I could be put on trial for heresy for saying this…

But I wouldn’t be alone.

You see, saying cap rates don’t matter that much is almost like saying it doesn’t matter how much you pay. Or worse, that “it’s different this time.”

But after making concrete statements in my second book on the cap rate range our firm wants to pay for new commercial real estate assets, I am modifying my opinion to say it doesn’t matter nearly as much as I thought in the past—if you find the right asset.

This brief post explains what I mean.

How did this conversation start?

My third real estate book was published by BiggerPockets Publishing last month. It is called Storing Up Profits – Capitalize on America’s Obsession with STUFF by Investing in Self-Storage.

I also launched a BiggerPockets video series concurrent with the book. The first episode went live recently, and this is one of the first comments I received…

So I’m not sure what he meant about better moderating. Maybe he didn’t like something about my hair, and I understand that.

Or it could have been those glasses. Nah. Bono and I are cool on this.

Well, whatever it is, I understand. Anyway, the second comment is what I want to focus on here. He said self-storage cap rates are notoriously low, and there are far better real estate investment opportunities.

I am not going to argue about the cap rates. They are low. Which means prices are high.

Just like multifamily. And mobile home parks. And industrial. And single-family.

Most real estate assets (well, not malls and retail) are at historically low cap rates, and therefore at notoriously high prices. Let’s explore what that means for a moment, and then I’ll tell you why I don’t think it matters as much as some would say.

What is the cap rate?

I wrote about this in detail in a prior post. The cap rate is like the price per pound when buying meat (or vegetables for you vegans). It’s the value (or price if selling) per dollar of net operating income. Specifically, the cap rate is defined as follows…

Cap Rate = Net Operating Income ÷ Value

So, the cap rate is the unleveraged return on investment. It is the expected unleveraged return on investment for the purchaser. So, for example, if the gross revenue on a self-storage facility is $160,000 annually, and the operating expenses are 38.5%, the net operating income (NOI) is $100,000. If the acquisition price is $2,000,000, the cap rate is $100,000 ÷ $2,000,000 = 5%.

The cap rate is the price per dollar of net operating income. Make sense?

The cap rate has been the standard historic measurement to gauge the value of commercial real estate. Investors will say, “I’m buying this one for a 9% cap rate,” or “I sold it at a 6-cap.” This is shorthand for saying, “I sold an asset that had an unleveraged net operating income of 6% of the sales price.” A 6-cap.

The lower the cap rate, the higher the price. A 5% cap rate property is twice as expensive as a 10% cap rate property. This is because buyers must pay twice as much to get the same income on a 5-cap property as a 10-cap property.

Put more clearly, in a 5% cap rate environment, a buyer will pay $2 million to get an annual income of $100,000. But in a 10% cap rate world, that buyer will only need to pay $1 million to get a $100,000 income stream.

As markets heat up, which we’ve seen since the Great Financial Crisis, cap rates compress. And U.S. cap rates are compressed to record levels right now. Some buyers are acquiring assets at 4% cap rates, some even lower.

Which causes buyers and pundits to say, “The cap rates are too low. I’m not going to invest in this deal.”

Here’s why I now think that is wrong-headed

(Wrong-headed in some cases, at least. But accurate in others.)

The cap rate alone doesn’t consider the operational situation or value-add opportunities.

Here’s what I mean…

In 2016, I published a book humbly titled The Perfect Investment. It described the long view of the demographics and operational dynamics that make multifamily investing an excellent investment opportunity.

I told readers that our company looked for large multifamily assets priced between a 6% and 8% cap rate. Cap rates have compressed a lot in five years since that book. Now multifamily investors are acquiring apartments at cap rates in the 4% to 6% range.

Recall the value formula for commercial real estate:

Value = Net Operating Income ÷ Cap Rate

This is a significant difference. To put this in perspective, an apartment asset with a $200,000 net operating income is valued at $3.33 million at a 6% cap rate. But that same asset with the same income is valued at $5 million just by shifting the cap rate to 4%. That is a 50% increase in value for a two-point cap rate shift in this case.

For most apartments these days, I think that $5 million deal has a good bit of risk built in. Why? Though there are many exceptions, large apartments are generally upgraded these days. Most value-add opportunities are gone since they are typically owned by professional operators. Most properties are fully upgraded and operating well.

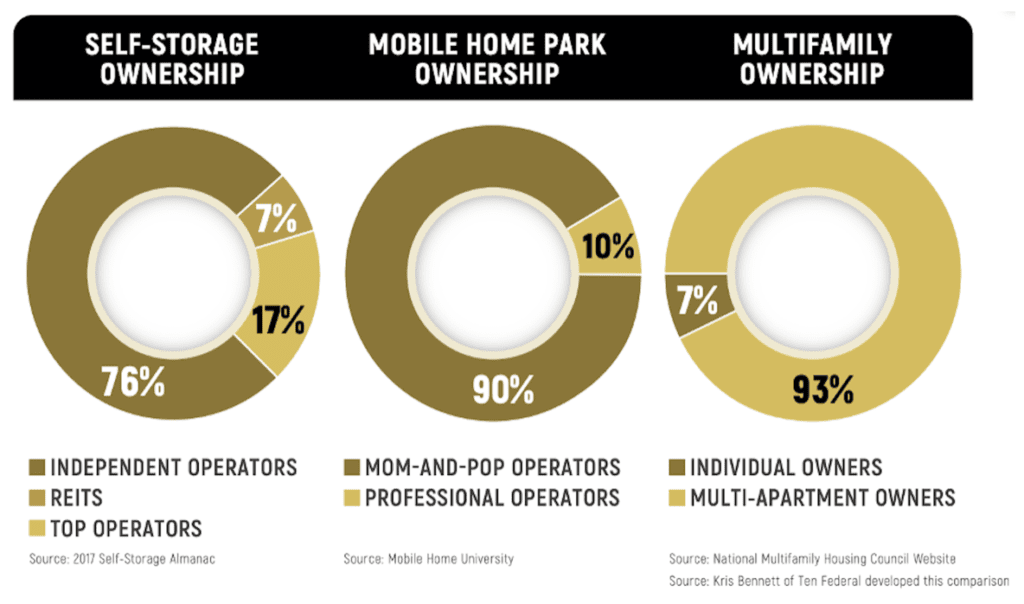

Multifamily has been the darling of commercial asset classes for the past decade. One study says that multi-asset owners own 93% of multifamily assets over 50 units. Professionals who have bled the value-adds out of their assets, leaving little upside for the next buyer other than the hope of income increases from inflation. And hope isn’t a sound business strategy.

If you don’t have a predictable way to increase the net operating income, then you’ll likely be dependent on cap rates staying steady or compressing further. If cap rates expand, property values will decrease.

And if leverage is high, you may find your property underwater. And you may be unable to refinance it. This could be the start of a death spiral. So, in these cases, the cap rate is critical. Most investors shouldn’t buy a fully stabilized property at a severely compressed cap rate.

Operational inefficiencies and value-add opportunities

I said the cap rate alone doesn’t consider the operational situation or value-add opportunities. In the case of a fully stabilized property, like many apartments today, the cap rate may be a good predictor of future ROI performance.

But in the case of poorly managed properties or assets with significant unlocked intrinsic value, the cap rate may be a poor indicator of future ROI performance. Why?

Because the cap rate, at the sale of a property, reflects the value per dollar of NOI, based on the prior owner’s operation. If the previous owner was a poor manager with high costs and less-than-optimized revenues, then the cap rate may only reflect their poor operations. Not your future operations.

BiggerPockets recently published my video on about ten ways to add value to a self-storage property. These value-adds include obvious items like raising rents to market levels, raising occupancy, and reducing delinquency.

But they also include some opportunities to unlock hidden intrinsic value. For example, a mom-and-pop operator may do nothing with a few acres of vacant land while the community experiences a severe under-supply of outdoor boat and RV storage. Or they may utilize their office/showroom only to rent units and sell their kids’ raffle tickets.

A professional operator may buy this facility at a 4.5% cap rate, which may look over-priced to the uninformed observer. But this pro will go to work to increase rates, reduce delinquency, raise occupancy, add boat/RV storage, and sell retail items (locks, boxes, tape, and scissors) from their remodeled showroom. And they sign a contract with U-Haul to lease trucks. Before long, this asset, if acquired at the previous price with the new NOI, would have been north of a 7% cap rate.

This is why cap rates – by themselves – should not be the ultimate indicator of a commercial property’s value and marketability.

One example

My firm invested in a self-storage asset in Texas in 2019. It was acquired for $2.4 million cash from a declining mom-and-pop seller. The prior owner had no internet marketing, bloated expenses, and rents at about 20% to 30% below market. Sixty of its 600 units were seriously delinquent.

Our operating partner quickly developed an online presence, raised rates, fixed delinquency, and added U-Haul leasing. The property appraised for $4.6 million within just four months, and the operator added debt of $2 million, leaving only about half a million dollars in equity in the deal.

The operator sold the property in under two years for $4.6 million. This provided investors with over $2 million in profit plus cash flow over the hold period, resulting in a multiple on invested equity of 4.6x and an IRR of 70.5%. This means that each $100k invested in the project turned into $460,000 in less than two years.

What about a zero cap rate?

I’ve been waiting for the day when we get a zero cap rate deal. This is funny coming from an author who poo-pooed deals under 6% five years ago. A zero cap rate could be a deal that is so badly mismanaged that there is no income at all. High expenses, low occupancy, and low revenue could be symptoms of a deal like this.

This could be a screaming deal for the right operator who knows how to analyze it and turn it around. I know several operators who might love to get their hands on assets like these.

Self-storage can be a profit center!

Are you tired of overpaying for single and multifamily properties in an overheated market? Investing in self-storage is an overlooked alternative that can accelerate your income and compound your wealth.

What asset classes have less cap rate relevancy?

I mentioned the difference between multifamily assets and other asset types at this time. Kris Bennett, a self-storage guy, did the following analysis:

Note that 76% of self-storage assets are owned by independent operators. About 2/3rds of these are owned by mom-and-pop operators, who only have one facility. Mom-and-pops own even a higher percentage of mobile home parks at up to 90%.

I get nervous when looking at stabilized multifamily (or any other class) deals in the 3% to 4% cap rate range. But when I look at unstabilized self-storage or mobile home parks in this same range, I want to know the story behind the cap rate. For those that are poorly managed with lots of unlocked intrinsic value, I look for a potential deal with high projected ROI.

So what about you? Do you think I’m a heretic? Or do you want to find your own unstabilized mom-and-pop commercial asset? Whether you’re an active operator or a passive investor, I can’t think of a better strategy to create safety and investor value.

What about you? Do you agree that the cap rate is often irrelevant? Have you found assets that support this premise, or is the author out to lunch?