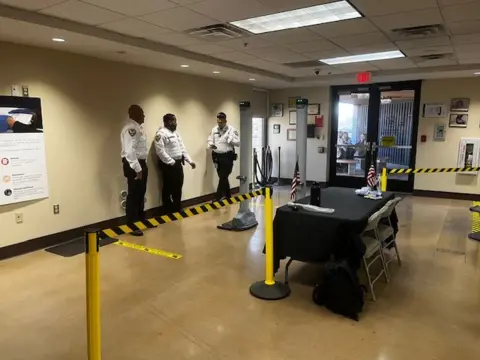

Razor wire. Thick black iron fencing. Metal detectors. Armed security guards. Bomb sweeps.

The security at this centre where workers count ballots mirrors what you might see at an airport – or even a prison. And, if needed, plans are in place to further bolster security to include drones, officers on horseback and police snipers on rooftops.

Maricopa County became the centre of election conspiracy theories during the 2020 presidential contest, after Donald Trump spread unfounded claims of voter fraud when he lost the state to Joe Biden by fewer than 11,000 votes.

Falsehoods went viral, armed protesters flooded the building where ballots were being tallied and a flurry of lawsuits and audits aimed to challenge the results.

The election’s aftermath transformed how officials here handle the typically mundane procedure of counting ballots and ushered in a new era of high security.

“We do treat this like a major event, like the Super Bowl,” Maricopa County Sheriff Russ Skinner told the BBC.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe county, the fourth most populous in the US and home to about 60% of Arizona’s voters, has been planning for the election for more than a year, according to Skinner.

The sheriff’s department handles security at polling stations and the centre where ballots are counted. The deputies have now been trained in election laws, something most law enforcement wouldn’t be well-versed in.

“Our hope is that it doesn’t arise to a level of need for that,” he said when asked about beefed-up security measures like drones and snipers. “But we will be prepared to ensure that we meet the level of need, to ensure the safety and security of that building” and its employees.

The election process here in many ways echoes that in counties across the country. Ballots are cast in voting locations across the county and then taken to a central area in Phoenix where they’re tabulated. If they’re mailed in, the ballots are inspected and signatures are verified. They’re counted in a meticulous process that includes two workers – from differing political parties – sorting them and examining for any errors.

The process is livestreamed 24 hours a day.

While much of this process remains the same, a lot else has shifted. Since the 2020 election, a new law passed making it easier to call a recount in the state. Previously, if a race was decided by the slim margin of 0.1% of votes cast, a recount would take place. That’s now been raised to 0.5%.

The tabulation centre is now bristling with security cameras, armed security and a double layer of fencing.

Thick canvas blankets cover parts of a parking lot fencing to keep prying eyes out. Officials say the canvas was an added measure to protect employees from being harassed and threatened outside the building.

“I think it is sad that we’re having to do these things,” said Maricopa County Supervisor Bill Gates.

Gates, a Republican who says he was diagnosed with PTSD after the election threats he received in the 2020 election, doesn’t plan to run for office again once this election is over because of the tensions.

“I do want people to understand that when they go to vote centres, these are not militarised zones,” he told the BBC. “You can feel safe to go there with your family, with your kids and participate in democracy.”

The county has invested millions since 2020. It’s not just security, either. They now have a 30-member communications team.

A big focus has been transparency – livestreaming hours of tests for tabulation machines, offering dozens of public tours of their buildings and enlisting staff to dispute online rumours and election conspiracies.

“We kind of flipped a switch,” assistant county manager Zach Schira told the BBC, explaining that after 2020 they decided, “OK, we’re going to communicate about every single part of this process, we’re going to debunk every single theory that is out there.”

It’s all led up to Tuesday’s election.

“We may be over prepared,” Sheriff Skinner said, “but I’d rather prepare for the worst and hope for the best.”

Some Maricopa Republicans told the BBC they’ve tracked recent changes and felt there would be fewer problems this election cycle.

“They’ve made steps that I think will help,” said Garrett Ludwick, a 25-year-old attending a recent Scottsdale rally for Trump’s vice-presidential running mate JD Vance.

“More people are also aware of things now and I think there are going to be a lot of people watching everything like a hawk,” he said, wearing a Trump cap that read, “Make liberals cry”.

One Republican voter, Edward, told the BBC the 2020 cycle caused him to get more involved. He’s now signed up for two shifts at polling locations in Maricopa County on Tuesday.

“Going to a rally or being upset isn’t going to fix things,” he said. “I wanted to be part of the solution.”

Not all are convinced.

“I still think it was rigged,” said Maleesa Meyers, 55, who like some Republican voters said her distrust in the process is too deep-rooted to believe the election could be fair. “It’s very hard to trust anyone today.”

Results in Arizona often hinge on Maricopa County, giving the county an outsized role in the outcome. Officials here estimate it could take as long as 13 days to count all ballots – meaning the expected tight race in this swing state might not be called on election night.

“There’s a chance that in 2024, the whole world will be watching for what the result is in Maricopa County,” said Schira, the assistant county manager.

“Truly the world’s confidence in democracy could come down to this.”