Renters may deserve as much disclosure when it comes to electricity bills as homeowners, but many are left in the dark.

One in five households said they gave up basic necessities to pay an energy bill for at least one month during 2020, and some reported that they had kept their home at an unsafe temperature, the U.S. Energy Information Administration said. Gas NG00, +0.77% and power market volatility tied to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, on top of an inflationary economic rebound, isn’t helping with those costs.

For renters, many of whom have no idea how inefficient the heating, cooling and appliances in their apartment or house might be when they sign a lease, these unforeseen costs can leave them on edge. Rental units consume 15% more energy per square foot than owner-occupied homes in the U.S., according to the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE).

Only a few cities in the United States require building owners to disclose energy information to renters, and none require disclosure at the time of listing.

But ACEEE believes that energy-efficiency transparency up front will help shape which rentals tenants opt for. That, in turn, would light a fire under landlords to install more energy-efficient features in their property, including less-wasteful dishwashers or electric heat pumps.

“On average, renters were willing to increase their monthly rent by 1.8% for each one-unit increase in a listing’s energy score, which would translate into more than $400 of additional annual revenue for landlords for an average-priced rental unit.”

“How can renters possibly make informed decisions about which home to live in without being able to compare what their utility bills will be?” said Reuven Sussman, director of the behavior and human dimensions program at ACEEE. The group has just concluded an experiment to see how efficiency data impacted rental selection.

“Our experiment showed that if renters have that energy cost or efficiency rating, it’s absolutely going to affect their choices. It may also nudge landlords to make their buildings more efficient,” said Sussman.

Read: Looking to buy a house? Builders are betting you’ll have to rent instead

Energy efficiency earned more clicks

To prove its point, ACEEE created a mock rental search site to gauge would-be renters’ selection behavior when they were given more and less information on how efficient a given listing was. About 2,400 participants were unknowingly tested for their reaction when a listing made clear high efficiency ratings or low energy costs. The same images were rotated through the test to reduce the potential for the photos to influence choice.

Study participants “searched” for a home, specifying preferences including location, property type (house or apartment), number of bedrooms and monthly rent. They were then shown three search results at a time and asked to select the rental unit they liked the most within each set.

ACEEE

Some participants saw information about the units’ energy efficiency, presented in one of six possible formats, while those in a control group saw no energy information, true to how current listing sites look.

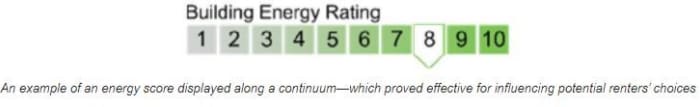

When energy labels were present, renters selected the most efficient listings 21% more often than when energy efficiency information was hidden, the study found. On average, renters were willing to increase their monthly rent by 1.8% for a one-unit increase in energy score (on a scale from 1 to 10), which would translate into more than $400 of additional annual revenue for landlords for an average-priced rental unit.

How the energy-efficiency scores were presented mattered, too. The study found that showing an energy rating along a continuum or simply as a score out of 10 — helping renters understand how each unit compares to the best and worst homes — is more effective.

ACEEE

Energy use in residential buildings accounts for about 20% of U.S. carbon emissions, Energy Department data show. And ACEEE estimates that energy-saving measures just among households have the potential to reduce emissions by 33% by 2050.

Efficiency will also be vital to reduce the strain on the U.S. power grid, a system in need of upgrades and one expected to be hit by increased use as more vehicles go electric TSLA, +1.25% and more homes are heated with electric systems over natural gas NG00, +0.77% and heating oil.

Lower incomes, greater cost

Rental numbers are not insignificant. Renters headed about 36% of the nation’s 122.8 million households in 2019, the last year for which the U.S. Census Bureau has reliable estimates. In all, young people, racial and ethnic minorities, and those with lower incomes are more likely to rent.

Renters skew to the lower ends of income and wealth distributions, according to data from the Federal Reserve’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances. About three-fifths of people in the lowest income quartile (60.6%) rent their homes. The opaque information around energy bills is a particular challenge for low-income households who also pay a higher percentage of their income on energy bills.

There’s also no opportunity to spread energy bills among earners when you live alone. Though renter-occupied households are almost evenly split between families (50.4%) and non-families (49.6%), people living alone account for the biggest single group of renters (38.1%).

“‘By reducing utility costs and improving building conditions, energy efficiency upgrades… boost the building’s property value.’ ”

For now, most renters have little power to make energy-saving changes to their homes, nor do most want to spend on the upgrades themselves. They can swap lightbulbs, use plastic sheeting on windows, or try to remember to shut off the lights when they leave a room, but these aren’t the kind of moves to net significant savings.

Landlords typically don’t pay those utility bills, so their incentive for upgrades is low, unless they can turn those changes into a better investment and know that they too are working toward broader climate-saving goals, factors that ACEEE believes should be stressed more.

It’s just this language that could sway landlords, improving their investment, attracting more reliable tenants, and making a dent in the affordable-housing shortage, agrees Oriya Cohen, writing for the Urban Institute Initiative.

“By reducing utility costs and improving building conditions, energy efficiency upgrades increase a building’s net operating income, boost the building’s property value, and ultimately expand the building owner’s access to capital,” Cohen says. “These additional resources better position building owners to preserve the affordability of their units.”

Sussman and the ACEEE hope that the economic and climate incentives bring change at the municipal level, perhaps demanding a labeling policy.

If so, landlords would be required to hire a certified assessor to do an audit of the apartment before it goes on the market. It’s a service that some local utilities already partially or fully cover.