Yves here. KLG suggests that important local effects of climate change could persuade skeptics. His introduction:

Anthropogenic Climate Change/Global Warming (AGW) is still denied, by the usual suspects with axes to grind and also by the general population who are often following a lead. One of the most effective approaches may be to identify local consequences of climate change and what this will mean close to home. In this post the visible damage done by accelerating sea level rise in the Sea Islands of Georgia is used as an example. In this case, the damage has been slow in coming but could be on the cusp of palpable acceleration. The local consequences of that are likely to be severe in a shorter timeline than generally assumed. That another chain of similar islands slightly to the west will succeed the current islands will be of little comfort as the people look back on what was wrought by their forebears. Which will probably be their fate, too.

By KLG, who has held research and academic positions in three US medical schools since 1995 and is currently Professor of Biochemistry and Associate Dean. He has performed and directed research on protein structure, function, and evolution; cell adhesion and motility; the mechanism of viral fusion proteins; and assembly of the vertebrate heart. He has served on national review panels of both public and private funding agencies, and his research and that of his students has been funded by the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and National Institutes of Health

The first book-length treatment to my knowledge of anthropogenic climate change/global warming (AGW) for the general reader was The End of Nature (1989) by Bill McKibben. In my view McKibben made his case very well and has continued, for the most part, to do this in his subsequent work. [1] Since 1989, climate change has become noticeable as regions of the earth become deserts, optimal plant growth zones shift into different latitudes and animals regularly appear where they were previously uncommon. Regarding the latter, I grew up at the ocean edge of the Atlantic Coastal Plain of the United States, which is well “below” the “Gnat Line.” I now live in a place that was previously safe from these creatures that make life miserable throughout the summer when the air is still. Now, they are here. Since McKibben and those who have come after, none of these phenomena can be reasonably dismissed by “It’s just the weather.”

So why are so many reluctant to believe that human activities can and do lead to climate change? Such denial could be considered a new thing. Jean-Baptiste Fressoz shows in Happy Apocalypse: A History of Technological Risk (2024) that 18th-century Europeans, especially the French, were well aware that letting technological genies out of their bottles could result in unfortunate consequences. Charles Babbage, inventor of the first functional computer along with Ada Lovelace who was the first computer programmer, wrote in 1835 about the Industrial Revolution:

The chemical changes which thus take place are constantly increasing the atmosphere by large quantities of carbonic acid (i.e., carbon dioxide) and other gases noxious to animal life. The means by which nature decomposes these elements, or reconverts them into solid form, are not sufficiently known. (On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, Quoted from Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming by Andreas Malm).

It is clear that nature does not decompose these elements or reconvert them into solid form on a time scale that “works” for the ecosphere in its current form. Svante Arrhenius, who was a principal founder of the discipline of physical chemistry, published a paper in 1896 (pdf) on what would come to be known as the greenhouse effect caused by the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. His temporal prediction was wrong only because he could not imagine the scale of coal, oil, and natural gas use in the 20th century.

Much of the reluctance to “believe the science” of climate change is attributable to the many Merchants of Doubt who have plied their trade throughout the post-World War II era and continue to be ingenious in their efforts. But there is also the simple fact that climate change is not like the weather. AGW cannot be sensed easily by those not paying close attention to the world around us, especially as we as a society and polity have succumbed to the conceit that the natural world is there for our taking, with necessarily benign consequences.

Sea level rise has been nearest to my concerns about AGW because of where I came from. Despite the gnats (and mosquitoes, deer flies, chiggers, sharks, and venomous snakes on land and in the water), the southeastern coast of the United States from Amelia Island in North Florida to Charleston is a special place. Sir Robert Montgomery of Scotland called the coast of Georgia “The Most Delightful Country of the Universe” (1717) in early “promotional literature” for the colony south of Carolina that became Georgia in 1733. He, never having visited, left out the heat, humidity, bugs and the snakes. But even before the advent of air conditioning, he was not too far off the mark. [2]

The Sea Islands of Georgia [3] are geologically young at less than 10,000 years old. They are constantly changing at their margins due to natural alterations in patterns of water flow from the rivers of Georgia that drain into the Atlantic Ocean and from shifts in the sands where they face the sea. Tidal changes along the Georgia coast are large, ranging from six to nine feet from mean low water to mean high water, twice a day. So natural variation along the beaches from year to year is normal. But overall, these islands have been stable for at least 250 years in their high ground, 8-20 feet above sea level. This can be seen by comparing the maps prepared by John William Gerard de Brahm in the 18thCentury to present maps produced by the US Geological Survey. The smallest of tidal creeks are in the same places de Brahm drew them, even as the sandspits and sandbars shift from year to year.

Nevertheless, according to recent research on sea level rise along the Southeast Atlantic Coast and the Gulf Coast of North America, this stability is not likely to continue. The primary source used here was published in Nature Communications in 2023 (Dagendorf et al.). A more accessible summary was subsequently published by Inside Climate News and later reprinted with permission in The Current [4] on 16 July 2024. I will use some of the data presented in this popular article (which is based on the Dangendorf et al.) as a naïve exercise to illustrate why, in my view, AGW is so often so difficult to appreciate as our most pressing existential [5] threat that is not completely an artifact of politics – local, national, and global.

Mean sea level (MSL) is difficult to measure, but according to Dangendorf et al., MSL has increased approximately 1.5 mm per year since 1900 (~7 inches). This may seem inconsequential, in that (theoretically) when walking along the beach the water would cover your ankles. No big deal. But this increase is unprecedented over at least the last 3000 years.

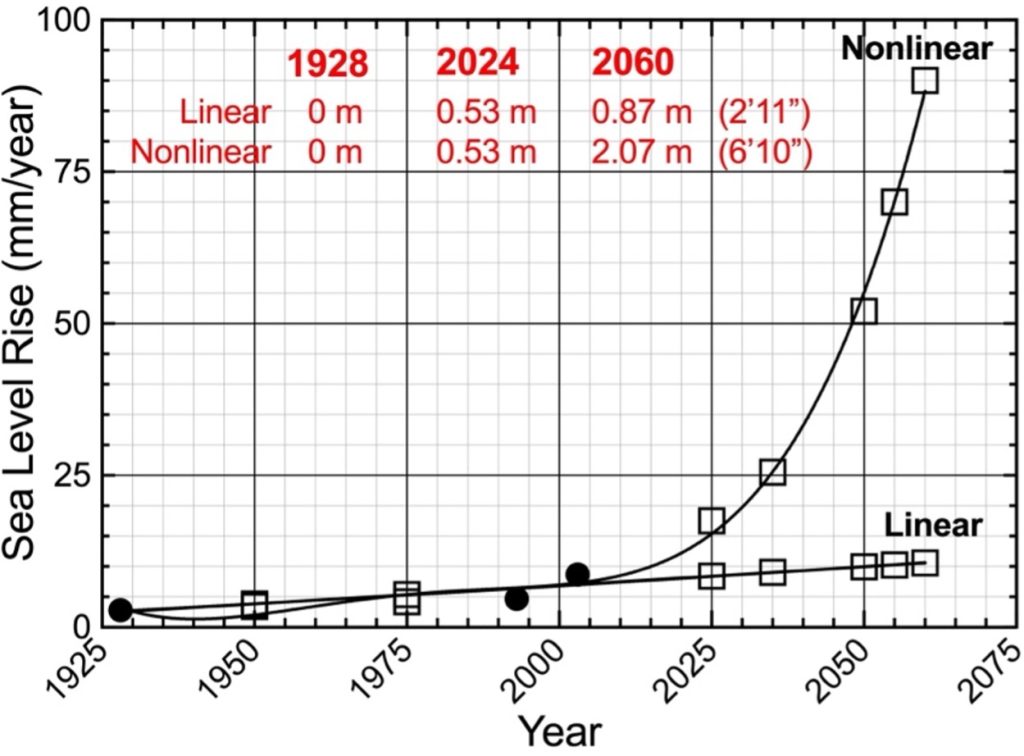

This is not good and is consistent with other correlates of AGW, including the hockey stick graph. Specific measurements from North Florida (70 miles south of Jekyll Island, see below) are illustrated in Figure 1. Measured MSL rise was 2.8 mm/year in 1924, 3.4 mm/year in 1950, and 8.7 mm/year in 2003. This is consistent with the hypothesis that MSL rise in accelerating, with a trajectory more similar to #3 as a first approximation than either #1 or #2, with #1 being the first choice, as if we had one.

If this accelerating increase in MSL is real, then it can be modeled as a nonlinear process. Three points are not enough to fit these data to a curve, but interpolation and moderate extrapolation will allow this, strictly as an illustration, of what may be happening (Figure 2).

At least two key points emerge from Figure 2:

- MSL rise from 1928 through 2024 is essentially the same for both the linear and nonlinear models (~0.53 m/21 inches) but after this MSL rise accelerates quickly.

- By 2060, the nonlinear model predicts a cumulative rise in MSL of slightly more than two meters, or nearly seven feet versus about three feet for the linear model.

This estimate is only an exercise, but it is not too far removed from the moderate-to-large estimates in Dangendorf et al. The nonlinear curve also illustrates a common misconception regarding climate change. One cannot assume a linear relationship for anything, even if MSL rise along the southeastern coast during the past 100 years seems to be consistent with a slow, steady increase, until now.

Feedback loops and forcing mechanisms are common in the natural world, which is anything but linear. As the climate warms, the Greenland Ice Sheet will melt faster. As this freshwater flows into the North Atlantic, disruption of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) and the Gulf Stream can be expected, perhaps sooner rather than later according to a paper published last week in Nature Communications (summarized at this NC link yesterday). Note the protestations from experts that talk of this is “premature” since we don’t know the complete answer, yet. Such doubt is the handmaiden of denial of an unpleasant reality. The collapse of AMOC seems highly likely. When this happens, the sequelae will be grim in the British Isles.

In any case, a 3-foot rise in MSL along the southeastern coast of North America would be unmanageable, whatever the exact timetable. A 7-foot rise in MSL would be catastrophic. Along the coast of Georgia, none of the Sea Islands would be habitable and much of the mainland for 20 miles inland in some places would be marginally habitable. The same is true for most of Florida, especially South Florida, where despite the Resilient Florida Program of Governor Ron DeSantis, nothing can be done to hold back the sea, which in Miami also comes up through the rock.

This brings us to what is seen today in the Sea Islands of Georgia (map at Endnote 3). Tides are higher than before, with novel, playfully named “king tides” occasionally lapping at the edges of the pavement of the elevated causeways leading to the three islands connected to the mainland. This is new. As is the severe erosion of the northern end of Jekyll Island, which has become something of a tourist attraction at the recently named Driftwood Beach. What is generally not understood by visitors and a distressing number of locals is that through the 1980s Driftwood Beach was high ground, where as children my friends and I chased “red-headed scorpions” (actually the skink Plestiodon inexpectatus) in the wooded sand dunes while watching out for snakes and prickly pears. Jekyll has been called the nearest faraway place. It still is, but for how long?

There is little driftwood on Driftwood Beach except for the occasional stick. Rather, the “driftwood” consists of dead trees, mostly live oaks (Quercus virginiana) that are no longer on high ground. They have not drifted from anywhere. They remain in situ (Figure 3, personal photographs). The live oak skeleton in the left panel is now in the ocean along with many others. The dead trees in the right panel (live oak and palm) are at the edge of the rising highwater mark, where they have been killed by seawater.

There is naturally some discussion about whether Driftwood Beach is the result of normal changes in the shoreline due to the ever-present wind and large tidal flows. But similar areas are now more common than before on other Sea Islands. Whatever the cause, which is not necessarily unitary, this severe erosion on Jekyll Island has led to interventions that will be futile. Rising seas cannot be stopped. But several hundred yards south of Driftwood Beach, “Johnson Rocks” [6] have been piled at least 15-feet high, separating the remnant of a broad expanse of beach from the condominiums and houses behind them (Figure 4). This continues for more than two miles to the south and will eventually continue farther, provided the State of Georgia is willing to spend the money (Jekyll Island is essentially a state park, purchased for $675,000 in 1947 from the remnants of the Jekyll Island Club in what was termed Thompson’s Folly in honor

of then Governor Melvin E. Thompson). The sand behind the rocks has been imported.

The extensive walkways over the Johnson Rocks are expensive but temporary, especially on the ocean side. During my visit in May 2024 the distance from the last step to the sand was a 4-foot drop at several sites, which is too far for those of a certain age to reach the beach. The story of King Canute demonstrating his fundamental powerlessness to his courtiers comes to mind.

Suggestions of how to get the message across are most welcome. AGW is not “just the weather,” but when “the ‘market’ is the measure of all things,” nothing else matters. A good friend from our days as baseball teammates responded to my topophilia-driven angst by telling me that planet Earth is too large for humans to damage it, so this is just the way things are. Actually, no. The ozone hole is under repair intentionally, to use a keyword. Fifty years ago, the Clean Water Act returned speckled trout (a species unable to tolerate industrial pollution) to the local tidal river less than a half mile from my childhood neighborhood, while the Clean Air Act put Spanish moss back on the branches of the live oaks as local air pollution diminished in the 1970s.

Perhaps these successes were small things. According to David Wallace-Wells, we are too far gone to do anything but manage, probably poorly, the coming catastrophe. I suspect he is correct. But Michael Mann claims that all is not necessarily lost. Rebecca Solnit and colleagues tell us that it is Not Too Late, as they would. In idle moments I would like to ask Hank Paulson what he thinks. Several years ago, he and his wife Wendy bought Little St. Simons Island so that it could be preserved in perpetuity, through an easement granted to the Nature Conservancy, as the little paradise it is (though expensive to visit, but not to beach a boat on the shore of Buttermilk Sound and walk around for a few minutes while ignoring the implicit “No Trespassing” signs). The island’s “perpetuity” might not outlive his grandchildren.

Finally, the little book Sea Islands of Georgia: Their Geological History (Endnote 3) that has taught me much about The Most Delightful Country of the Universe concludes with this:

The islands are being constantly modified. There is no loss but a gain of growth from this modification. The sea level is rising faster than their growth. If no change occurs in the present rise of sea level they will be submerged in one thousand years. There will be another and quite similar chain born as these pass out.

A change has occurred and there can be no denial that this change of a few hundred years at most is our doing. This is obvious to the most casual observer who is willing to look. As Abraham Joshua Heschel said in a different but apposite context, “Few are guilty, but all are responsible.” The willfulness of politicians and corruption of science, by scientists and their antagonists-with-agendas, are not helpful. Nevertheless, hope is the basis for action while optimism is a foundation for nothing but lassitude and ultimately despair. There is work still to be done, and it will have to be done by citizens rather than consumers. Perhaps it is not too late, after all.

Notes

[1] McKibben’s outright dismissal of the question of funding for 350.org when asked in Michael Moore’s Planet of the Humans was not his finest moment, despite what one thinks of this “imperfect” documentary.

[2] Sidney Lanier (1842-1881): The Marshes of Glynn. Text is here. A not unreasonable gloss is here. Sidney Lanier is not for everyone, especially Robert Penn Warren and his fellow Southern Agrarians and New Critics. But Jay B. Hubbell ranked Sidney Lanier with Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman among late-19th century American poets…but for tuberculosis. The history of the Sea Islands and adjacent grounds after the Colony of Georgia succumbed to the political economy of its near neighbor to the north, despite significant resistance, is another matter altogether.

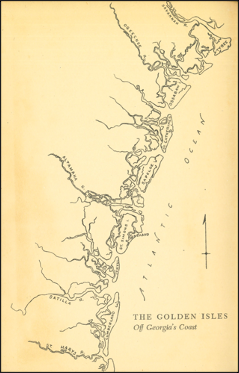

[3] The Sea Islands of Georgia: Their Geologic History. Count D. Gibson, University of Georgia Press, 1948. Only Jekyll, St. Simons/Sea Island, and Tybee are connected to the mainland by causeway.

Thus, the other islands have remained mostly in their natural state. Because I love maps, I cannot resist adding the map from the endpapers of the book here. Little St. Simons is the large island, mostly marsh, to the north of St. Simons/Sea Island. Wassaw, the small island between Ossabaw and Tybee, is not labeled.

[4] The Current is one of the excellent new independent news sources that have become essential as the traditional newspaper business has collapsed in on itself due to the rise of the internet.

[5] Existential(ism) for me means Camus, Sartre, and Kierkegaard. Who doesn’t feel like Sisyphus these days, or have a sense of sickness unto death or being nothing? Our collective political nervous breakdown has hijacked this previously useful philosophical concept, and “existential” has become just another PMC/neoliberal keyword such as freemarket, democracy, proactive, intentional, holistic, artisanal, mindfulness, and wellness. Still, it fits here.

[6] The seawalls of granite boulders common in the Sea Islands were first installed after Hurricane Dora (1964) washed away several beachfront houses on St. Simons Island, just to the north of Jekyll Island. The were promised by President Johnson during a tour of damaged areas after the storm. The seawalls are intended to protect the shore from the action of the Atlantic Ocean. It is not clear they do so in the long term. Previously the kinetic energy of waves and high seas dissipated harmlessly in the sand dunes above the high-water mark. While such seawalls work in the short term, it has been argued that Johnson Rocks also direct forces downward and contribute to beach erosion where they are installed. This is evident in the Village of St. Simons near the lighthouse, in sight of Driftwood Beach to the south across St. Simons Sound. The Johnson Rocks have done their job of protecting the village except during Hurricane Irma (2017) which was accompanied by an extremely damaging tidal surge from the northeast – something of a wakeup call for the complacent, but real estate prices have only continued to skyrocket. Where there was beach even at high tide not so long ago the water is now 6-8 feet deep. Previously no one built close to the shore or in the dunes between high ground and the ocean, but zoning commissions everywhere are amenable if the price is right. The only thing likely to alter that is a final collapse of the property and casualty insurance business.