The first wave of electric micromobility was shepherded by the (still largely unprofitable, bless them) shared micromobility companies — the Limes and Birds of the world that popularized electric scooters. Now, as gas prices surge, the world burns and more people consider traveling to and from work in a way that’s cheap, sustainable and fun, sales of electric scooters are seeing an uptick.

The global e-scooter market size, which was at around $20.78 billion in 2021, is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 7.8% from 2022 to 2030, according to one study. Given that massive market opportunity, private e-scooter startups are coming out of the woodwork with all sorts of neat little contraptions that fold and whiz and alert riders to impending danger.

I know what you’re thinking. Surely the market is already saturated, and the big dogs at Okai and Segway have already got it covered. But Oscar Morgan, co-founder and CEO of U.K.-based e-scooter startup Bo Mobility, says the industry has been coming at scooter manufacturing all wrong.

“The way scooters have grown up was they took the micro-scooter, and they strapped a lithium ion powertrain to it,” Morgan told TechCrunch. “That’s almost like if Tesla had said, we want to do an electric car, so we’ll strap an electric motor to a Model T Ford.”

Bo launched in Amsterdam in early June at the Micromobility Europe event, but the startup will sell its first scooters in the U.K. The founders all come from automotive and engineering backgrounds. Morgan and co-founder Harry Wills met at Williams Advanced Engineering, where they both worked on programs to deploy Formula One technology into other products and categories. Luke Robus, Bo’s other co-founder, used to work on autonomous cars at Jaguar Land Rover’s advanced design studio. Given their expertise, the team thought it would be best to build a scooter like a car — with a fully integrated chassis.

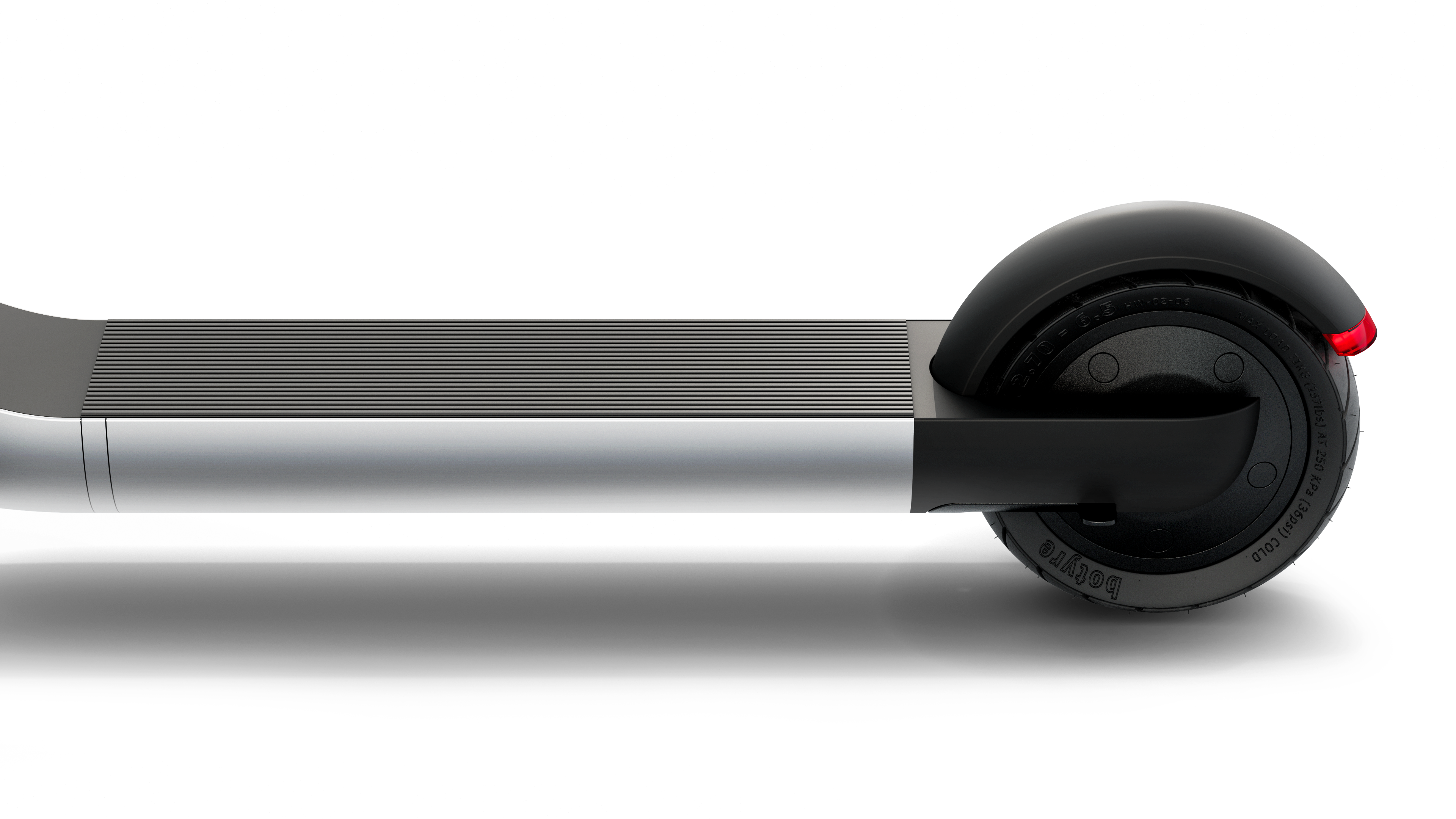

Bo’s scooter is designed with a fully integrated, monocurve chassis. Image Credits: Bo Mobility

Bo’s re-engineered chassis uses a “monocoque” construction technique, which is also referred to in the industry as a structural skin, and it means all of the stresses and loads are supported by the scooter’s external skin across a larger cross section than normal tubular or box scooter frames, said Morgan. Bo refers to it as a “monocurve” because the scooter’s aluminum body has a constant curve from top to bottom. Notably, this means it doesn’t fold, something Morgan said was a conscious decision to maintain structural and ride integrity. But at 40 pounds, it’s light enough to carry easily up some stairs.

“Changing this method of manufacture does not make the product cheaper, but it makes it an order of magnitude stronger,” said Morgan, noting the monocurve also enables Bo to seamlessly package a new generation of stabilization and IoT tech into the scooter. “There’s an old saying that if you’re strategically strong, the tactics don’t matter. And as a fundamental layout, moving from this tubular construction to a true Monocurve, it’s strategically the best way to manufacture these products, certainly at the premium level.”

And premium the Bo scooter is. The startup is currently taking preorders at around $50 (£40), but the sale price will be about $2,435 (£1,995). Non-committal riders can also get their hands on a scooter subscription for $84 (£69) per month.

One of Bo’s credences is to build a scooter that prioritizes user experience rather than just a dazzling specs sheet — although with 31 miles of range, a hook on the neck for securing bags and smart features like GPS tracking and anti-theft, OTA updates and Bluetooth, the specs certainly hold their own.

A built-in, retractable hook allows riders to secure bags. Image Credits: Bo Mobility

Bo was founded in 2019 based on the idea that existing scooter hardware has not only failed to unlock the potential of e-scooters, but also has actively blocked many people from feeling safe and secure enough to jump on one. To address this, Bo has created a system called Safe Steer, an active front-wheel stabilization that can counteract the threat of potholes and bumps in the road, to which scooters, with their small wheels, are vulnerable.

“A lot of people claim that they’ve created a safe scooter because they put a new set of tires on it or the deck got slightly wider or some sort of mediocre shit like that,” said Morgan. “What we wanted to do is create a profound step change. So when we stabilize the steering, suddenly people jump on it and from across all demographics, they feel very comfortable, which is profoundly important.”

Another important differentiator for Bo is the lack of suspension, a feature that Morgan says is totally unnecessary for a scooter that goes tops 22 miles per hour. In fact, Morgan went so far as to say suspension in a scooter is heavy, expensive, unreliable, doesn’t work and is the product of companies without a better idea. All you need, he argues, is a long wheelbase, which gives the rider stable and “cruisy” steering, high-quality tires that take up about 80% of normal road noise, and Air Deck.

Air Deck is made with engineered elastomer to absorb shock and provide a smooth ride. Image Credits: Bo Mobility

Air Deck is basically a bit of engineered elastomer that Bo has attached to the deck of the 6-inch-wide, 22-inch-long deck to put some space between the rider and the scooter’s metal.

“It’s like the soles of a [sneaker], so in the same way your Nikes take the heat out of pavement, this eliminates the chatter and the vibration that actually makes the scooter exhausting to ride,” said Morgan. “When you solve that, it’s amazing how much more comfortable the scooter becomes to ride.”

When can you get one?

Bo doesn’t want to be one of those companies that promises and can’t deliver, so it’s doing a soft rollout for a select group of preorders in the U.K.; those people will receive initial units later this year, according to Morgan. The earliest customers, he noted, will provide Bo with direct feedback to help ensure a great product. By early next year, Bo plans to move into mass manufacture and start shipping first to Western Europe in June, and then, in time, to the U.S.

To keep things as green and supply-chain-hell-resistant as possible, Bo is trying to make scooters close to the final customer. That means the initial U.K. units will be manufactured and assembled in the U.K., and initial mass manufacture and assembly will be done in Western Europe, said Morgan, who noted Bo aims to find similar locations in the U.S. as it expands.

Obviously, preorders will help get Bo to production, but the company will need to raise externally, as well. Bo ended an oversubscribed pre-seed round last year and is in the middle of a seed round that aims to raise $4 million, said Morgan.