The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a health alert Thursday notifying clinicians of a US-based cluster of unexplained cases of liver inflammation in young children, which appear to be part of a puzzling international outbreak that now spans at least 10 countries and two US states.

According to the CDC, Alabama has seen nine cases of unexplained liver inflammation—aka hepatitis—in children between the ages of one and six since October of last year. Two of the cases resulted in liver transplants, though no deaths have been reported. Health officials took notice of the unexplained illnesses after a cluster of five cases presented at one children’s hospital in the state last November, with three of those cases involving acute liver failure. The state has since identified four other cases through February, 2022.

According to reporting by Stat News, North Carolina is also investigating two cases in school-aged children, neither of which required transplants.

The unexplained cases join dozens of others from around the world, mostly in children younger than 10 and many less than five. The United Kingdom has tallied 108 cases this year, eight of which resulted in transplants, the UK Health Security Agency reported Thursday. Of the cases, 79 are in England, 14 are in Scotland, and 15 are in Wales and Northern Ireland. Spain has reported at least three cases. France has reported two suspected cases. Israel’s Ministry of Health reported that it is investigating 12 cases. Denmark and the Netherlands have also reported cases.

Puzzling cases

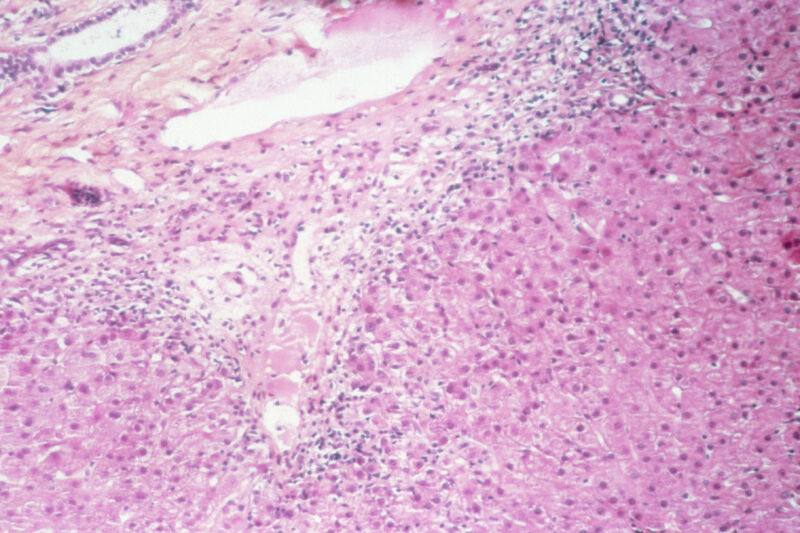

Severe hepatitis is rare in young children, and medical experts worldwide have not yet determined what is causing the liver injuries. The current leading suspect is an adenovirus, though that, too, is puzzling. Of the more than 50 distinct types of adenoviruses known to infect humans, most are associated with common colds and eye infections, though some can cause gastrointestinal and disseminated infections. While there have been reports previously of adenoviruses causing liver inflammation, it’s rare and almost always in immunocompromised children.

Yet, according to early reports, many—if not most—of the children in the current rash of cases were previously healthy. And they’ve consistently tested negative for viruses that are known to cause hepatitis, specifically hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, and E. Though some of the children have tested positive for COVID-19, many have not. And none of the cases in Scotland, where the first cases were widely reported, had received COVID-19 vaccines, eliminating that as a possible cause.

Adenoviruses, meanwhile, have been popping up frequently in the cases. The UK reports that 77 percent of its 108 cases have also tested positive for an adenovirus. And all nine of the cases in Alabama tested positive for adenovirus, too, with five specifically testing positive for adenovirus 41. Health officials in Scotland have speculated that a common adenovirus could be causing more severe disease in some young, immunologically naïve children after they had been restricted from social mixing during the pandemic. But, there’s also the possibility that a new adenovirus has evolved to cause more severe disease.

Still, some experts are keeping an open mind. “Although our investigations increasingly suggest that there is a link to adenovirus infection, we are continuing to look into other potential causes and will issue further updates as the situation develops and we have more information,” Jim McMenamin, head of Public Health Scotland’s health protection division, said in a statement.

For now, the CDC and other health officials advise clinicians to keep a lookout for unusual cases of hepatitis in children and consider testing any such cases for adenoviruses.