This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 212 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year,, and our current goal, strengthening our IT infrastructure.

The grim message, that the recent debt crisis in Sri Lanka is likely a harbinger of debt crises in other overburdened lower and middle income countries, comes in an important paper that we have embedded at the end of this post, Chronicles of Debt Crises Foretold, by Anis Chowdhury and Jomo Kwame Sundaram. Regular readers will recognize their names, since we have cross posted many of their articles from Jomo Kwame Sundaram’s website. Both are well-recognized development economists who among other things held important positions at the UN. This paper codifies arguments and evidence they have presented across recent posts and articles.

The paper is very carefully argued and information rich while being accessible. I encourage you to take the time to read it in full, particularly if you are in finance, economics, or otherwise interested in . But it paints a very troubling picture of how neoliberal practices, particularly encouraging developing economies to seek funding even more than ever from fragmented private lenders while pressing them to pursue sub-optimal economic policies, has put them in an even more fragile position than they were during the early 1970s-1980s debt crises.

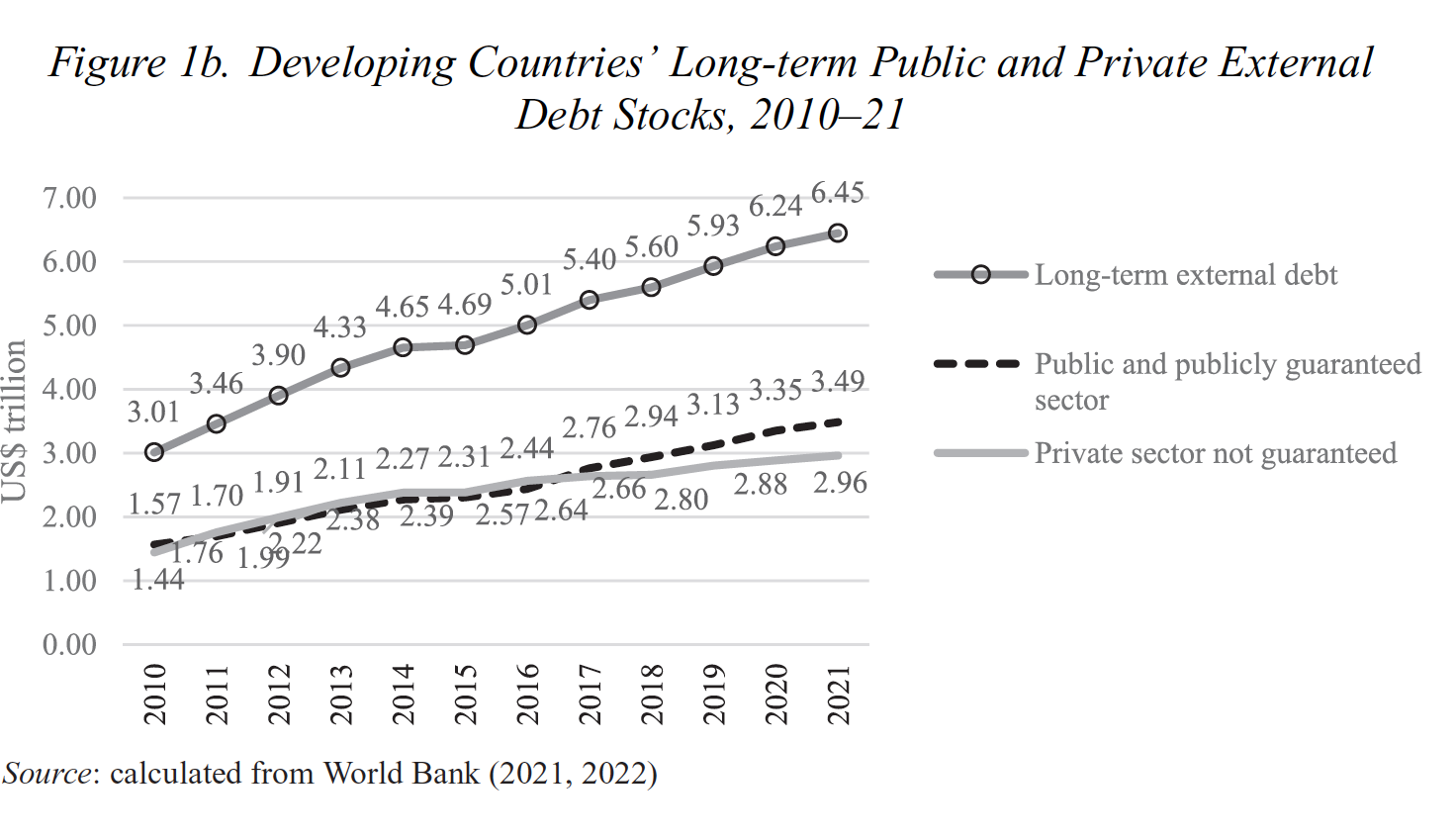

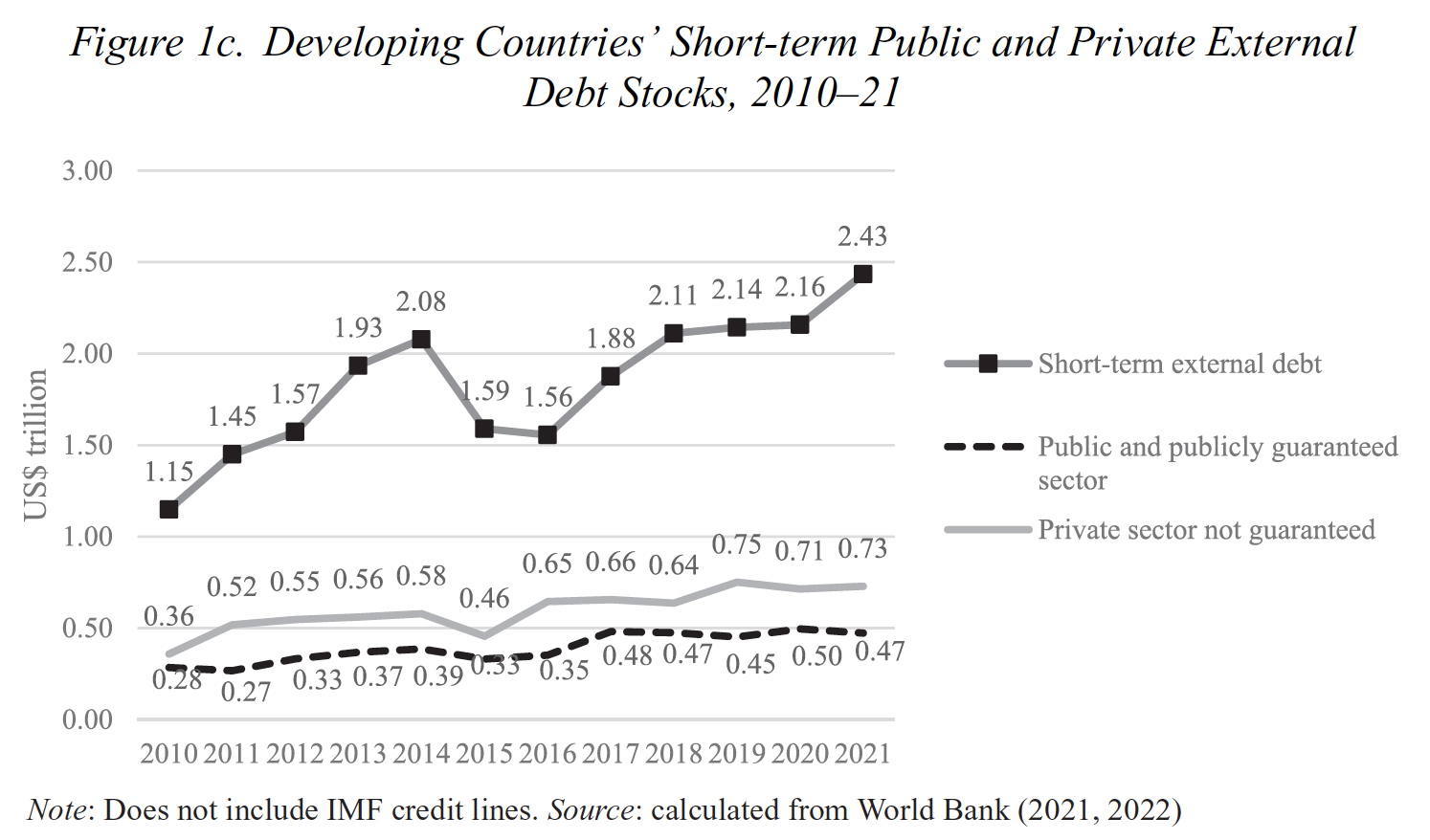

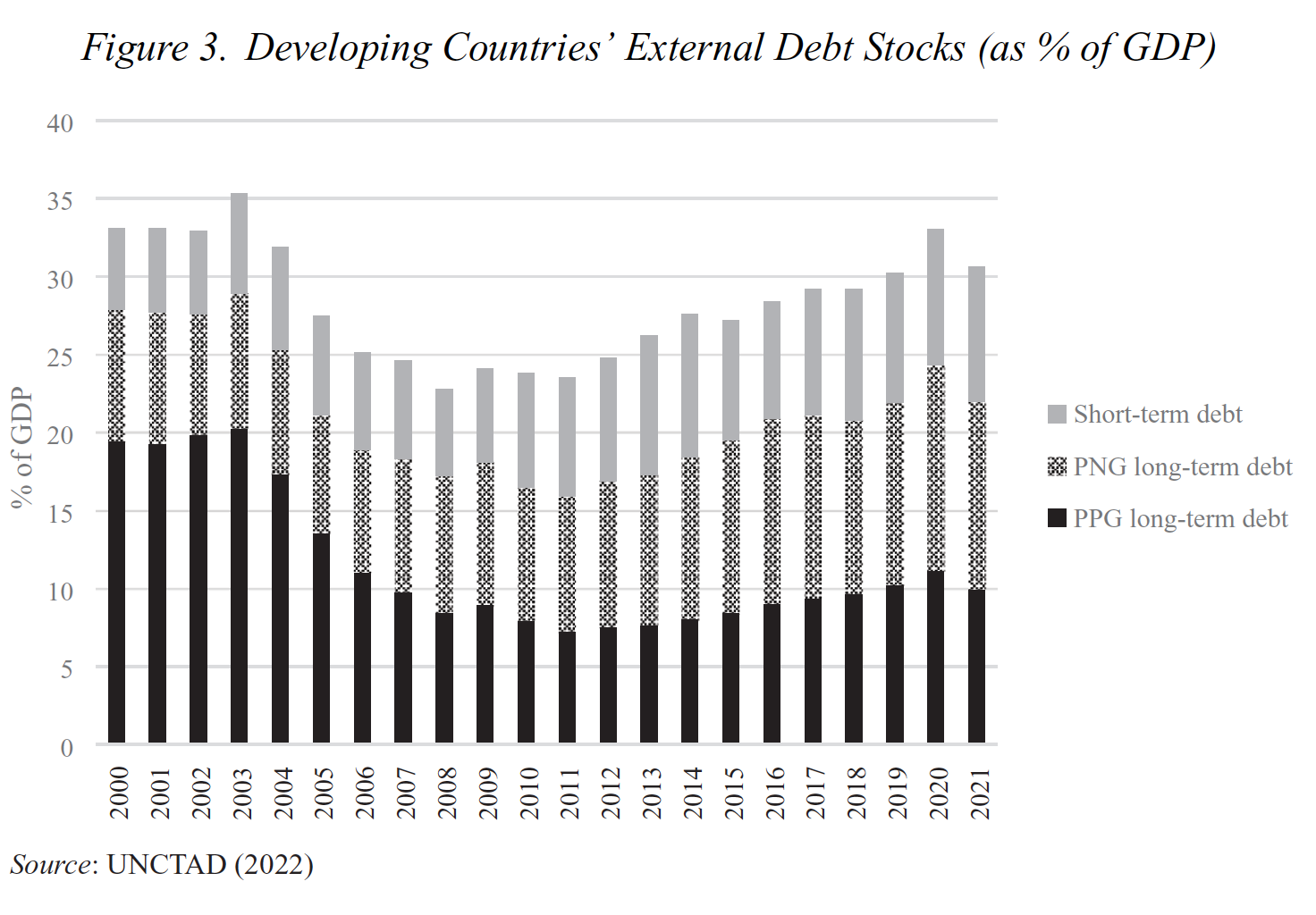

At the risk of oversimplifying, the article presents three sets of interlinked observations. The first is how a large cohort of lower and middle income countries have come to have even higher debt burdens than the afflicted countries did before the so-called Latin American debt crisis. The very short version is the countries at risk had high debt levels going into the Covid crisis and then borrowed more. While the interest rates on that debt was low at the time, interest rates have since gone up considerably due to tightening by the Fed and other advanced economies, forcing emerging economies to fall in line or risk a currency rout. So they are at risk of facing punitive rates or being unable to refinance at all when current debt matures. Note in particular the high level of short-term debt in the charts below:

The picture does not look as bad as a whole in GDP terms until you focus on the fact that the proportion of both short-term debt (subject to rollover risk and interest rate increases) and private debt has risen over time. Both are much harder to restructure>

The second is the way that emerging economies generally get the short end of the stick from Mr. Market and international organizations. For instance, the authors point out that rating agencies operate in the reverse manner to the way they handle advanced economy sovereign debt (which sets the base level for private borrowing): they are fast to downgrade and very slow to revise ratings upwards. Similarly, as we saw with the Greece bailout crisis, the IMF is usually the key actor in any proposed “Paris Club” country debt restructuring. But accepting IMF programs, as in austerity, is a condition for any debt restructuring. Many borrowers have worked out that these requirements are economically counterproductive and thus often don’t take up theoretically available assistance.

As part of this theme, the authors also describe how the policies advanced economies have foisted on developing economies, such as floating exchange rates, open trade and financial markets and emphasizing exports of primary commodities and raw materials. Another source of vulnerability is that developing economies rely heavily on corporate taxes for government revenues, when multinationals play transfer pricing games to avoid showing much revenue there. Chowdhury and Sundaram deem tax reforms (scheme to counter so-called “base erosion and profit shifting”) to be eyewash (they say that in economese). It also included a detailed discussion of the failure of advanced economies to deliver on aid promises and lame excuses for stingy debt relief.

The third thread is that the current structure of lending makes the bad vulnerable borrower situation worse. There are more lenders across more countries, and a far larger proportion are private borrowers who will try to extract blood from poor counties and companies in distress. The authors point out that the dominant role of the US and the exposure of US banks (notably Citi) in the Latin American debt crisis meant the US was at risk of a banking crisis, and thus was motivated to facilitate debt restructuring. And even that one did not proceed quickly. From the article:

Although only a few banks, mainly from the US and UK, were involved in the 1980s’ debt crises, it took nearly a decade to arrive at some debt workout mechanism. Now, with so many diverse commercial lenders, quick resolutions of future debt crises are likely to prove almost impossible….

Mechanisms for fair and orderly sovereign debt restructuring involving commercial lenders are still lacking, despite repeated appeals, especially since the 1980s’ debt crises. Following the 1997–98 Asian financial crises, IMF proposals included standstill provisions comparable to elements of legally prescribed US bankruptcy proceedings (Cui, 1996). When a creditor cannot repay in full, temporary cessation of all payments is followed by an orderly process that works out how much creditors can collectively expect to receive, instead of a disorderly, and ultimately costly, rush to exit. This idea was incorporated into the proposed IMF Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism, ‘but did not attract sufficient support from major countries and has not gone forward’ (Stevens, 2007), due to opposition from large commercial lenders, mainly from the US.

The lack of a fair and orderly debt restructuring mechanism has added insult to injury. Commercial lenders charge much more, ostensibly to cover higher default risks, but when default happens, they refuse to refinance, restructure or provide relief. Instead, some act opportunistically, for example, holding countries hostage, regardless of consequence, as ‘vulture capitalists’. When countries seek emergency credit from the IMF, it often imposes ‘one-size-fits-all’ austerity measures. In many cases, these impair growth prospects and undermine social stability. It is therefore unsurprising that many countries are reluctant to seek IMF ‘help’, as a temporary liquidity crisis can deteriorate into a solvency or debt sustainability crisis.

The paper, both at points throughout but particularly at the end in a section called “Popular Western Media Narratives” addresses the propensity to blame recent Chinese lending, particularly as port of its Belt and Road Initiative, for emerging economy debt stresses. Even if the recent Chinese loans could be depicted as the straw that broke the camel’s back, the Chinese on the whole provided more debt relief than advanced economies. From the article:

In terms of China’s involvement as an increasingly important creditor, the World Bank (2022) estimates that LMICs’[low and middle income countries’] combined debt to China was US$ 170 billion at the end of 2020 — more than three times its 2011 level….LMICs’ Chinese debt constituted less than 20 per cent of total borrowings in most cases, and less than 15 per cent for all LICs …

Western observers, including the IMF and World Bank, accuse Chinese lenders of lacking transparency (Bretton Woods Committee, 2022). However, independent studies have debunked the China ‘debt trap’ narrative. For example, a Chatham House report (Jones and Hameiri, 2020) found that Sri Lanka’s undeniable debt distress was mainly due to excessive borrowing from Western-dominated capital markets — not Chinese banks…

A Lowy Institute study (Rajah et al., 2019) came to similar conclusions regarding China’s lending to South Pacific island states: ‘Our analysis, however, finds a nuanced picture. The evidence to date suggests China has not been engaged in deliberate “debt trap” diplomacy in the Pacific’ (ibid.: 1). China announced that it was ‘forgiving’ 23 interest-free loans to 17 African countries (Monteiro and Hancock, 2022)….

It has been estimated that 26 per cent of total debt-service payments by 68 DSSI countries in 2022 went to China, compared to 17 per cent to bondholders and 9 per cent to the World Bank-IDA (Yue and Nedopil, 2022). By the end of 2020, China had deferred payments of US$ 2.1 billion to address DSSI countries’ debt, compared to US$ 2.5 billion deferred by Paris Club members. China promised to redistribute US$ 10 billion of its US$ 38.2 billion worth (26 per cent) of newly issued IMF SDRs to African countries.

By comparison, other G20 countries — such as France, Italy, the US and the UK — committed about 20 per cent of their SDRs for redistribution to emerging market economies (ibid.). Of the LICs that sought DSSI

relief, China contributed to 63 per cent of debt-service suspensions, despite holding only 30 per cent of debt claims, with 23 countries (including 16 in Africa) benefiting from China’s G20 DSSI relief (Brautigam and Huang, 2023).China has also been criticized for insisting on the participation of the IMF, World Bank and other MDBs in debt relief; allegedly, it has done so to evade demands by the US and IMF for China to provide more debt relief (Lynch, 2023). However, China’s insistence on MDB participation is not only not new, but is also supported by others (Kebret and Ryder, 2023), including many African countries.

The paper also features the recent Sri Lanka debt crisis as a case study.

There are grounds for worry. Climate change, slower growth in China and weakening demand from Europe, and efforts by the US to “reshore” (which is happening, albeit not to the degree advertised) all have the potential to whack exposed nations. And a further wild card is BRICS expansion. The article points out in a footnote:

The top 10 borrowers, defined as those with the largest end-2020 external debt stock, were Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, the Russian Federation, South Africa, Thailand and Turkey

I see the Collective West as quite capable of explicitly withholding debt relief if BRICS+ gpt too far too fast with its ‘reduce the use of the dollar” project.1

_____

1 Your truly remains of the view that this will take much longer than commonly believed. Two of many examples: Southeast Asian countries already do a fair bit in the way of trading with each other in their own currencies. However, their central banks clear out their net exposures via the dollar every few months. No central bank wants to wind up holding a lot of a not-very-strong currency that has the potential to get weaker. Similarly, as we have been vividly with crypto, a big obstacle to establishing new payment systems is fraud. If you think centralized exchanges like FTX are problematic, expert contacts tell me that the decentralized crypto exchanges make centralized exchanges look like paragons of virtue.

The reason this matters is fraud detection and control is very much an economies of scale activity: the more you have seen, the more you know how to stop it without holding up legitimate transactions. The Visa and Mastercard networks have an enormous experience base. Catching up at a reasonable cost will not happen quickly.

00 Development and Change – 2023 – Chowdhury