The almost 1,000 companies that have opted to pull out of Russia following its unprovoked invasion of Ukraine are not just benefiting from a reputational boost. They are also being rewarded by financial markets, while those who remain behind are being punished.

That’s according to a new report from Yale Professor Jeffrey Sonnenfeld and his research team at the Yale School of Management. The team has been monitoring almost 1,300 companies that do business in Russia and has kept a list to highlight the decisions companies have made about staying or leaving since the start of the war on Feb. 24.

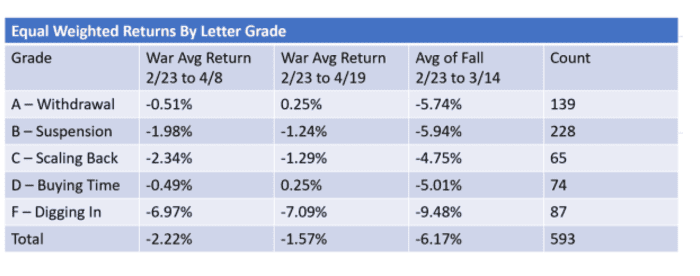

“We find that equity markets are actually rewarding companies for leaving Russia while punishing those that remain behind, with divergent stock performance generally corresponding with the degree of Russian exit — which holds true across regions, sectors and company sizes,” reads the Yale report.

What’s more, the focus on asset write-downs and lost revenue from Russia is misplaced. “We demonstrate that the shareholder wealth created through equity gains have already far surpassed the cost of one-time impairments for companies that have written down the value of their Russian assets,” asserts the report.

“‘Clearly, doing well has not been antithetical to doing good — at least when it comes to withdrawing from Russia.’”

The Yale list is divided into five categories assigned grades A to F, with the latter letter being attached to companies that are “digging in,” or defying public calls to exit. There are now 29 U.S. companies in that category, although the situation remains highly fluid as corporate executives offer updates on their plans.

Background: Yale professor monitoring companies still doing business in Russia ups the ante by highlighting those that are now ‘digging in’

The other four categories are A, the grade for “withdraw,” which describes those companies making a clean break from Russia; B for “suspension,” for companies that are temporarily curtailing activities, while keeping their return options open; C for “scaling back,” or reducing some activities while continuing others; and D for “buying time,” for companies that are holding off on new investments in Russia, and in many cases closely aligned Belarus, while continuing most business there.

For the full list of companies: Visit the Yale School of Management website

The report measures total shareholder returns at those companies that have exited Russia relative to those that have stayed. Researchers used Feb. 23 as their start date as that, in the U.S., marked Russia’s launch of its overnight, full-scale invasion.

The Yale team used two end dates. The first was market close on Aril 8, as that offered a cutoff point before the start of first-quarter earnings season. That allowed the report to exclude the many other macro factors that were showing up in earnings, such as supply-chain snags and inflation, issues that led many companies to lower their analyst guidance.

The second was through market close on April 19, to provide the data set a full eight weeks from the start of the invasion. As an extra check, the report measured a third time period of Feb. 23 to March 14, to track the steep selloff that came immediately after Russia invaded.

Companies were organized based on the five categories of the list and were measured using a market-capitalization-weighted method, and an equal-weighted method, as the following tables illustrate:

Source: Yale School of Management

Source: Yale School of Management

The findings indicate that those companies with higher grades are clearly faring better than those with grades D and F. The market-cap weighting is likely a more accurate representation of category performance, as it reflects actual financial markets more closely, giving larger companies a greater weighting than smaller ones, the researchers noted.

“The pattern of F companies underperforming generally aligns with our anecdotal observations from updating the list in real-time,” they wrote.

From the time the list had its first airing on CNBC on March 7, many of the companies that had been identified as remaining in Russia suffered stock declines of 15% to 30%, even as key market indices were down just 2% to 3%.

See also: Opinion: Globalization failed for emerging markets. And now deglobalization will be put to the test

On the other side of the equation, the report also found that asset write-downs and lost revenue from pulling out of Russia were far exceeded by market-cap gains — including in some of the biggest cases.

At least six multinationals that booked significant write-downs — Heineken HEIA, +1.26% HEINY, +2.44%, Shell SHEL, -0.65%, Exxon XOM, -0.17%, Carlsberg CARL.B, +0.40%, AB InBev ABI, +1.64% and Société Générale GLE, +0.10% — have seen far more wealth created than has been destroyed in aggregate.

“Perhaps even more surprisingly, each of these companies had positive stock performance after the announcements of their exits from Russia and the values of their asset write-downs — after their stocks initially tanked in the period leading up to their announcement in most cases, as shown by the negative ‘war returns,’ ” the report states.

Those six companies incurred asset write-downs of over $14 billion but have generated nearly $39 billion in subsequent equity gains.

The report found that the gains enjoyed by companies that have curtailed their activities in Russia extend beyond public equity markets into credit markets, as measured by longer-dated corporate bond prices, credit spreads and related derivatives.

“Our sweeping analysis of global capital flows demonstrates the importance investors attribute to the decision to withdraw from Russia — and that investors believe the global reputational risk incurred by remaining in Russia at a time when nearly 1,000 major global corporations have exited far outweigh the costs of leaving,” says the report.

“Clearly, doing well has not been antithetical to doing good — at least when it comes to withdrawing from Russia.”

The Yale list has acted as a catalyst spurring companies into action, starting with about 12 that announced plans to fully withdraw from Russia immediately after the invasion of Ukraine. That number jumped to 70 over a single weekend in March. Since then, the list of leavers has steadily climbed to almost 1,000 in late May, and includes McDonald’s Corp. MCD, +0.44%, which has sold its entire Russia business to a local investor.

See: McDonald’s exit from Russia puts growth plans in disarray, analyst says

“The McDonald’s move was both symbolic and substantive,” Sonnenfeld told MarketWatch. “It was there since 1990 as almost a first anchor tenant, and a real flagship because of the global branding value.”

The fast-food giant’s exit “sent shock waves over the bow and surprised the big beverages companies, because McDonald’s is a leader,” he said.

Sonnenfeld has argued that sanctions are designed to bring the Russian economy to a standstill, as a way of helping Russians understand that their government’s attack on Ukraine is making the country an international pariah, and to spur them to push for change. Such measures require that companies voluntarily add their support to shore up efforts made by governments and international bodies.

There’s also the risk to companies that have not exited Russia operations of being boycotted by younger people, who as both prospective customers and employees are carefully attuned to corporate values and are quick to take action when they are disappointed.

“Business leaders are rewarded for speaking out,” Sonnenfeld said. “They’re the most ascendant set of institutional leaders in the world. Military leaders don’t have a voice.”