Yves here. Wolf does the very important service of showing that (so far) the Bank of England intervention in the gilts market is much smaller than the press reports would lead you to believe. However, there’s also a lot of consternation as to why the Bank is engaging in easing in the midst of a tightening cycle.

In fairness, it’s not as if the Bank had any control over the recklessly stimulative and wealthy-enriching Truss/Kwarteng mini-budget that set gilts into a mini-meltdown. The Bank is also contending with aggressive interest rate increases by the Fed, which puts other central banks in the position of importing inflation (via further currency depreciaition) if they don’t keep pace. The Bank also may not have been sufficiently cognizant that British pension funds took greedy leveraged positions and were wrongfooted. If the UK is much like the US, large pension funds are close to unregulated so it’s not as if they can be prevented from running lemming-like into dodgy fads.

And the Bank relying (again so far) more on posturing and not as much as expected on actual buying does show some finesse. We’ve seen this sort of thing sometimes in central bank responses to crises, with a noteworthy version when Mario Draghi calmed rattled investor nerves by announcing the OMT…which amounted to nothing new, but was merely a rebranding of existing authorities.

I hope to give this a longer-form treatment, but the short version is that QE is not a form of monetary stimulus that is directed at the real economy. Its role in the financial crisis was to allow central banks to manipulate the longer end of the yield curve, as well as (in the US case) lower the spreads of high quality mortgages over Treasuries. That helped shore up housing prices and also indirectly provided some economic stimulus by facilitating refis.

However, generally speaking, particularly for QE directed at government bonds, QE is an asset swap. It’s not as if retail bond holders are going to tender bonds in QE. And the professional investors that do won’t and can’t run out and use the cash they get on real economy spending. They’ll go buy other financial assets. So QE does not stimulate the real economy much if at all, but does goose asset prices, which has in the long run distorted the capital markets (unnaturally high asset prices promote speculation rather than real economy investment).

Mind you, I do not want to sound as if I am praising the Bank of England. Raising interest rates is a lousy way to handle inflation cause by supply shocks, significantly Covid-induced labor shortages, Ukraine-sanctions-induced energy price increases, and food inflation. QE is a bad policy that central banks adopted uncritically, copying the Fed. I am merely saying the Bank of England handled this particular nasty juncture better than it appears….but that’s not saying all that much. It remains true that the combination of policies is confusing to investors when central banks are big believers in managing expectations.

By Wolf Richter, editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

The Bank of England announced on September 28 that it would buy up to £5 billion per day in long-dated government bonds “to help restore market functioning and reduce any risks from contagion.” This was hugely ballyhooed as a “pivot” on the internet and in the US financial media. Yesterday it came out with an even more hugely ballyhooed announcement that it would double its potential bond purchases to £10 billion per day for the rest of the week. And today, it came out with an even more hugely ballyhooed announcement that it would “expand” the bond purchases. Throughout it maintained that it would “cease all gilt purchases” on Friday, October 14.

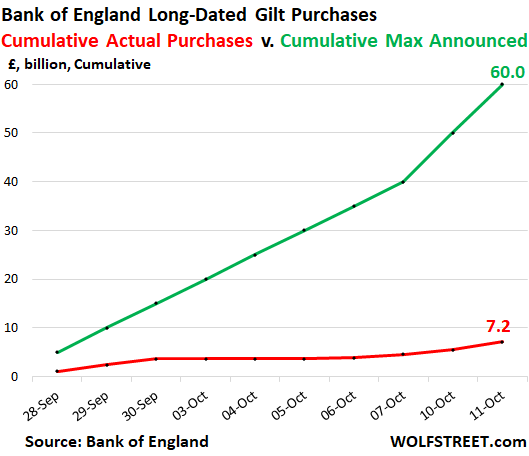

And yet, despite all the hoopla, the BOE has actually bought just a small fraction of the bonds that it said it might buy. In total, since September 28, the were 8 days of “up to £5 billion” per day in purchases and 2 days of “up to £10 billion” per day, for a total of £60 billion.

And yet… through today, it purchased only £7.2 billion in total over the entire 10-day period, with four days of zero or near-zero purchases. It purchased only 12% of the amounts it said it might purchase.

The chart shows the huge and growing gap between its cumulative purchases (red line) and its cumulative announced potential purchases (green line). The actual purchases were in effect minimal so far:

The BOE is caught between 10% inflation it needs to crack down on with big rate hikes and lots of QT and a crisis over derivatives that leveraged UK pension funds blew their brains out with.

The relatively puny amounts of actual purchases show that the BOE is trying to calm the waters around the gilts market enough to give the pension funds some time to unwind in a more or less orderly manner whatever portion of the £1 trillion in “liability driven investment” (LDI) funds they cannot maintain.

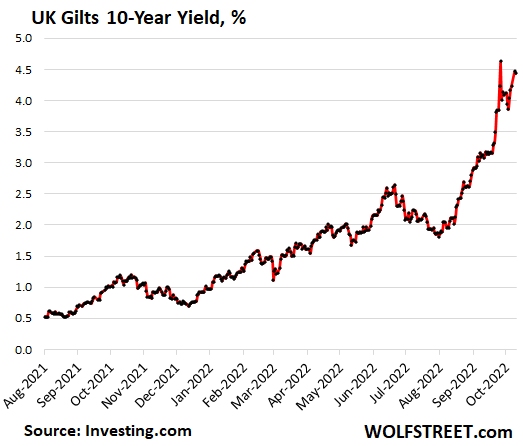

The small scale of the intervention also shows that the BOE is not too upset with the gilts yields that rose sharply in the run-up to the crisis, triggering the pension crisis, and have roughly remained at those levels. The 10-year gilt yield today at 4.44% was roughly unchanged from yesterday and just below the September 27 spike peak.

And it makes sense to have these kinds of yields in the UK, and it would make sense for these yields to be much higher, given that inflation has spiked to 10%, and yields have not kept up with it, nor have they caught up with it. And to fight this raging inflation, the BOE will need to maneuver those yields far higher still:

So today, BOE Governor Andrew Bailey, speaking at the Institute of International Finance annual meeting in Washington D.C., warned these pension fund managers that the BOE will only provide this level of support, however little it may be, through the end of the week, to smoothen the gilt market and give the pension funds a chance to unwind in a more or less orderly manner the portions of their LDI funds that they cannot maintain.

“My message to the funds involved and all the firms is you’ve got three days left now,” he said “You’ve got to get this done.”

The Wall Street hype organs and trolls had been swarming all over the internet and the media, trumping up the BOE’s “pivot,” and that the Fed would pivot next, and yada-yada-yada. So now, the BOE not only didn’t pivot, confirming what it had said all along, but also dished up an ultimatum to the pension funds.

The BOE has been in communications with the pension funds, and with the investment banks that sent out the margin calls to the pension funds, since before the crisis erupted into public view. So we can assume that the pension funds and investment banks have known about the finality of the bond purchases, that the end-date as announced on September 28 would stand, though they lobbied hard for extending it through the end of October. Bailey’s message today surely is no surprise to them.

But it was a surprise to the stock markets in the US that were still dreaming about the wondrous BOE pivot that would be the precursor of the Fed pivot or whatever.