Yves here. While this analysis is helpful and I assume directionally correct, it appears to omit a key source of energy loss of renewables: that of storage costs, as in moving energy in and out of batteries. That isn’t always necessary (think using solar panels for home power during the time of day when the sun is shining) but it should be included to make an apples to apples comparison. The article does mention battery conversion costs, but uses the most efficient type of batteries, large scale used at utilities, and does not mention the presumably less efficient ones used in residential and smaller industrial settings. Do readers have any data on those types?

By Karin Kirk, a geologist and freelance writer with a background in climate education. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

Traditional electricity generation has a thermodynamics problem: Burning fuel to generate electricity creates waste heat that siphons off most of the energy. By the time electricity reaches your outlet, around two-thirds of the original energy has been lost in the process.

This is true only for “thermal generation” of electricity, which includes coal, natural gas, and nuclear power. Renewables like wind, solar, and hydroelectricity don’t need to convert heat into motion, so they don’t lose energy.

The problem of major energy losses also bedevils internal combustion engines. In a gasoline-powered vehicle, around 80% of the energy in the gas tank never reaches the wheels. (For details, see an earlier post comparing the efficiency of electric vehicles and internal combustion engines.)

Fossil-fueled power plants are more efficient than a car’s engine, but they still grapple with the same obstacle. In both cases, converting energy from one form to another leaves only a fraction of the original energy left over to accomplish the intended task.

Traditional Thermal Power Plants Lose Most of the Energy Going into Them

Through the ages, the most common way to make electricity has been through thermal generation, with the process beginning by generating heat. That heat is then used to boil water and make steam, which spins a turbine that generates an electric current. The fuel source can be coal, natural gas, or nuclear fission, but the process is similar – and very inefficient. The majority of the energy that goes into a thermal power plant is vented off as waste heat. Additional minor losses come from the energy used to operate the power plant itself.

In contemporary thermal power plants, 56% to 67% of the energy that goes into them is lost in conversion. But the impacts of mining, processing, greenhouse gas emissions, particulates, and other forms of pollution are levied on the full amount of fuel consumed at the upstream end of the process, not just on the minority that eventually reaches your outlets. The same is true for the price tag, of course, which is all the more noticeable as the cost of natural gas is increasing.

How Do Sources Stack Up?

The efficiency of power plants is measured by their heat rate, which is the BTUs of energy required to generate one kWh of electricity. This simple math compares the total amount of energy entering the power plant with the amount of electricity that leaves the plant and heads out onto the grid.

The Energy Information Administration lists the heat rate for different types of power plants, and the average operating efficiencies of thermal power plants in the U.S. in 2020 were:

- Natural gas: 44% efficient, meaning 56% of the energy in the gas was lost, with 44% of the energy turned into electricity.

- Coal: 32% efficient

- Nuclear: 33% efficient

Efficiency of Renewables

What about the efficiency of renewables? A wind turbine is around 35 to 47% efficient. But wait, isn’t that the same low efficiency as coal and gas power plants? Well, yes…and no.

Comparing renewable energy with fossil fuels isn’t an apples-to-apples comparison, because renewables don’t use fuel.

A coal plant with 32% efficiency still burns 100% of its coal. The impact of burning coal is based on how much coal is burned, not how much electricity is generated at the end of the process. But a wind turbine that converts 32% of the passing breeze into electricity isn’t consuming anything.

Although wind turbines capture only part of the air moving past them, that’s not as problematic as the inefficiencies of fossil fuel plants, because the wind itself is free, nonpolluting, and is regularly supplied by the atmosphere. The same can’t be said for coal or gas.

Nevertheless, the more efficient a given wind turbine, the fewer of them that are needed. So efficiency does matter, albeit in a different way.

Solar panels range from around 18% to 25% efficiency, with steady gains in efficiencies in recent years. As with wind, the inefficiency of a solar panel doesn’t mean the Sun has to emit more energy to power the panel. But more efficient solar panels generate more electricity from each panel, which saves materials and land area.

Hydropower is the champion of efficiency, coming in at around 90% efficient at converting moving water into electrical current. Part of hydroelectricity’s impressive efficiency is that dams funnel water directly through turbines, whereas wind turbines simply sit in the midst of moving air and convert some of it to electricity.

Replacing Thermal Electricity Generation Cuts Overall Energy Consumption

Electricity generation accounts for 24% percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. An unsung benefit of replacing fossil-fueled thermal electric generation with wind, solar, or hydropower is that all of the fuel that ends up as waste heat simply doesn’t need to be replaced at all. More efficient methods of generating electricity renders the whole problem obsolete.

Consider a coal plant that consumes 1,000 megawatts of coal per hour and produces 320 megawatts of electricity per hour. It’s only the smaller number that needs to be replaced with a different source of energy. But that replacement would save 1,000 megawatts worth of pollution and fuel costs. Furthermore, switching to inherently efficient forms of energy means that less energy, overall, is needed.

Energy Losses Exceed Energy Uses

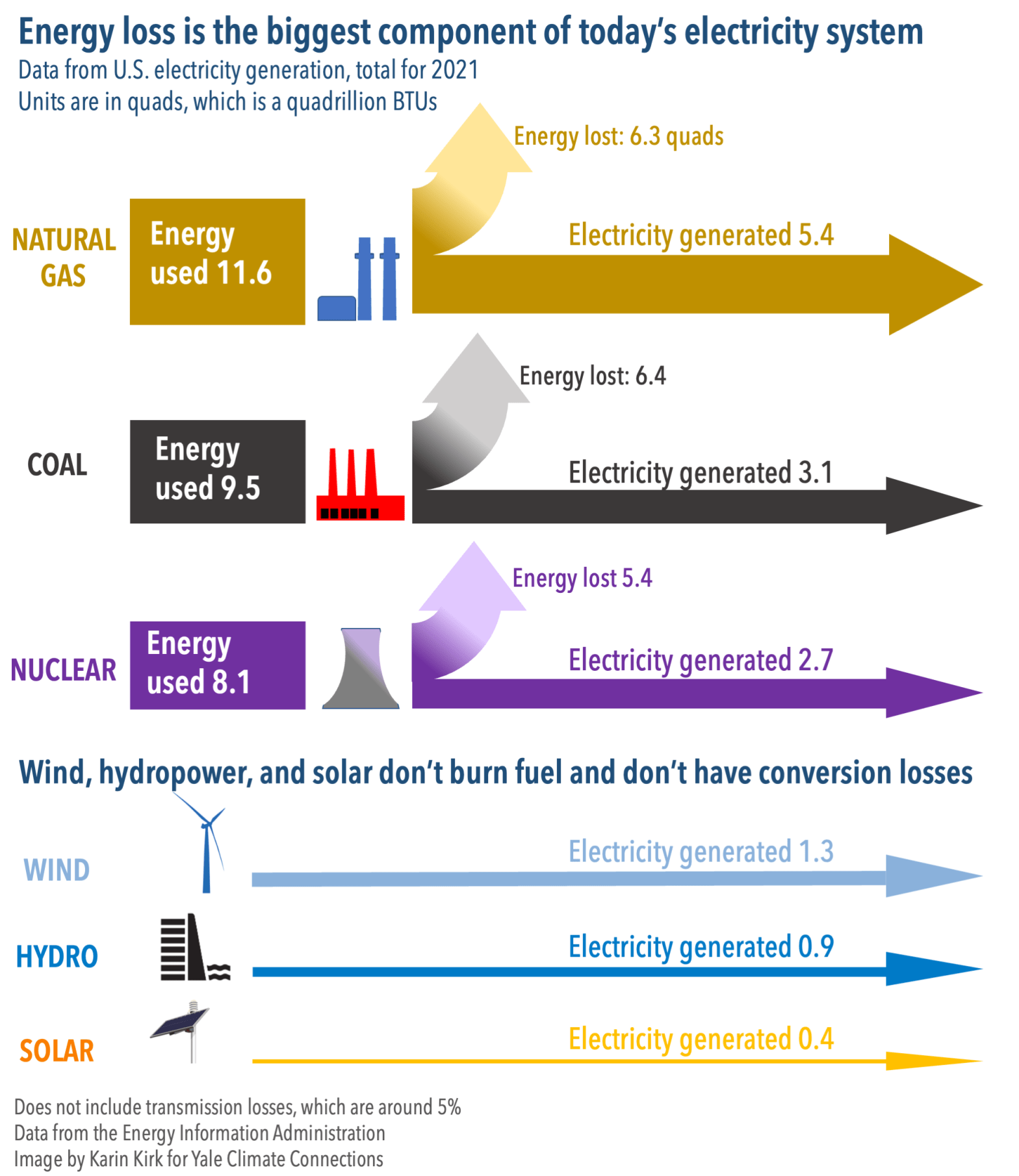

The figure below shows how energy flows through today’s U.S. electricity grid. This information is more commonly illustrated from the downstream end of the power plants, but by including all of the fuel that goes into the power plants, it’s easier to appreciate the magnitude of energy used throughout the entire process – and the massive amounts of energy that will be saved as coal and natural gas are replaced with renewables.

Using the above numbers from 2021, and considering the entire fleet of energy sources, more energy was lost in conversion than was turned into electricity. The largest component of today’s electricity system is energy loss.

Energy Transmission and Storage Cause Smaller Losses of Energy

Regardless of the source of electricity, it needs to be moved from the power plant to the end users. Transmission and distribution cause a small loss of electricity, around 5% on average in the U.S., according to the EIA. The longer the distance traveled, the more the loss of electricity from transmission lines, and this energy loss is the same no matter what type of energy feeds into the grid.

Energy storage is an increasingly common part of the electricity supply, and storage is an essential element of decarbonizing the electricity grid. How much energy do batteries lose? The round-trip efficiency of large-scale, lithium-ion batteries used by utilities was around 82% in 2019, meaning 18% of the original energy was lost in the process of storing and releasing it. Batteries are getting more efficient over time, and the Department of Energy’s grid storage research uses a battery efficiency of 86% in its estimates.

A Better Way

Because fossil fuels have been the norm for most of the world’s energy for over a century, the thermodynamic challenges of burning fuel have long been accepted as an inevitable side effect.

The Energy Information Administration euphemistically describes these energy losses as “a thermodynamically necessary feature” of thermal electricity generation.

But as the world looks to re-shape the energy supply, major losses of energy are neither necessary nor a feature of modern electricity. A cleaner, and leaner grid could lower overall energy consumption, produce less pollution overall, and emit far less climate pollution. One might consider these improvements to be the critically “necessary features” of tomorrow’s energy system.