The European Union on October 4 took a big step in its budding trade war with China. Member states voted to enact new tariffs on China-made battery electric vehicles of up to 35.3 percent. They will be imposed on top of the 10 percent duty already imposed on car imports and is to remain in place for five years. Beijing is already responding by imposing its own tariffs on European brandy and is also conducting investigations into imports from the EU of dairy products, pork, and large-engine cars.

European officials are expressing shock that Beijing is retaliating.

“I find these measures incomprehensible. There is no justification for them,” said Sophie Primas, Junior Trade Minister of France, which will be hit hardest by Beijing’s move on brandy.

What Is De-Risking? Who Is Pursuing It and Why?

In a moment of truth the EU’s top diplomat Josep Borrell recently admitted that “Europe must not oppose itself to China’s rise, because this rise is a fact. China … is at the cutting edge of all technology.”

And yet Europe goes down the path of “de-risking” from China nonetheless.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen who coincidentally pioneered the term “de-risking” is largely running the show. While she was by all accounts a complete failure as German defense minister (2013-19), she has found her niche as Commission president, successfully organizing the EU’s executive arm so that she wields almost complete authority in ways that previous rulers attempting to bring all of Europe under their control could only dream of. Her reign in likely aided by the fact she has no problem bending the knee to Washington. No doubt, the US is looking forward to more of what Ursula says will be a tough “foreign economic policy” in her second “mandate.”

EU member states added new instruments to Ursula’s toolbox during her first five-year term, such as the Foreign Subsidies Regulation, International Procurement Instrument, an Anti-Coercion Instrument, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, and the EU Critical Raw Materials Act. Taken together, they mean Queen Ursula can slow trade with China to a trickle if she or her partners in Washington see fit.

Her “de-risking” playbook has three stated goals: to protect the EU economy from outside encroachments, to promote its competitiveness, and to partner with “friends” to mitigate its vulnerabilities. In practice, however, it equates to economic confrontation with Russia and China while encouraging a wholesale takeover of Europe by the US.

Prior to her humiliating 2023 trip to Beijing, von der Leyen elaborated on her “de-risking” strategy in a speech on EU-China relations at the Mercator Institute for China Studies and the European Policy Centre. Here’s a key excerpt:

The starting point for this is having a clear-eyed picture on what the risks are. That means recognising how China’s economic and security ambitions have shifted. But it also means taking a critical look at our own resilience and dependencies, in particular within our industrial and defence base. This can only be based on stress-testing our relationship to see where the greatest threats lie concerning our resilience, long-term prosperity and security. This will allow us to develop our economic de-risking strategy across four pillars. The first one is: making our own economy and industry more competitive and resilient.

The second pillar is using her new tools, the third is more “defensive” tools (Ursula loves tools), and the last is alignment with partners, and we all know who that is.

There is a belief in Brussels that Ursula and company largely constructed pillar one and two during her first five-year term, and now it’s time for three and four, but it’s hard to square that with reality.

While Washington and Brussels’ agendas unsurprisingly overlap, the EU continues to be much more exposed to China than the US for both exports and imports, with the latter increasingly “strategic.” Gone are the days of China’s imports consisting of textiles, shoes, and furniture. They are now pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and critical raw materials.

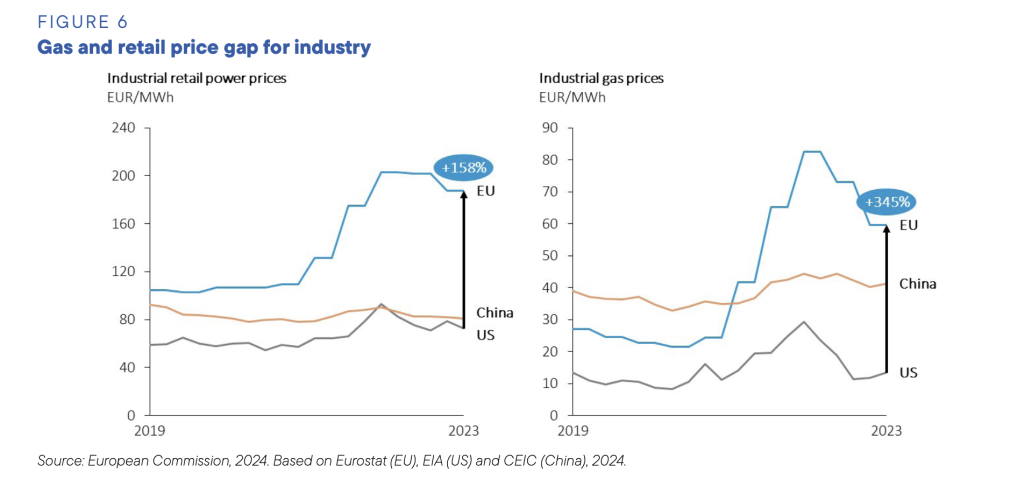

Von der Leyen likes to tout her tools like the bloc’s Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA), which aims for the EU to process 40 percent of the strategic raw materials it uses by 2030. The NZIA allows projects to bypass many environmental and social impact reviews, but there’s no budget, and the policies do nothing to change Europe’s disadvantages, which include a lack of subsidies compared to the US and China and much higher energy costs thanks to their “de-risking” away from Russian energy. One might think that disaster would serve as a warning, but Ursula and company are plowing ahead with “stress-testing our relationship to see where the greatest threats lie concerning our resilience, long-term prosperity and security” despite not having the EU “economy and industry more competitive and resilient.”

About that stress-testing. It’s strange that the trans-Atlantic relationship is never put to the same test as with Moscow and Beijing. Second, is this some new form of international relations that Ursula is pioneering? Intentionally damaging ties with world powers in the name of stress-testing? That line of strategic thinking seems to be widespread in Brussels.

The German Chairman of the International Trade Committee (INTA) at the European Parliament sums it up when he argues that “sometimes you have to put a gun on the table, even when you know that you might not use it.” Even if we discount Chekov’s gun principle, are there not other downsides to that strategy, such as the other side thinking you might use the gun and shooting you?

Is this a wise course of action when the EU relies on China for more than 90 percent of its supply of certain drugs, chemicals and materials — and in some cases there are no substitutes?

Similar to the whole Russia fiasco, it won’t be people like Lange and Ursula taking the bullet, but the working class across Europe. Somehow that never gets factored into these bright ideas like stress-testing.

Is De-Risking Proving Effective?

Two charts from an August report from the Peterson Institute for International Economics show how the EU is more reliant than ever on China.

A few observations of the above charts courtesy of the Conversable Economist:

In short, these patterns seem to suggest that imports not coming from China to the US economy are, in a substantial way, ending up in the EU economy instead. This pattern suggest that if the goal of US trade policy is to reduce China’s footprint in the global economy, it is unlikely to do so. Indeed, given that imports often pass through the production process in several countries on their way to a final product, it’s plausible that some Chinese exports are going to Mexico and the EU, being incorporated into other products, and then ending up as US imports.

Both of those observations would suggest the near impossibility of “de-risking” from China. It currently produces 90 percent of the active material for EV battery cathodes and 97 percent of the active material needed for anodes. It also assembles 66 percent of the world’s EV battery cells. This means China has unrivaled leverage over the entire automotive supply chain. That’s why the German auto sector was so opposed to the EU kicking off a trade war with China. As Adam Tooze explains the charge that the German auto industry erred by becoming “dependent” upon the Chinese market is completely wrong headed:

If you are in the business of making cars and selling cars at the global level, which is the aspiration of a VW and the German high-end marques, but also the likes of Toyota and, perhaps, GM, then being in China is not a basket you do or don’t put your eggs into. China is not a market that you can derisk from, or balance with other markets. It is the market, it is the country where both in terms of trends of consumption and production, the future of the global industry is likely to be decided.

EU businesses’ unwillingness to voluntarily de-risk is why we see Ursula and company stepping in to force the EU to wall itself from China.

***

Another part of the EU’s efforts at de-risking and competitiveness involve the struggle to produce chips in the bloc.

The world’s largest chipmaker, Taiwan’s TSMC, is working on an $11 billion project in Dresden, a venture that’s touted as a major step towards the EU’s goal of having more microchips made in Europe. Germany’s car industry could benefit from the chips rolling off a domestic production line, but the EU had to pick up about half of the tab in order to get the project off the ground, and there are doubts about its long-term viability.

An Intel plant in Magdeburg, Germany, was supposed to be Europe’s only facility making the most advanced computer chips and be operational by the end of the decade, but Intel postponed the $30 billion investment ($10 billion of which was to come from German state aid) to reduce its spending amid the company’s financial woes, and there are reports that it’s a coin flip whether Intel abandons the project entirely.

There is an effort to blame labor unions and high wages for the problem but it chiefly comes down to two issues. The first is high energy costs. Due to the EU’s decision to cut itself off from Russian pipeline gas, it faces uncompetitive energy costs.

Enormous amounts of electricity are needed for the supercomputers or chip-making factories to function properly. In addition to the EU’s high costs, there are loads of uncertainty about energy supply in the future, which is a no-no for business investment.

There are also problems finding enough workers. After decades of elites shipping industry to China, it’s not easy to flip a switch and make the necessary skilled labor appear.

All that offshoring is coming back to bite Western capital now. Beijing is hardly to blame for taking what was being offered, but now that it’s ready to turn around and sell advanced clean tech solutions, the West says no thanks, we want to be in control of the Green future. Problem is, that’s easier said than done.

De-Risking Downsides

There are many.

If you’re concerned about democracy, there is a major downside to the de-risk mania. As evidenced above, European countries continue to cede even more sovereignty by giving Ursula and the Commission various new tools to conduct the de-risking efforts.

If you’re concerned about Germany, a trade war with China adds to the endless bad economic news from the country. A day after the country marked 34 years of unification, the tariff vote might go down as another milestone. The country’s auto industry, which has driven Germany’s economic rise since its post-WWII economic miracle, is in big trouble, and a trade war with its biggest market (where German cars were already on the decline) won’t help. While the German political class offers some rhetorical dissent to the de-risking strategy (Chancellor Olaf Scholz made a show of his opposition once it was clear the measure was going to pass), they have fallen in line despite the complaints from the auto industry. Meanwhile, Belin sends warships through the Taiwan Strait. Why? It must prove its bona fides as US, British, French, Dutch and Canadian warships all recently made the journey.

The country is nearing a breaking point as insurgent political parties on both the left and right that favor less Atlanticism and repairing ties with Russia and China continue to gain ground, and Berlin considers undemocratic responses to keep them at bay.

If you’re concerned about climate change, the de-risking strategy is a setback for the deployment of more “clean” technology. A decarbonized economy sounds great, but even the most optimistic timelines admit that possibility is years away and requires massive amounts of investment. It gets harder to pay for as economies are struggling, government budgets are broken because of energy costs, and you’ve walled yourself off from the country producing most of the green products.

More local production is a worthwhile goal, but there’s the not-so-minor inconvenience that China increasingly dominates most stages of the global green technology industry. Here’s Adam Tooze discussing Brian Deese’s call for a Clean Energy Marshall Plan in Foreign Affairs:

As Deese gamely observers: “The good news is that most of the technologies necessary, from solar power to battery storage to wind turbines, are already commercially scalable.” Yup! this is true. But the problem from Washington’s point of view is that it is not the US that is leading that commercialization. But China. On a huge scale. Against US resistance.

The EU will no doubt hurt China with a trade war as China is reliant on the EU to absorb its excess capacity in clean technologies, but it will be cutting off its nose to spite its face.

And this is really the crux of the issue. The EU is not prepared to “de-risk.” It is not possible to simultaneously embrace neoliberalism while pursuing an industrial policy. The result — intentional or not — will be evermore vassalage to the US, which might be in a better position than the EU but faces its own neoliberal-industrial conundrum.

The EU’s de-risking plan with China appears even more ill-fated than the one with Russia. That’s because while other gas supplies are available — albeit less reliable and more expensive — that will be less so with critical materials, which China dominates.

According to SWP, Germany’s extremely ambitious goals in the area of the green energy and mobility transition alone can hardly be achieved without economic exchange with China. Here we can see why:

Who Benefits?

Several of the myriad crises that Europe finds itself in today (energy, deindustrialization, vassalage to the US due to confrontational policy towards Russia, and going down a similar path with China) can be traced to the desire of the bloc’s elites along with those in the US to control the green tech of the future. Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic recently stated the obvious when explaining the reason for the European elite’s belligerent policy towards Russia is because it has all the resources that Europe wants control over.

Like that failed strategy, which produced many beneficiaries — few of which were in Europe — so too will the strategy to “de-risk” from China.

Hungary, which continues to receive Russian gas (and has the lowest electricity costs in Europe) might be able to capitalize. (There’s a reason Brussels detests Orban so much).

Hungary currently receives nearly half of China’s foreign direct investment into the bloc. China’s battery giant, CATL, is making its biggest-ever overseas investment of approximately $9.7 billion in the country, and EVE Energy, another Chinese battery manufacturer, is making a $1.32 billion investment to produce large cylinder batteries.

Türkiye, which is in the EU customs union, is getting a $1 billion production facility from electric car giant BYD and is in advanced discussions with Cherry Automobile for another.

But we’ll have to wait and see. The EU is considering attempts to wall off backdoors into the bloc market, as well. In the eyes of Brussels, these unwelcome “concessions” in places like Hungary are a security threat since China is a geopolitical rival of the EU. In response, the EU is considering strengthening its Investment Screening Mechanism, which would give Ursula and the Commission the power to prevent such deals.

The biggest beneficiary to the EU’s de-risking efforts, however, is likely to be the US.

Western battery makers and other clean tech companies are increasingly moving to the US due to lower energy costs and subsidies. China de-risking could be another boost for US LNG. That’s because what the EU is doing by going down the derisking path is effectively saying that it does not want Chinese clean technology. Couple that with the resistance to Russian energy and it means an extended reliance on LNG.

Perhaps ironically, among the biggest proponents of the China de-risking strategy are the German Greens. I say perhaps because their policies — intentional or not — frequently lead to decidedly un-green energy outcomes just as they did when Germany cut off Russian pipeline gas, closed its remaining nuclear power plants, and started burning more coal to make up for the energy shortfall.

Should critical materials increasingly get caught in a trade war between Europe and China, there will be middlemen — like those selling Russian oil to Europe at a markup — eager to step in and profit while Europeans face high prices and less competitiveness.

Competitiveness. That word is thrown around a lot in Brussels these days, and we’re getting a clearer look at what the remedies are going to be. That’s where the US is really set to benefit.

The argument of Queen Ursula, Mario Draghi and company is that Europe needs more concentration, more “productivity” and more privatization in order to build technological supremacy. In other words, it needs to double down on neoliberalism and become more like the US — increasingly by selling off assets to US firms. That will have to be a story for a future post, but for now it’s enough to say, that’s a shame.

Even after decades of neoliberal reforms, Europe might still lag in competitiveness as measured by capital interests but those computations of course don’t take into account its still-superior quality of life — from better population-wide healthcare and work-life balance to more unions and less economic inequality.

All these upsides for labor are of course downsides for capital. If the first Cold War was a time when Europe built its welfare states, the second appears poised to finally bring them crashing down.