By Lambert Strether of Corrente

Once again I must put on my Mr. Pandemic™ hat, following up on the previous post, “Will Human-to-Human Bird Flu (H5N1) Be the Long-Awaited “Disease X?”,” and noting that — touch wood — Beveridge’s Law still applies. Displaying the sunny temperament for which I am so well-known, let me begin with some good news: We can test wastewater for H5N1. From the following preprint, “Detection of hemagglutinin H5 influenza A virus sequence in municipal wastewater solids at wastewater treatment plants with increases in influenza A in spring, 2024” (sadly, horrid Alphabet’s Verily, and not our old favorites, Biobot). From the Abstract:

Prospective influenza A (IAV) RNA monitoring at 190 wastewater treatment plants across the US identified increases in IAV RNA concentrations at 59 plants in spring 2024, after the typical seasonal influenza period, coincident with the identification of highly pathogenic avian influenza (subtype H5N1) circulating in dairy cattle in the US. We developed and validated a hydrolysis-probe RT-PCR assay for quantification of the H5 hemagglutinin gene. We applied it retrospectively to samples from three plants where springtime increases were identified. The H5 marker was detected at all three plants coinciding with the increases. Plants were located in a state with confirmed outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza, H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, in dairy cattle. Concentrations of the H5 gene approached overall influenza A virus gene concentrations, suggesting a large fraction of IAV inputs were H5 subtypes. At two of the wastewater plants, industrial discharges containing animal waste, including milk byproducts, were permitted to discharge into sewers. Our findings demonstrate wastewater monitoring can detect animal-associated influenza contributions, and highlight the need to consider industrial and agricultural inputs into wastewater. This work illustrates the value of wastewater monitoring for comprehensive influenza surveillance for diseases with zoonotic potential across human and animal populations.

It’s actually good news that finally we can have some sense of how much H5N1 there is out there, but at the same time, human-excreted and Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation (CAFO)-derived H5N1 both go into the same waste stream, as the authors themselves remark in the Discussion, so we can’t get a good reading on how many people have H5N1 from this data alone, i.e., whether there’s a pandemic or not (though I imagine some work could be done with location, i.e., non-CAFO sewersheds).[1]

ln the remainder of this post, I will first look what we now know about H5N1 transmission and mutation, and then at protecting the food supply from H5N1 (with an aside on characterizing H5N1 as a food supply problem; basically, at what is known today as opposed to what was known when last I posted. (Readers will, of course, supply any lacunae; it’s a fast-moving story). Finally, I consider the posssibility of an H5N1 pandemic in the light of the precautionary principle we so conspicuosly failed to apply in the current, ongoing pandemic, SARS-CoV-2.

H5N1 Transmission and Mutation

Here are all the examples of transmission between mammals (including humans) that I could find. (Here is a case of transmission from birds to dolphins).

Cattle to cattle and cats. From the CDC, “Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b Virus Infection in Domestic Dairy Cattle and Cats, United States, 2024.” This is, I believe, the epicenter of detection, though not necessarily “Cow Zero” as it were:

In February 2024, veterinarians were alerted to a syndrome occurring in lactating dairy cattle in the panhandle region of northern Texas. Nonspecific illness accompanied by reduced feed intake and rumination and an abrupt drop in milk production developed in affected animals. The milk from most affected cows had a thickened, creamy yellow appearance similar to colostrum. On affected farms, incidence appeared to peak 4–6 days after the first animals were affected and then tapered off within 10–14 days; afterward, most animals were slowly returned to regular milking. Clinical signs were commonly reported in multiparous cows during middle to late lactation; ≈10%–15% illness and minimal death of cattle were observed on affected farms….

In early March 2024, similar clinical cases were reported in dairy cattle in southwestern Kansas and northeastern New Mexico; deaths of wild birds and domestic cats were also observed within affected sites in the Texas panhandle. In >1 dairy farms in Texas, deaths occurred in domestic cats fed raw colostrum and milk from sick cows that were in the hospital parlor. Antemortem clinical signs in affected cats were depressed mental state, stiff body movements, ataxia, blindness, circling, and copious oculonasal discharge. Neurologic exams of affected cats revealed the absence of menace reflexes and pupillary light responses with a weak blink response.

On March 21, 2024, milk, serum, and fresh and fixed tissue samples from cattle located in affected dairies in Texas and 2 deceased cats from an affected Texas dairy farm were received at the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (ISUVDL; Ames, IA, USA). The next day, similar sets of samples were received from cattle located in affected dairies in Kansas. Milk and tissue samples from cattle and tissue samples from the cats tested positive for influenza A virus (IAV) by screening PCR, which was confirmed and characterized as [Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI)] H5N1 virus by the US Department of Agriculture National Veterinary Services Laboratory. Detection led to an initial press release by the US Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service [APHIS] on March 25, 2024….

Cattle to humans. From Stat, “What we’re starting to learn about H5N1 in cows, and the risk to people,” a vivid description of a “milking parlor” (there’s plenty more):

Milking parlors are typically enclosed buildings outfitted with individual stalls arranged in a ring or in rows where dairy cows are led two to three times each day to drain their udders of milk. In a milking operation, the stimulus to secrete milk comes not from the sight or touch of a calf but is usually provided by a farm worker. That person also cleans the animal’s teats with a damp cloth and then dips them into a disinfectant solution to protect them from infectious bacteria present on a farm. The teats are then attached to the milking unit, also called a claw, which consists of a cluster of four rubber or silicon-based liners that fit snugly around each teat. The milking lasts about six to nine minutes per animal, and then each cow receives another disinfectant treatment before it’s ushered out and another animal is brought in.

The problem is that the milking equipment that comes into contact with the cow’s udders is typically not sanitized between individual animals, said Nigel Cook, a professor in Food Animal Production Medicine at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and long-time dairy cow health researcher. Rather, sanitization steps happen only two or three times a day.

“Contamination of the milking unit with milk residue cross-contaminating to the next cow would be a risk — as it would with any mastitis pathogen,” Cook told STAT via email.

Liners also have to be regularly replaced, as wear and tear and chemical exposure make them lose their elasticity, becoming rough and split. When that happens, the liners are more difficult to disinfect and can act as a reservoir for infection.

Liners, dip cups, washrags, and milkers’ gloved hands are all possible means of spreading the virus from one animal to the next. Washrags used on different animals are often laundered together before repeat use, but some dairies don’t use hot water, and researchers have found genetic traces of H5N1 on both used and clean rags using PCR testing. More work is needed to figure out which vectors are playing the biggest role, scientists told STAT.

Only one human infection — a Texas dairy farm worker who developed conjunctivitis — has been reported, but anecdotal reports abound of other farm workers with conjunctivitis and mild respiratory symptoms. Scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are working to figure out where the biggest risks to these workers lie, Sonja Olsen, associate director for preparedness and response in CDC’s influenza division, said during the ASTHO symposium. Is it exposure to cows? Contact with milk? Are there specific activities on farms or in slaughterhouses that put people at elevated risk of contracting H5N1?

I assume “exposure to cows” means transmission “through the air,” and indeed that’s mentioned as possibility, which is refreshing. (It’s entirely possible for both fomite transmission through the “milking unit” and airborne transmission to occur.)

Wild animals generally. Here is a handy map of all the animals in which H5N1 is to be found, and where they occur’ some birds, lots of mammals (plus the oppossum, a marsupial). From APHIS:

(Given how deer infest so many suburban neighborhoods, it would be bad if they were carriers, but apparently the likelihood is low.)

Now, I don’t raise all these examples because they reach pandemic status, alone or together. I raise them because the more H5N1 is “out there,” the more likely it is that a mutation will occur that does reach pandemic status. From Time, “Why Experts Are Worried About Bird Flu in Cows“:

[Health experts are] watching how the virus moves from species to species and what genetic changes it picks up as it makes these jumps. Bird flu strains aren’t generally adept at infecting other species, including mammals. But the most recent case of bird flu in a person was also the first time the virus has been found in cows.

The fact that it’s now infecting cows—animals that people come in closer contact with than other mammals that have harbored H5N1, like foxes—means the viruses could potentially be mutating in ways that could spread and cause disease in significantly more people.

[Andrew Bowman, associate professor of veterinary preventive medicine at Ohio State University] says that the FDA’s report is concerning because it suggests that this particular strain of H5N1 is continuing to be transmitted among cows. ‘This is a spillover into a mammalian host that seems to be maintaining [the infection],’ he says. ‘In previous spillovers into mammals, it seemed to be for the most part individual events that were isolated and didn’t continue to spread in those species. This is different.’

“Every time another animal or human is infected, it’s another throw at the genetic roulette table in terms of whether the virus could become one that transmits from human to human, which is what is required for a pandemic,” says Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota. “If you throw enough times, you may end up with an outcome that you don’t want.”

(Osterholm’s “throw at the genetic roulette table” is Taleb’s “risk of ruin,” which we’ll get to when we discuss the Precationary Principle). In the meantime, at least one mutation has occurred. From Alexander Tin, “HHS press briefing on avian influenza”:

[MIKE WATSON, APHIS] Also on April 16th, USDA APHIS microbiologists identified a shift in the H5N1 sample, this is one sample from a cow in Kansas, that could indicate that the virus was mutating for adaptation to mammals.

However, CDC conducted further analysis of the specimen sequence and their assessment is low risk over all, of this one sample that has that change.

Oh. (CDC’s “low risk” is clearly not Taleb’s “risk of ruin.”)

Protecting the Food Supply from H5N1

Milk. From Stat, “H5N1 bird flu virus particles found in pasteurized milk but FDA says commercial milk supply appears safe“:

Testing conducted by the Food and Drug Administration on pasteurized commercially purchased milk has found genetic evidence of the H5N1 bird flu virus, the agency confirmed Tuesday. But the testing, done by polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, cannot distinguish between live virus or fragments of viruses that could have been killed by the pasteurization process.

The agency said it has been trying to see if it could grow virus from milk found to contain evidence of H5N1, which is the gold standard test to see if there is viable virus in a product. The lengthy statement the agency released does not explicitly say FDA laboratories were unable to find live virus in the milk samples, but it does state that its belief that commercial, pasteurized milk is safe to consume has not been altered by these findings.

“To date, we have seen nothing that would change our assessment that the commercial milk supply is safe,” the statement said.

The document was long on assurances but short on details of what has been undertaken or found. It does not specify how many commercial samples were taken or in how many markets, nor does it indicate what percentage of the samples were PCR-positive for H5N1. The statement did not indicate if the testing suggested the amounts of viral genetic material in the milk were low or high.

Beef. From ABC, “USDA says it is testing beef for H5N1 bird flu virus“:

The United States Department of Agriculture said on Monday that it is conducting three separate beef safety studies. The agency is sampling ground beef purchased at grocery stores in states where dairy cattle have tested positive for the H5N1 avian influenza virus. It is also taking samples of muscle tissue from sick cows that have been culled from their herd.

Finally, they’re conducting cooking studies, which will inoculate ground beef with a “virus surrogate” and cook it to different temperatures to see how much virus is killed under each heat setting.

The move comes as one country, Colombia, placed restrictions on beef and beef products coming from US states where dairy herds have tested positive for avian influenza.

Now, I don’t especially like the idea of H5N1 permeating my comestibles. By the same token, however, if the effects were anything like other food supply issues, it seems to me that some illness would already have shown up (especially given the appearance of H5N1 in the media). Cholera H5N1 is not (at least, so far, not in food).

My concerns go to the possibility that the various agencies involved — USDA, FDA, CDC — are treating H5N1 as a food supply problem, and not as a potential pandemic breakout problem. For example, here is what APHIS is focusing on:

APHIS is strengthening its ability to quickly respond to significant animal disease outbreaks by announcing a final rule amending the animal disease traceability regulations and requiring electronic ID for interstate movement of certain cattle and bison. https://t.co/h0MUvPbr8I pic.twitter.com/VSTEildFQv

— USDA APHIS (@USDA_APHIS) April 26, 2024

Very well. But what about the humans in the CAFO operations? To be fair, it is true that CDC is recommending PPE (and training) for farmers and workers who might be infected by H5N1:

CDC: H5N1 in cattle – PPE recommendations

“Farmers, workers, and emergency responders should wear appropriate PPE when in direct or close physical contact with sick birds, livestock, or other animals; carcasses; feces; litter; raw milk”https://t.co/ow03ebjpvs pic.twitter.com/SE7SG63qST

— CoronaHeadsUp (@CoronaHeadsUp) April 17, 2024

(One notes the bitter irony that both cattle and workers in CAFOs will be safer than patients and HCWs in hospitals, at least if CDC’s profit-driven HICPAC gets its way.) But why on earth does CDC’s guidance stop at the CAFO door? Why is there no testing of the farmers and workers? From MedPage, “Are We Testing Enough for H5N1?“:

“We really need to be moving quickly to get our heads around what’s happening in the animal population and also what’s happening in the human population,” James Lawler, MD, MPH, of the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Global Center for Health Security, told MedPage Today. “I don’t think we’ve been testing adequately to be able to get a real picture of that.”

Lawler said we should be particularly cautious “when a virus starts doing things that we don’t expect it to do, like circulating widely in a species where we normally haven’t seen infections. We really need to respect the potential danger that exists.”

Federal officials have confirmed that 33 dairy cattle herds in eight U.S. states have tested positive for H5N1. However, the outbreak is likely much larger than that, and has probably been spreading undetected for much longer than thought, Lawler said.

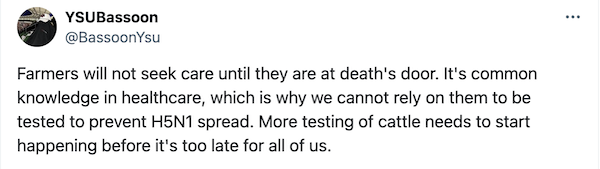

So we don’t really know how many humans are infected, do we? Farmers, culturally, don’t test:

(Many war stories online of farmers getting, say, an arm chewed up in a hay baler, binding themselves up, finishing the chores, and only then seeking medical help — quite possibly from the local veterinarian.)

Farmers also may have business reasons to evade testing. From the Daily Mail, “Large bird flu outbreak feared among Texas farmers – group shows symptoms of disease as experts warn cases are far more widespread than previously thought“:

Experts have warned that human transmission of bird flu may be far more widespread than thought, as farmers in Texas and Wisconsin are reported to have symptoms of the virus but are avoiding testing.

Dr Barb Petersen, a dairy veterinarian in Amarillo, Texas [the epicenter, remember], explained that workers at a local farm where cattle have tested positive for the virus are suffering tell-tale symptoms.

She said: ‘People had some classic flu-like symptoms, including high fever, sweating at night, chills, lower back pain,’ as well as upset stomach, vomiting and diarrhea.

They also tended to have ‘pretty severe conjunctivitis and swelling of their eyelids’.

Dr Keith Poulsen, director of the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, told NBC News that he had heard reports of people with the infection.

He added that farmers are not cooperating with demands to test in part because of their long hours and because of fears they may be asked to cull their herds — as poultry farmers are to their flocks.

(I would imagine that any undocumented migrants working at the farms would also be reluctant to test).

Anyhow, here the testing that has been done. From MedPage once more:

In the current outbreak, at least 44 people have been monitored for symptoms, the spokesperson said, and more are being passively monitored, where they monitor themselves and report if they develop symptoms.

Overall, 23 people have been tested by states, with only one person — a farm worker in Texasopens in a new tab or window whose only symptom was conjunctivitis — tested positive, the [CDC] spokesperson said.

But see Barb Petersen, just above, for how ridiculous that result is. It’s almost as if CDC is afraid of what they might find? What’s wrong with testing as many humans in the dairies right now?

Finally, the institutional structure — CDC, USDA, FDA — is a big problem. MedPage once more:

CDC spokesperson said that while the USDA is responsible for livestock testing, the agencies are “working together to characterize virus specimens and monitor for changes that might make these viruses more likely to transmit to or between humans.”

“Working together.” Do you know what that means? It means no one agency is in charge of preventing a pandemic. That’s what it means. (More CDC hooey here[2]). A safe, or at least a profitable, food supply we understand. Pandemics, we don’t. We seem not to want to.

Pandemics and the Precautionary Principle

Readers will recall that Norman, Bar-Yam, and Taleb of the New England Complex Systems Institute (NECSI) published “Systemic Risk of Pandemic Via Novel Pathogens – Coronavirus,” in which they in essence called eveything that should have been done to control the current pandemic, none of which — this being the stupidest timeline — was done, on January 26, 2020 (!!).

The essential takeaway is The Precautionary Principle:

The general (non-naive) precautionary principle [3] delineates conditions where actions must be taken to reduce risk of ruin, and traditional cost-benefit analyses must not be used. These are ruin problems where, over time, exposure to tail events leads to a certain eventual extinction. While there is a very high probability for humanity surviving a single such event, over time, there is eventually zero probability of surviving repeated exposures to such events. While repeated risks can be taken by individuals with a limited life expectancy, ruin exposures must never be taken at the systemic and collective level.

That is exactly what “we” — CDC, USDA, FDA, and on up — are doing with H5N1: exposing ourselves once more to the risk of ruin at the “systemic and collective level.” (Osterholm’s “throw at the genetic roulette table”). We don’t even know how many humans are infected with H5N1, and it’s out there mutating in [checks APHIS chart] fifteen different species of mammal plus cows, besides humans (and, of course, our little dinosaurs, the chickens). Not only that, we don’t have even have a theory of how the stuff transmits (outside the milking unit at least). We don’t, for example, know if it’s being tranmitted because cows are fed poultry by-products.

NECSI’s concrete recommendations seem more tailored to SARS-CoV-2 than to H5N1 (perhaps some clever person will write an addendum for CAFOs). However, their general conclusion seems on point:

Standard individual-scale policy approaches such as isolation, contact tracing and monitoring are rapidly (computationally) overwhelmed in the face of mass infection, and thus also cannot be relied upon to stop a pandemic. Multiscale population approaches including drastically pruning contact networks using collective boundaries and social behavior change, and community self-monitoring, are essential.

Together, these observations lead to the necessity of a precautionary approach to current and potential pandemic outbreaks that must include constraining mobility patterns in the early stages of an outbreak, especially when little is known about the true parameters of the pathogen.

It will cost something to reduce mobility in the short term, but to fail do so will eventually cost everything—if not from this event, then one in the future.

Apparently, however, APHIS is constraining the mobility patterns of cattle. But not of people. CDC has nothing today about mobility patterns at all, nor do FDA and USDA. (It is easy to imagine a laid-off undocumented worker infected an entire homeless shelter in Houston or Chicago. It’s also easy to imagine farmers infectiing each ther where farmers gather: Feed stores, cattle sales, and so forth.

Conclusion

NECSI’s Norman et al., in their section on “Naive Empiricism,” warm against fatalism:

[A] common public health response is fatalistic, accepting what will happen because of a belief that nothing can be done. This response is incorrect as the leverage of correctly selected extraordinary interventions can be very high.

Here is a fine example, from — you guessed it — WHO:

Joint WHO/FAO/WOAH risk assessment. Risk to humans still considered low, but obviously the virus seems unstoppable https://t.co/DvsHiZ67bS

— Marion Koopmans, publications: https://pure.eur.nl (@MarionKoopmans) April 27, 2024

It’s not “obvious” at all, because we knocked other flus on the head in the early days of Covid with non-pharmaceutical interventions:

Maybe one of the most important graphs of the pandemic. Human behavior in Spring of 2020 crushed the spread of common pathogens. The idea that nothing can be done about endemic viruses doesn’t hold water. We should remember that with human to human transmission of H5N1 looming. https://t.co/WQPboSi7v2 pic.twitter.com/stTFSfS8BO

— Babak (@ChronicBabak) April 30, 2024

I suppose — [lambert pounds head on desk] — I will have to sally forth and attempt to induce a non-fatalistic attitude int others (after all, we’ve got wastewater testing now, which is good). Go thou and do likewise!

NOTES

[1] I’ve very weak on the clades, the various permuations of H*N*, so I’m not going there in this post. Here, however, is a good long thread on that topic:

2) We would first like to take a step back, and remember that the circulation of H*N* is an ancient story :

Fig. Possible origins of pandemic influenza viruses. Phylogenetic studies suggest that an avian influenza virus was transmitted to humans, leading to the 1918 pandemic pic.twitter.com/nkFSPdIgsX

— Emmanuel (@ejustin46) April 30, 2024

Key sentence: “Phylogenetic studies suggest that an avian influenza virus was transmitted to humans, leading to the 1918 pandemic.” Bird flu has form. It’s not something we want to mess around with or be lackadaisical about, though of course we hope for a good outcome, and not a second pandemic while we’re still suffering from the first.

[2] “CDC is committed to providing frequent and timely updates.” The page is dated April 19. No changes since then. This is, perhaps, the most entertainging of the many “We’re really doing something” bullet points:

• Designing an epidemiological field study and preparing a multilingual and multidisciplinary team to travel on site to better understand the current outbreak, particularly the public health and One Health implications of the emergence of this virus in cattle.

They don’t have their go-bags packed? Why aren’t they on-site already?