Yves here. Wolf Richter provides some important sightings confirming that there’s plenty of liquidity in the financial system, which is at odds with what the Fed has been trying to achieve with its rapid interest rate increases and its intention not to back off until it sees results. We said from the get-go that the Fed was unlikely to be able to whip inflation via interest rates increases, short of killing the economy stone cold dead, since many of forces driving this inflation were the result of supply factors that interest rates cannot address.

But Wolf’s factoids suggest that the Fed tightening is failing even in its own terms, of trying to dry up credit to dampen down business activity and above all, wages. Why might that be?

Looking at money supply is a poor metric. Monetarist experiments in the US and UK in the early 1980s established that changing money supply levels correlated with no significant macroeconomic variable, even on a lagged basis. A big reason, if you believe in that framework, is that prices are supposedly a function of monetary velocity as well as supply. What might be increasing monetary velocity? Various forms of shadow banking, ranging from the rise of private credit funds, as opposed to banks, as suppliers of funds. Another is the use of derivatives to increase leverage, witness the Fed-approved bank use of synthetic risk transfers, which allow banks to blunt the effect of tighter capital requirements.

In the runup to the 2008 crisis, some analysts and reporters (including yours truly) took note of and tried to understand the so-called “wall of liquidity” which resulted in pervasive underpricing of credit risk. That’s finance-speak were “lenders not demanding high enough interest rates to compensate for the risks they were taking.” The culprit then was structures and strategies that created leverage on leverage, particularly asset-backed CDOs and credit default swaps. One leverage on leverage strategy operating now is private equity subscription credit lines, where private equity firms borrow against unused limited partner capital commitments rather than simply use that source of funding. But it is well nigh impossible to get good data on the use and impact of this approach.

Readers who have intel on subscription credit lines and other leverage on leverage strategies are very much encouraged to speak up in comments.

By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

One of the big surprises this year is that the Fed’s 5.5% policy rates and $1.1 trillion in QT have neither meaningfully tightened financial conditions nor slowed the economy.

The Fed has been “tightening” since early 2022 in order to “tighten” the financial conditions, and these tighter financial conditions are then supposed to make it harder and more expensive to borrow which is supposed to slow economic growth and remove the fuel that drives inflation. “Financial conditions,” which are tracked by various indices, got a little less loose, and then they re-loosened all over again. It’s almost funny.

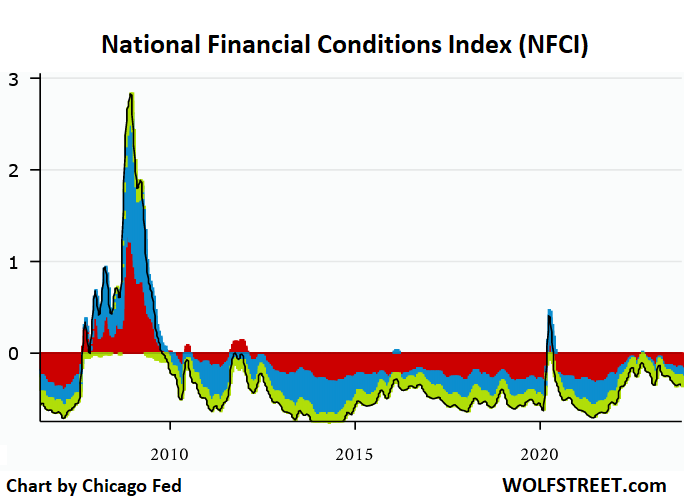

The Chicago Fed’s National Financial Conditions Index (NFCI) loosened further, dipping to -0.36 in the latest reporting week, the loosest since May 2022, when the Fed just started its tightening cycle. The index is constructed to have an average value of zero going back to 1971. Negative values show that financial conditions are looser than average, and they have been loosening since April 2023, after a brief tightening episode during the bank panic (chart via Chicago Fed):

You can see in the chart above how financial conditions tightened in March 2020, but not for long – by May 2020, as the Fed was dousing the land with trillions in QE, they were already loose again.

So, despite the rate hikes and QT by the Fed, financial conditions are as loose as they were when the Fed had just started tightening in May 2022, and they are far looser than the long-term average, though they have become somewhat less loosey-goosey than during the free-money era starting in mid-2020 through early 2022.

The long-term chart below of the NFCI shows what happens when financial conditions tighten so much that they strangle the economy, as they did during the Financial Crisis. The March-2020 spike barely registers in comparison.

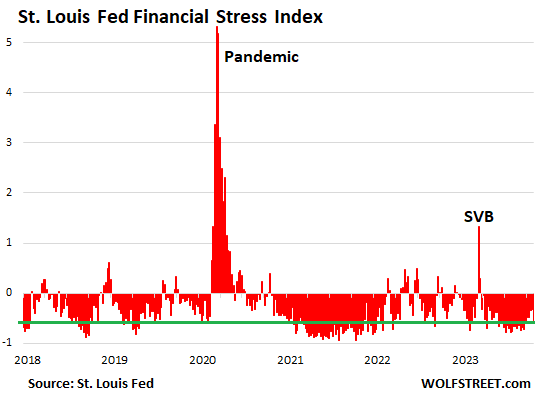

The St. Louis Fed’s Financial Stress Index takes a similar approach and measures financial stress in the credit markets. The zero line denotes average financial stress. Negative values denote less than average financial stress. In the current week, it dropped to -0.56. The green line shows this current value across time and denotes that credit markets are still in la-la-land.

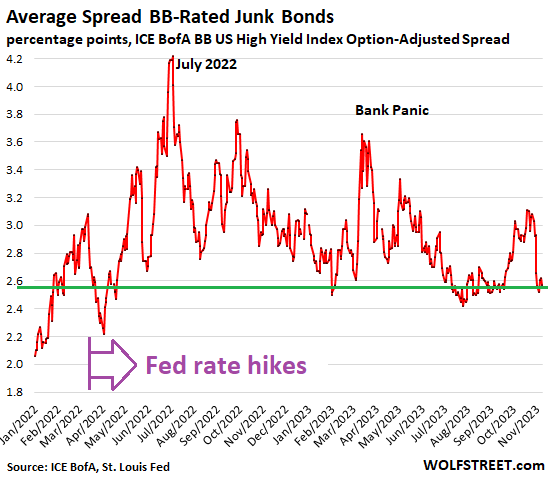

The BB-rated junk-bond spreads are another measure of financial conditions. Corporate bond yields should rise or fall with Treasury yields. But a wider spread between those corporate bond yields and Treasury yields indicates tighter financial conditions; a narrower spread indicates looser financial conditions.

The average spread of BB-rated bonds, the less risky end of high-yield (my cheat sheet for corporate bond rating scales) narrowed further yesterday to 2.57 percentage points. So this is going in the wrong direction, in terms of what the Fed wants to accomplish.

Sure, some sectors are stressed and financial conditions tightened in those sectors, such as the office sector of commercial real estate, but the troubles in the office sector have structural causes, including working from home and the corporate realization that they don’t need all this vacant office space that they have been hogging for years, and will never grow into.

And home sales have plunged because potential sellers don’t want to give up the 40% to 60% price spike they got over the period of pandemic QE; and buyers just laugh at those prices and go blow their down-payment on all kinds of stuff and services, including travels and cars – new vehicle sales surged 20% year-over-year in Q3 – contributing to consumer spending.

And sure, the major stock indices are down from their highs a couple of years ago. Sharply higher yields (lower bond prices) have put pressure on bank balance sheets, and a few, run by goofballs that failed to manage this properly, have collapsed.

But consumers are working in record numbers and are making record amounts of money, after receiving the biggest pay increases in 40 years that in 2023 are finally outrunning inflation, and they’re spending huge amounts of money and are still able to save some. We’ve been lovingly and facetiously calling them our Drunken Sailors here since at least March.

And companies, flush with cash from selling a tsunami of bonds at low rates during the Fed’s 0% era, are investing, including in a huge construction boom of factories. And they’ve raised their prices, because, you know, this is inflation, and they got away with it.

And the true Drunken Sailors, the folks in Congress, are throwing trillions of dollars a year in still easily borrowed money at the economy to fuel growth and inflation.

So the Fed’s policy rates that went from 0.25% to 5.5%, and its $1.1 trillion in QT so far have failed to broadly tighten financial conditions and slow down this train.

Could it be... that so much central bank liquidity was created during and before the pandemic that financial conditions cannot meaningfully tighten, despite the Fed’s tightening, until this liquidity gets burned up?

The Fed alone, not counting other central banks, created $4.8 trillion within two years of giga-money-printing, as Musk would say; it has now removed $1.1 trillion of it via QT.

Could it be, with so much liquidity still out there, that it might take a lot more and a lot longer to tighten financial conditions enough to where they have even a chance of removing the fuel from inflation?

And that’s kind of funny because if financial conditions don’t tighten enough to slow the economy and remove inflationary fuel, and if it then turns out that this dip in year-over-year inflation rates was just a “head fake,” to then resurge again, as Powell said he suspects it might, the Fed will go at it with more rate hikes. Powell made that clear. With credit markets still blowing off the Fed, are they trying to make sure that “higher for longer” gets entrenched? That would be funny.