Yves here. Yours truly does not much watch the ponies since there are so many analysts and commentators that do so. But to remind readers, big stock market crashes do not kick off broad financial crises unless a lot of those positions are funded by debt. The post Great Crash reforms in the US limited margin lending, even though there have been some efforts to skirt those rules, such as equity derivates, like the total return swaps that cratered Archegos.

Sadly, it was Greenspan that put the Fed in the business of thinking its job was to protect equity investors. As the Wall Street Journal exposed in 2000, Greenspan was obsessed with what determined the level of stock prices. He did point out in 1996, just as the dot-com mania was starting that the market seemed to be suffering from irrational exuberance. When the Dow did a swan dive, he quickly retreated and talked the markets back up.

We pointed out in ECONNED how Greenspan’s stock market obsession played a role in stoking the financial crisis. After the dot-com bubble collapsed, Greenspan convinced himself it would have a serious real economy impact even though the 1987 plunge had demonstrated the reverse. Greenspan lower policy rates to negative real interest rate level and held them there for a full nine quarters, when the Fed’s practice before had been to drop rates that low only for a quarter in recessionary times. That in turn led investors to scramble for high-yield products. We explained long form how that fed demand for confections like asset-backed CDOs, which consisted largely of the riskiest tranche of subprime mortgage securities.

As Wolf (and even the Wall Street Journal yesterday) points out, investor enthusiasm for stocks appears unabated. One issue is that the averages are unduly influenced by the high prices of super sized tech stocks like Apple, Meta, Google and Microsoft. Nevertheless, stocks overall look to be pretty richly valued, using Tobin’s Q ratio as the measure:

It is finally worth remembering that even though the dot-com bubble seemed to be awfully long in tooth, it had a spectacular blowout phase before it went into reverse. There the trigger was an unexpectedly weak earnings report by bellweather Cisco.

By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

Nvidia, the poster boy of the stock-market mania around Ai and semiconductors, plunged 9.5% in regular trading. In afterhours trading, it dropped another 2.6% to $105.40 a share, for a total drop of 11.7%. The afterhours drop came after Bloomberg reported that the DOJ had sent subpoenas to Nvidia, in an escalation of the ongoing antitrust investigation.

“Antitrust officials are concerned that Nvidia is making it harder to switch to other suppliers and penalizes buyers that don’t exclusively use its artificial intelligence chips,” Bloomberg said, citing its sources.

Nvidia’s market capitalization – which is important because it’s so huge – plunged by $279 billion in regular trading, the most ever lost in one day by one company. Including afterhours trading, it plunged by $342 billion, or by half a Tesla.

But it’s not a big deal because easy-come, easy-go, and Nvidia had similar one-day moves on the way up. The stock is now down 20% from its July 10th peak. And Nvidia wasn’t the only one.

The semiconductor bloodletting during regular hours included:

- Nvidia [NVDA]: -9.5%

- Intel [INTC]: -8.8%

- Marvell Technology [MRVL]: -8.2%

- Broadcom [AVGO]: -6.2%

- AMD [AMD]: -7.8%

- Qualcomm [QCOM]: -6.9%

- Texas Instrument [TI]: -5.8%

- Analog Devices [ADI]: -6.5%

- ASML [ASML]: -6.5%

- Applied Materials [AMAT]: -7.0%

- Micron Technology [MU]: -8.0%

- NPX Semiconductors [NXPI]: -7.9%

- KLA [KLAC]: -9.5%

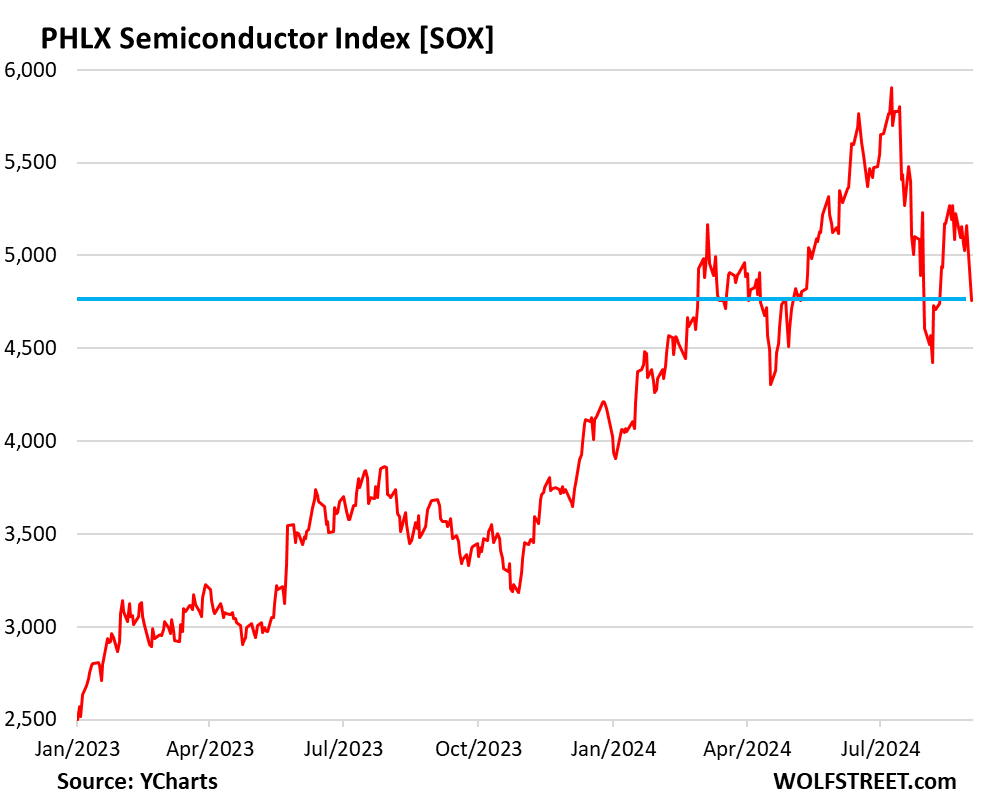

The VanEck Semiconductor ETF [SMH] plunged 7.5%, the biggest one-day drop since the March 2020 crash. The PHLX Semiconductor Index [SOX] plunged 7.8%. So that was a good day’s worth of work on the first trading day of September:

It wasn’t any kind of economic news, such as the sudden collapse of the consumer over Labor Day or the toppling of three big banks on Friday evening or the prediction by AI that the world would end, or whatever, that sank semiconductor stocks – and to a lesser extent stocks more broadly, with the S&P 500 down 2.1% today and the Nasdaq Composite down 3.3%. Instead of collapsing, consumer are doing just fine, and they went back to the punchbowl for refills.

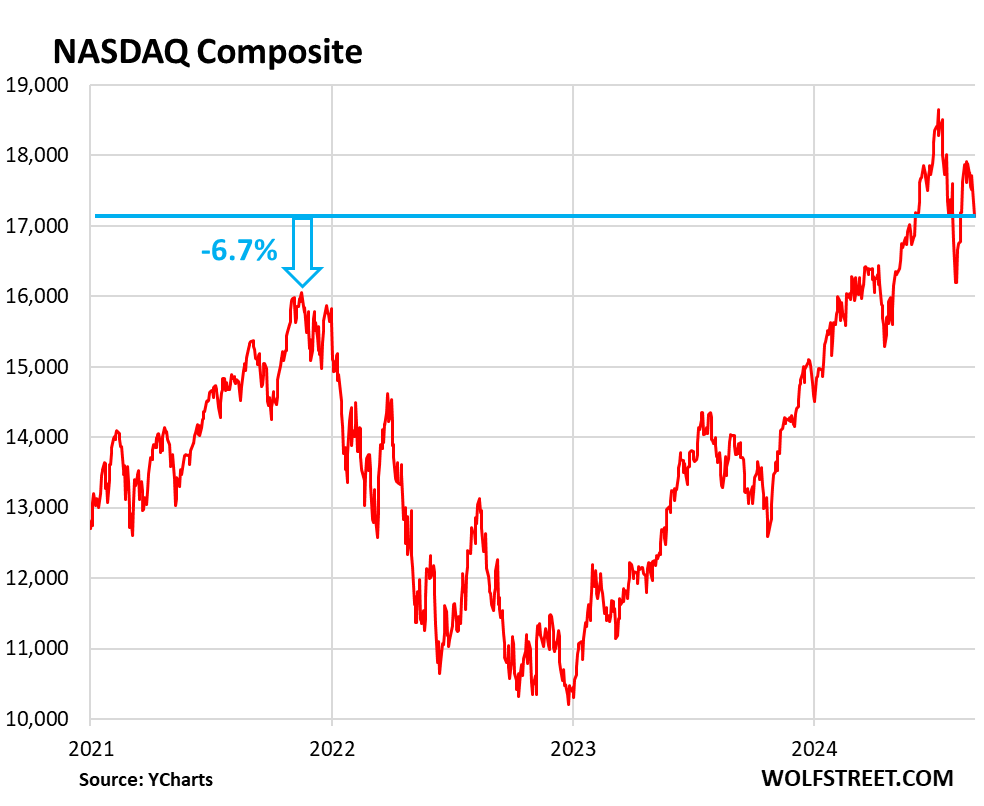

So the Nasdaq composite dropped by 3.3% today to 17,136 and is down 8.1% from its all-time high on July 10.

If it drops another 6.7%, it’ll be back where it had first been in November 2021, with a big sell-off and a generational rally in between. T-bills did better than that since November 2021, but without all the fun and drama.

The action since the July 10 peak is not a good sight:

It’s just that Americans have been more bullish than ever on stocks, after years of huge rallies to where household allocations to stocks as a share of their financial assets reached record highs of 42% in Q2, easily surpassing the then-record of 37% in Q2 2000, according to JPMorgan estimates cited by the WSJ.

Q2 2000 was of course when stocks had begun the Dotcom Bust that would eventually take the S&P 500 down by 50% and the Nasdaq Composite by 78% over the next two-and-a-half years, after which it took the Nasdaq 13 years, including years of QE and 0%, to surpass its Dotcom Bubble high.

But investors consider this now irrelevant. Not going to happen again. Stocks will always go up. The Fed will restart QE every time shares dip a little, etc., etc. With investors so overexposed to stocks, especially to the biggest hottest stocks with ridiculous valuations, such as Nvidia, and overconfident that stocks will always rise, if then something twitches and the selling pressure suddenly surges, then there aren’t enough hardy souls left still willing to buy at these ridiculous prices, and the next layers of buyers – the dip buyers – will have to be enticed with even lower prices. But that has been a rough sport recently.