that some ultra-processed items are not that bad.

By KLG, who has held research and academic positions in three US medical schools since 1995 and is currently Professor of Biochemistry and Associate Dean. He has performed and directed research on protein structure, function, and evolution; cell adhesion and motility; the mechanism of viral fusion proteins; and assembly of the vertebrate heart. He has served on national review panels of both public and private funding agencies, and his research and that of his students has been funded by the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and National Institutes of Health.

Our “Great American Food System” has become the problem it was meant to solve. Rather than feeding the us with a healthy and sufficient diet, it is starving us of the good food we need to thrive as human beings, while producing highly marketable and profitable food-like substances that are, how shall we put it, problematic. This is a truism among a comparative few, including Wendell Berry, Wes Jackson, and Chris Smaje, [1] and an outrageous slander to the usual suspects, Big Ag and Big Food. Nevertheless, recognition that the ultra-processed food-like substances (UPF) we eat are associated with, and likely the cause of, serious illness is being discussed, finally. Here, for example, in the NC link from January that led me, as a tutor of medical students, to catch up in another attempt to more fully understand diet and health.

Other available references taking a serious view of the problem include US Policies Addressing Ultraprocessed Food, 1980-2022, published in American Journal of Preventive Medicine by a group of researchers led by Jennifer L. Pomeranz of NYU. As might be expected, American “policymakers” have not done very much, but the 2025-2030 Advisory Committee on Dietary Guidelines is expected to take up the issue. The successive Diet Pyramids associated with this task have not been very useful. Nevertheless, the early preemptory (they hope), responses from Big Ag/Big Food are predictable (perfect photograph of UPF at the link):

Frozen food makers and the meat industry…speaking to a panel of nutrition experts tasked by the federal government with advising on the next round of the national dietary guidelines, raised concerns with its focus on that fare. So too did a coalition that includes the bakery, candy, corn syrup, and sugar lobbies, and the Consumer Brands Association, which includes General Mills, Kellogg’s, and Hostess…the North American Meat Institute, which represents companies like Hormel and Johnsonville, said Tuesday that ‘the scientific evaluation of the role of ultra-processed foods in health outcomes is premature’ and that ‘classifying foods as ultra-processed oversimplifies the complex issue and is not appropriate for the dietary guidelines…Food processing can provide benefits to products including food safety and security, improved nutrition, reducing food waste, permitting food diversity, and offering convenience and affordability,’ said Allison Cooke, a vice president at the Corn Refiners Association, which represents makers of corn syrup and other corn products. Cooke was representing the food coalition, the Food and Beverage Issue Alliance, which the corn refiners group chairs. (emphasis added)

Regarding affordability, the CEO of Kellogg’s recently made his case to inflation-challenged families: “Cereal, it’s what’s for dinner!” (a somewhat tiresome CNBC video, 3:53 after obligatory ad; watch on 2x). Nothing said about nutrition, nor would that be expected. For those who do not watch American television, compare with this from 2000, featuring Sam Elliott and Aaron Copland. That meal looks quite good and nourishing, with beef or chicken.

What are ultra-processed foods (UPF) using the NOVA classification system (pdf)? A simplified Table 1 is derived from Pomeranz et al:

This makes both intuitive and scientific sense. And it stands to reason after minimal consideration that a diet comprising NOVA Groups 1, 2, and 3 it will be a healthy diet. This case has been made very well in Ultra-Processed People: The Science Behind Food That Isn’t Food (Norton, 2023), which will be our guide. The author Chris van Tulleken has a PhD in Molecular Virology and a medical degree (MBBS: Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery). He is currently a practicing physician in infectious disease in London and a well-known, award-winning presenter on British television.

He has also written a very good book about a most important topic, one that begins with the perfect vignette: “Every Wednesday afternoon in the laboratory where I used to work, we had an event called journal club…” The word ‘club’ is a misnomer; this is not fun. However, it is how one learns to think about science and do be a good scientist. In my long experience those who participate in a Journal Club become good scientists or find another life. How it works: The speaker of the day picks a topic, usually based on one or two recent publications. If the papers are as good as expected, everyone learns something. If the papers are not as good as expected, everyone learns even more, including the presenter. After getting ripped to shreds – clubbed – once or twice in the “critical but supportive environment” (that’s what I tell my students) the graduate student, postdoc, or even professor learns how to read and interpret the scientific literature beyond the Abstract and Summary paragraphs. No, Journal Club is not fun, but it is rewarding. And essential. As we have come to learn in the current scientific world, the details always matter. Everyone gets it wrong sometime, but those who have been challenged at every step of the way, from apprentice to independent scientist, get it wrong a lot less often. This is something we have largely lost, and it shows. Chris van Tulleken proceeds with his exposition much as he would in his old Journal Club, and his readers are the better off for this.

The most important attribute of a popular book that covers something as important as UPF and their effects on us is how close the book follows the primary literature. Although no one can cover everything, Ultra-Processed People does very well from the beginning. Others who have done well on food, diet, nutrition, and health include Gary Taubes(something of a lightning rod). But his The Case Against Sugar and Good Calories, Bad Calories are very good; I have just begun to read his Rethinking Diabetes, and it looks quite promising. Michael Moss, whose Salt, Sugar, Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us was one of the earliest full-length treatments of the “food science” and “bliss point” essential to UPF, is also very good. Taubes and Moss are reporters who get it right. The physician Siddhartha Mukherjee is very good for the serious reader on cancer, the gene, and the cell, all relevant to what is covered here. Nick Lane is a biochemist who is always engaging about essentials. Each is a worthy successor to Stephen Jay Gould and Carl Sagan and Lewis Thomas.

In the spirit of a Journal Club, it is my view that van Tulleken slightly misses the mark on the harm done by sugar, as covered extensively by Taubes (graciously acknowledged in the book), Robert Lustig, and the earlier, foundational work of John Yudkin. I personally anticipate that the damage done by excessive levels of dietary fructose will eventually be identified. Although UPF are clearly deleterious to human health, this is also because of manipulation of salt and sugar and fat, the latter in forms that are novel components of the human diet (e.g., palm oil, high-fructose corn syrup, invert sugar, dimethylpolysiloxane, which is something that should never be consumed). There is probably no way to tease apart these strands, but high glucose/sugar means high insulin. Insulin is our primary anabolic hormone and the natural response to a high carbohydrate diet is to store that potential energy as fat. For the past 50 years fat and protein calories in the American diet have been replaced by carbohydrates. This has led to the obesity epidemic associated with metabolic syndrome. Persistently elevated insulin will lead to insulin insensitivity manifested in Type-2 diabetes. Type-1 diabetes is due to insulin insufficiency caused by autoimmune obliteration of insulin-producing cells in the pancreas.

Ultra-Processed People begins with two fundamental papers that frame his thesis. The first is the original publication from Carlos Augusto Monteiro and coworkers from Brazil, in which ultra-processed food (UPF) was defined: A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing (pdf). This comes directly out of recognition of the damage UPF does, for example, in the form of the Nestlé [2] Floating Supermarket:

Nestlé Até Vocâ a Bordo (Nestlé Takes You Onboard) was a huge floating supermarket staffed by eleven people, which would leave from Belém…and travel hundreds of miles upriver, serving 800,000 people in remote Amazonian communities. According to the press release, ‘Nestlé aims at developing another trading channel which offers access to nutrition, health and wellbeing to the remote communities of the north region’…On the day that press release was issued, Nestle’s website claimed: ‘Our core aim is to enhance the quality of consumers’ (keyword) lives every day, everywhere by offering tastier and healthier food and beverage choices and encouraging a healthy lifestyle.’ (emphasis added)

So, what happened in these communities? The first thing was that sales of the Nestlé UPF brought prices down under the aggregate prices of the local market. These low prices made life harder (impossible) for local traders of whole foods, and the shop on the boat “went from being a luxury to an essential service.” Normal business practice for a transnational corporation: Undersell the locals until they disappear and then reap the “benefits” as the essential supplier. Paula Costa Ferriera (a local teacher in Muaná, an Amazonian community served by the floating supermarket) went on to tell van Tulleken about several local children with Type-2 diabetes, where there should be no children with this diet-related disease. There is no “evidence that there were children with diet-related diabetes in these parts of Brazil until enterprises like the Nestle boat.”

And “Everyone, from the shopkeepers (and) teachers and the people working for the NGOs agrees: It all started with the boat. Almost everyone we met…was living with obesity.” Where have we seen this before? In the food deserts of North America, which are common in small and large, rural and urban communities throughout the United States [3]. But not only in food deserts. Just look around, and compare the prosperous suburban American with the citizens of France, Italy, and Spain. Or to the average American of 1967, before UPF were so widely marketed and consumed. No, correlation is not causation, but if there is a plausible mechanism connecting the correlative values, a mechanism is likely to be lurking nearby.

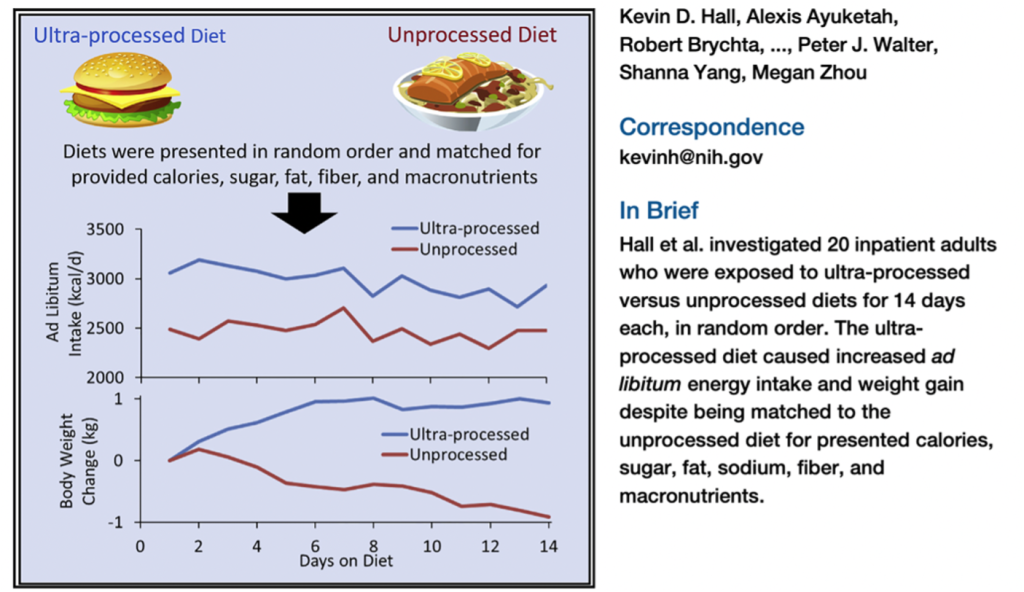

The second scientific paper is Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: An inpatient randomized control trial of ad libitum food intake (pdf) by Kevin D. Hall at the US National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and associates, most of whom are also at NIH. A graphical abstract of the paper is presented below. In brief, ten (10) adults were given a diet of unprocessed food and ten (10) others were given a diet of UPF and were followed for two weeks. Each subject could eat as much or as little as desired (ad libitum). The two main results were: (1) those on the UPF diet consumed about 500 more calories per day than those on the unprocessed diet, and (2) those on the UPF diet gained weight while those on the unprocessed diet lost weight. These results stand out, but this is also a short experiment with only 20 subjects. A letter in the same issue of Cell Metabolism (Ultra-processed Food and Obesity: The Pitfalls of Extrapolation from Short Studies) raises several points worth considering, including the size of this trial and its duration. Deficiencies in random controlled clinical trials (RCT) have been discussed here often. But in this case, the original result from 2019 has apparently held up well and is supported throughout Ultra-Processed People. Small experiments and RCTs, well designed and conducted with no outside influence, are often very useful as scientific products in the tangle of science as defined by Nancy Cartwright and others, discussed here previously. The size of the trial or the experiment is not necessarily relevant to the validity of the result [4].

One example: Why do people eat more UPF than real food? A calorie is not a calorie except in a bomb calorimeter. Without going into detail, where I would hang by my fingertips, the thermodynamics of nutrition is not path independent. What you eat matters along with how many calories. This is covered in Chapter 11, UPF is pre-chewed. This is frankly a gross concept, but it explains much about the allure of UPF. As noted by Anthony Fardet of the Human Nutrition Unit at Université Clermont Auvergne, the ‘food matrix’ – the physical structure of food – matters in the human diet. As an example, an apple is a normal component of the human diet. Apple juice, not so much. The body’s responses to an apple, apple juice, and apple puree are not equivalent. Blood sugar and insulin spike higher with the apple juice and puree than the apple, followed by a crash. Or, “Our bodies have evolved to manage the sugar load from an apple precisely, but fruit juice is a relatively new invention.” Yes, “an apple a day may keep the doctor away.” A diet filled with sugar-laden fruit juice or its ultra-processed equivalent containing high-fructose corn syrup likely will not. Same for a diet of UPF.

An early example in the book recounts a breakfast scene with Lyra, van Tulleken’s young daughter, by comparing a McDonald’s hamburger to her Coco Pops (Cocoa Krispies in the US, i.e., chocolate-flavored Rice Krispies, which I remember well, along with what were called Sugar Frosted Flakes and Sugar Crisp in the 1960s). The McDonald’s hamburger is designed to be soft, creamy, spongy, salty, and to be eaten in as little as a minute, too fast for satiety mechanisms to respond. So, you eat another. And the super-size order of fries to go along with the 32-ounce soft drink or “shake” (no milk included?) and maybe the ersatz ice cream. Same with Coco Pops, which are soft, sweet, easily digested. That is, essentially pre-chewed. They are designed to eaten quickly without time to send the signal to the brain that you are full and it’s time to stop eating. This is probably the main reason the UPF subjects in the RCT/experiment directed by Kevin Hall at NIH consumed 500 more calories per day than those on the unprocessed diet. It takes “work” to eat real food, and this also has consequences. Those who eat whole food have stronger jaw muscles and longer jaws than those who do not. A diet of UPF keeps general dentists, orthodontists, and endodontists busy.

UPF is designed to be overconsumed (Chapter 18). A summary on the science of UPF and the human body:

- Destruction of the food matrix by physical, chemical, and thermal processing softens UPF so that they are eaten fast, with the consumption of more calories per minute without feeling satiated.

- UPF generally have a high calorie density because they are dry, high in fat and sugar, and low in fiber, which means more calories per mouthful.

- UPF displace diverse whole foods in the diet, especially among low-income groups (UPF is cheap at the cash register but only there) and are often micronutrient-deficient despite the normal load of additives. The proper measures of a diet lie in food, not in the individual chemical compounds and minerals that are essential for life. These are often not particularly useful in any case. Fish is good if it is not farmed or loaded with mercury. Fish oil (omega-3 fatty acids) in capsules from the supplement store, not so much.

- The mismatch between taste signals and nutrition content of UPF alter metabolism by mechanisms not completely understood, but the obesity epidemic of the past 50 years is clear indication this happens. Artificial sweeteners may have a role in this.

- UPF are designed essentially to be addictive, so binges are unavoidable. See Sugar Salt Fat. How many of us have consumed, not eaten, an entire bag of potato chips or a tube of Thin Mints at one sitting?

- The emulsifiers, preservatives, modified starches, and other additives are likely to damage the gut microbiome. The microbiome is relatively new to biomedical science, slowly coming into focus in the past fifteen years, but it clearly has broad effects on human health from the brain to the heart. The ostensibly harmless additives to UPF are likely to dysregulate the gut microbiome and lead to inflammation. Chronic inflammation, a concomitant of obesity, is a risk factor for cancer and a host of other diseases.

- Convenience, price, and marketing of UPF are intentionally designed to prompt us to eat recreationally. Snack, snack, snack.

- Additives and physical processing required for the palatability of UPF dysregulate our satiety system. Other additives probably affect brain and endocrine function. Plastics are essential to the marketing of UPF and are another negative externality altogether.

- The production of UPF requires expensive subsidies (i.e., negative externalities associated with Big Ag production of GMO corn and soybean as commodity crops) that lead to environmental damage caused by industrial agriculture. This includes damage to the human and built environment of rural areas and chemical pollution caused by runoff of pesticides, herbicides, nitrogen, and phosphorous. The dead zone at the mouth of the Mississippi River is the most glaring example of the latter.

Where do we go from here? Modern obesity is clearly a commerciogenic disease resulting in a particularly insidious form of malnutrition. In the US, the FDA and USDA might act, but regulatory capture makes this unlikely. The medical profession is the one profession that could act and gain traction. Maybe it will. But there is too much money to be made from UPF as a product of Big Food, Big Ag, and industrial agriculture, which makes hope something of a dream. Countries with a still healthy food culture could show the way forward is actually to look to the past. Although commerciogenic obesity is a multifactorial problem, it may be no accident that life expectancy in these countries, France, Spain, and Italy, for example, is higher than in the US, before and after the pandemic dip.

It has been said that no one can save the world. True. But each of us can save the world one person, one family, one local economy, one at a time. We should once again eat where we live and live where we eat. The world will get smaller in the coming inconvenient apocalypse. We will have no choice but to take care of ourselves locally. We can do this work well or not at all. Our decision, but ultra-processing in all its guises will not be part of the solution. And the food will taste better.

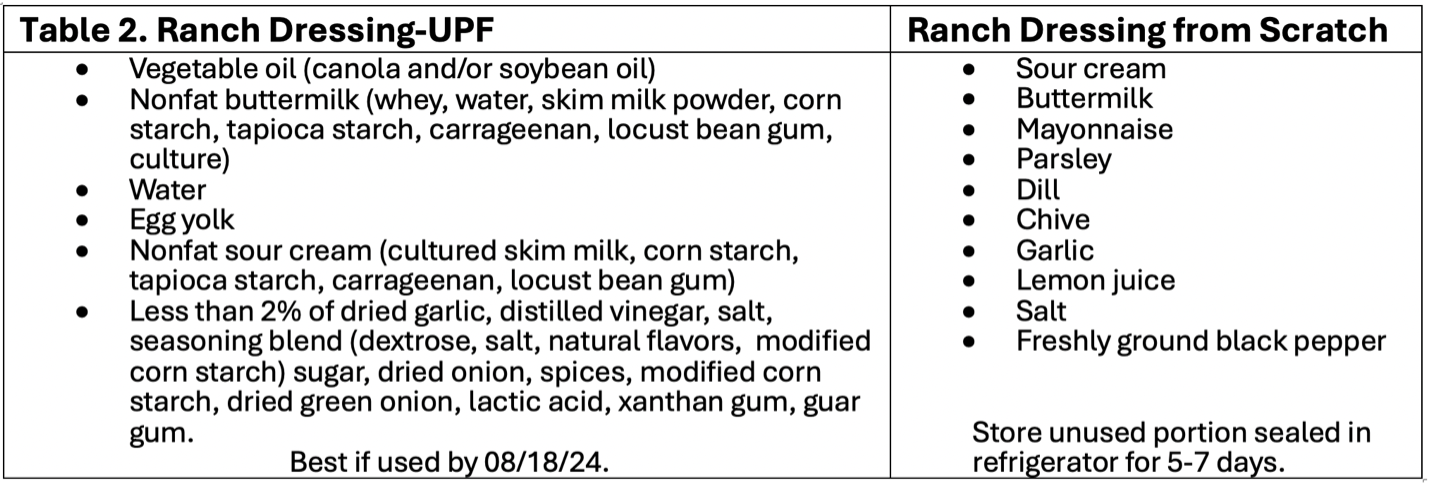

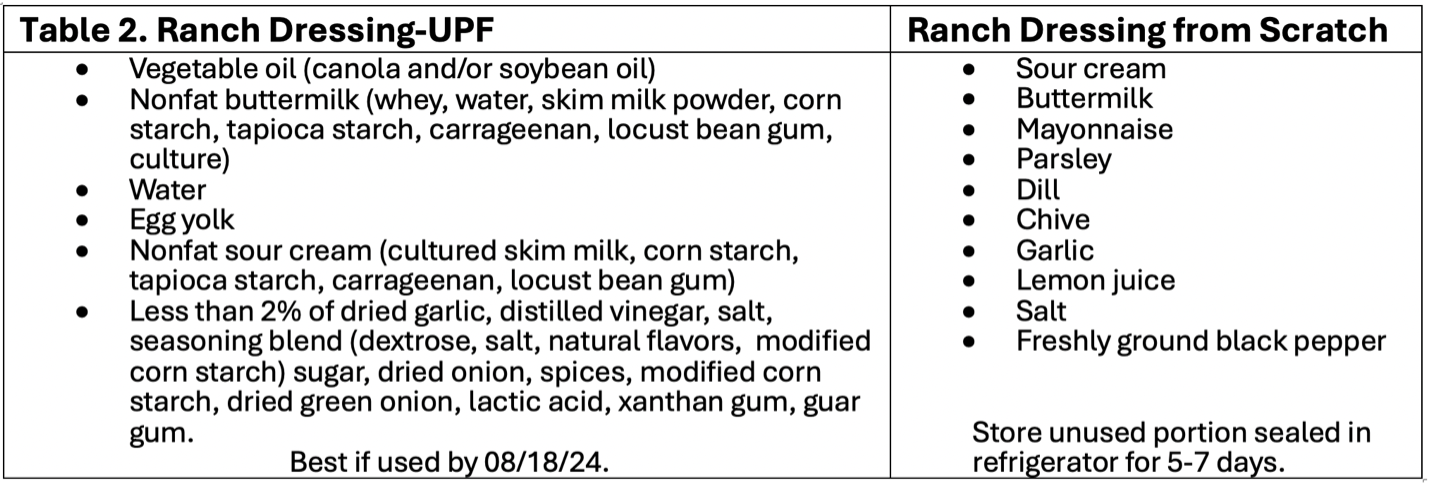

Coda. Last week I was alone at home and grazing healthily, or so I thought. Raw vegetables and fizzy water, cheese, and non-industrial sourdough bread. The broccoli was good, dipped lightly in the “natural” ranch dressing I had purchased the day before. I had already planned this essay, so I began to wonder what I was eating. This made me look at the label. Ha! My UPF natural ranch dressing is compared below with ranch dressing made from scratch (Table 2).

Escape is difficult. The UPF “nonfat” buttermilk on the left isn’t. Ditto for the sour cream. Who knows what the natural flavors and spices are? But the UPF product lasts a very long time, which is the point. Next time I will take the one on the right and leave the UPF behind. I am fortunate to be able to do so. The price will not be higher, except in time and convenience, and I am fortunate that the latter are possible for me. As Ultra-Processed People concludes: The goal should be that we live in a world where we have real choices about what we eat and the freedom to make them. Yes, that would be a good start, one meal at a time.

Notes

[1] Wendell Berry is a constant in this series. Wes Jackson and Chris Smaje have figured in two previous posts. Smaje recently published an excellent essay on his argument with George Monbiot on the nature of food and farming at Front Porch Republic, which could use a bit more serious Left Conservatism in its content, such as their special issue of Local Culture on the life and work of Christopher Lasch (pdf).

[2] Virtually every product sold by Nestlé is UPF, including baby formula. In the 1970s Nestlé sent saleswomen dressed to resemble nurses to what were at the time called “third world” countries to hawk its powdered baby formula (UPF) as a better alternative to breast feeding. New mothers were frequently given free formula immediately after birth, which often foreclosed breast feeding as a subsequent option. In places where the safety of drinking water could be in question, especially for infants, the consequences were predictable. More recently Nestle has gone all-in on bottled water, which was a very early indicator to me that we were completely losing the plot, while filling the world with plastic waste.

[3] I remember well an outright confrontation with a first-year medical student during a biochemistry group tutorial when the socio- and commerciogenic nature of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and Type-2 diabetes came up during discussion. He replied that “it didn’t matter what you tell these people, they won’t listen.” He learned about food deserts on the spot, some of which are in easy walking distance of where we sat at that moment, places where the only sources of “food” are “convenience stores” that sell soft drinks, potato chips, candy, beer, cigarettes, and lottery tickets in a city with a severe maldistribution of legitimate grocery stores and barely functioning public transit.

[4] I have repeatedly mentioned in this series that a scientific paper has not been read and understood absent an appreciation of who/what supported the work. Acknowledgment from the Hall paper: “This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. We thank the nursing and nutrition staff at the NIH MCRU for their invaluable assistance with this study. We also thank Ms. Shavonne Pocock for taking the photos of the study diets. We are most thankful to the study subjects who volunteered to participate in this demanding protocol.” Acknowledgment from the “Pitfalls” letter: “D.S.L. received royalties for books on obesity and nutrition that recommend a reduced glycemic load diet. A.A. is recipient of honoraria as speaker for a wide range of Danish and international concerns, and receives royalties from popular diet and cookery books on low glycemic load and personalized diets. S.B.H. is a member of the MedifastMedical Advisory Board. W.C.W. received royalties for books on nutrition and obesity. The other authors have no disclosures. This work was done without financial sponsorship.” I have not delved into Optavia, which is apparently the primary product/service of Medifast, Inc.