Yves here. KLG reviews a paper, admittedly based on mouse studies (but for this purpose mice are good proxies), that finds that repeated, or using the apparent term of art, extended use of Covid boosters is counterproductive.

By KLG, who has held research and academic positions in three US medical schools since 1995 and is currently Professor of Biochemistry and Associate Dean. He has performed and directed research on protein structure, function, and evolution; cell adhesion and motility; the mechanism of viral fusion proteins; and assembly of the vertebrate heart. He has served on national review panels of both public and private funding agencies, and his research and that of his students has been funded by the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and National Institutes of Health.

Vaccines have, so far, played the central role in our response to COVID-19. However, their success remains a matter of some dispute. Most of the vaccines authorized under the Emergency Use Authorization of the World Health Organization have been directed at the Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) of the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2) [1]. The original vaccination plus one booster shot elicited a strong immune response to what has become known as wild-type SARS-CoV-2. Multi-inoculation vaccine protocols consisting of 2-3 shots are common and generally work well, for example against Hepatitis B and several common “childhood diseases.”

The challenge with COVID-19, however, is the continual emergence of dominant variants as SARS-CoV-2 evolves as it moves through the human population [2]. The appearance of the Omicron variant (and others) led to the use of additional booster shots. Nevertheless, immune protection after the initial booster shot declines with time. This heightens the risk of infection from emergent SARS-CoV-2 variants. Over the past two years, it has become clear that the COVID-19 vaccines currently in use do not work as we have come to expect of vaccines. It has also been understood for a long time that lasting immune responses to coronaviruses are rare, but this seems to have been forgotten in the case of COVID-19. These vaccines prevent neither infection nor transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

To simplify complex immunology, vaccination leads to the production of B cells in germinal centers in the spleen and the secretion of antigen-specific antibodies by these cells (humoral immunity mediated by circulating antibodies). This is followed by presentation of processed viral antigens on the surface of T cells, which when activated kill the virus by a cell-mediated mechanism (cell-mediated immunity). A question that has not been fully addressed is whether extended vaccination against COVID-19 will reestablish protective immunity, such as it exists, or alternatively lead to immune tolerance in which the immune system “ignores” the virus. Yes, it has been pointed out by our healthcare leaders during the pandemic that vaccines are not absolutely effective, and vaccinated people occasionally catch a disease against which they have been vaccinated. However, multi-boosted people often come down with COVID-19 and this indicates something is amiss somewhere. Perhaps so many “breakthrough” cases are not stochastic or “accidental.”

A paper published in December 2022 addresses this conundrum and concludes that repeated vaccination with boosters against SARS-CoV-2 may not be a good idea, as stated in the title: Extended SARS-CoV-2 RBD booster vaccination induces humoral and cellular immune tolerance in mice. I am not now, nor will I ever be an immunologist, but as an interested biomedical scientist I find the data presented here clear and accessible. They support the conclusions of the authors, in a similar manner to those in the research covered here previously on COVID-19 vaccine mandates and the incidence of injuries attributable to COVID vaccines (a topic that remains understudied in my view). I have included parts of Figures 1-4 below that illustrate the results of this research and support the conclusions; each figure is available at the link. Reports of COVID-19 research often leave out detail that allows the reader to understand the results and conclusions. The data shown here are no more complicated that the typical analysis of the economy, even if they are not often considered among the public at large. The other data reported in this paper are consistent with these examples.

- Extended immunization did not enhance RBD-specific antibody production in mice. The experimental strategy of this research is illustrated in Figure 1. BALB/c mice were inoculated with vaccine four times over six weeks to represent the conventional immunization (control) and six times over 12 weeks in the extended immunization (experimental). After reaching a peak with inoculations 3-4, the antibody titer [3] for RBD-specific antibody declined in the extended/experimental branch of the experiment relative to the conventional/control branch. Note that the y-axes are on a logarithmic scale with each division representing a 10-fold difference, which means the declines in antibody titer after extended vaccination are substantial (center and right panels). PBS is an abbreviation for phosphate-buffered saline solution, which is the inert “vehicle” used in these experiments.

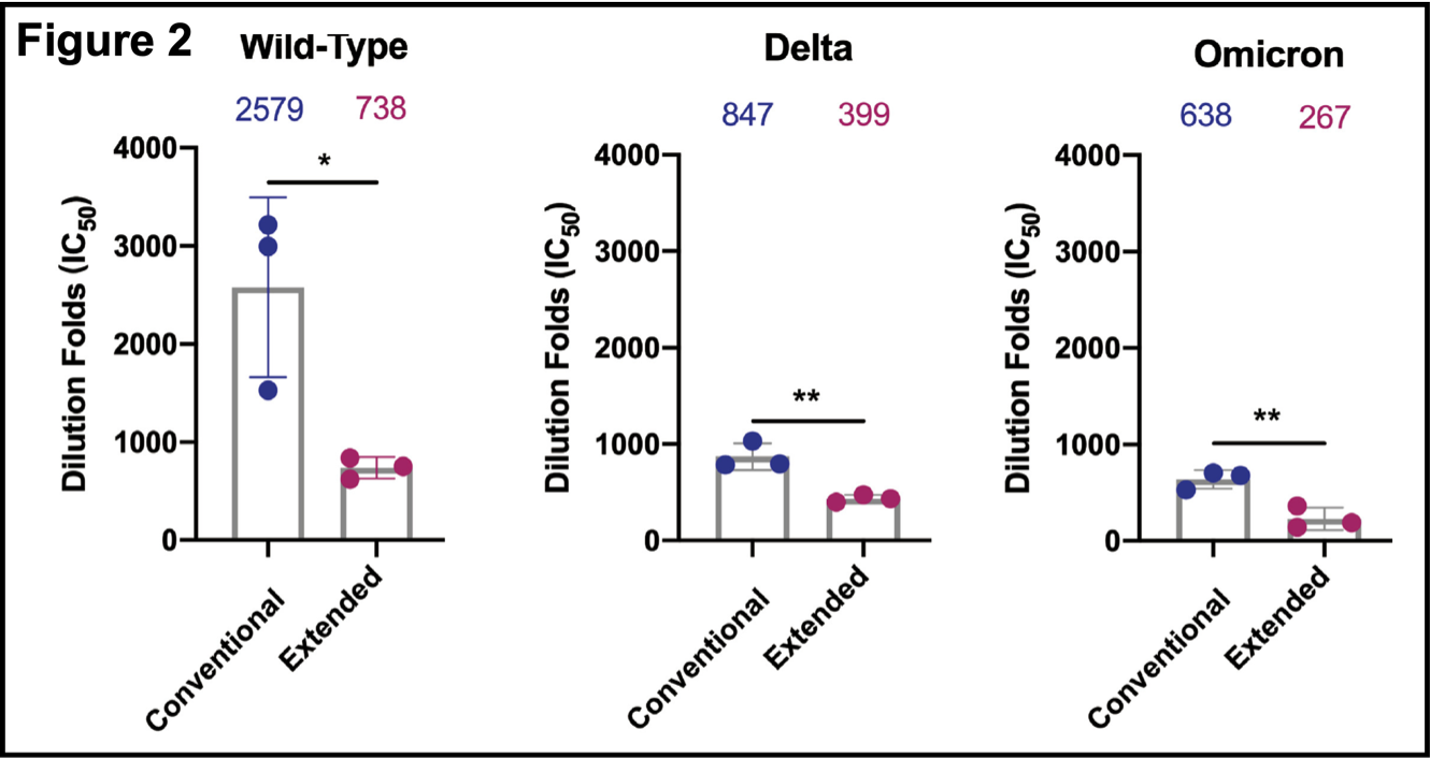

- Extended immunization reduced serum neutralizing antibody responses (Figure 2). Pseudovirus (and inactive virus) neutralization curves (not shown; available here) for the original wild-type, and Delta and Omicron strains were determined. Assays were completed 10 days after the final dose of vaccine, which is a standard condition for these and similar experiments. Antibody responses were higher with wild-type virus than with Delta or Omicron. In all three cases, the response was less in the extended immunization branch. These results show that the Spike RBD protein construct used here produces a neutralizing antibody response in BALB/c mice against SARS-CoV-2. Extended immunization attenuates this activity, however.

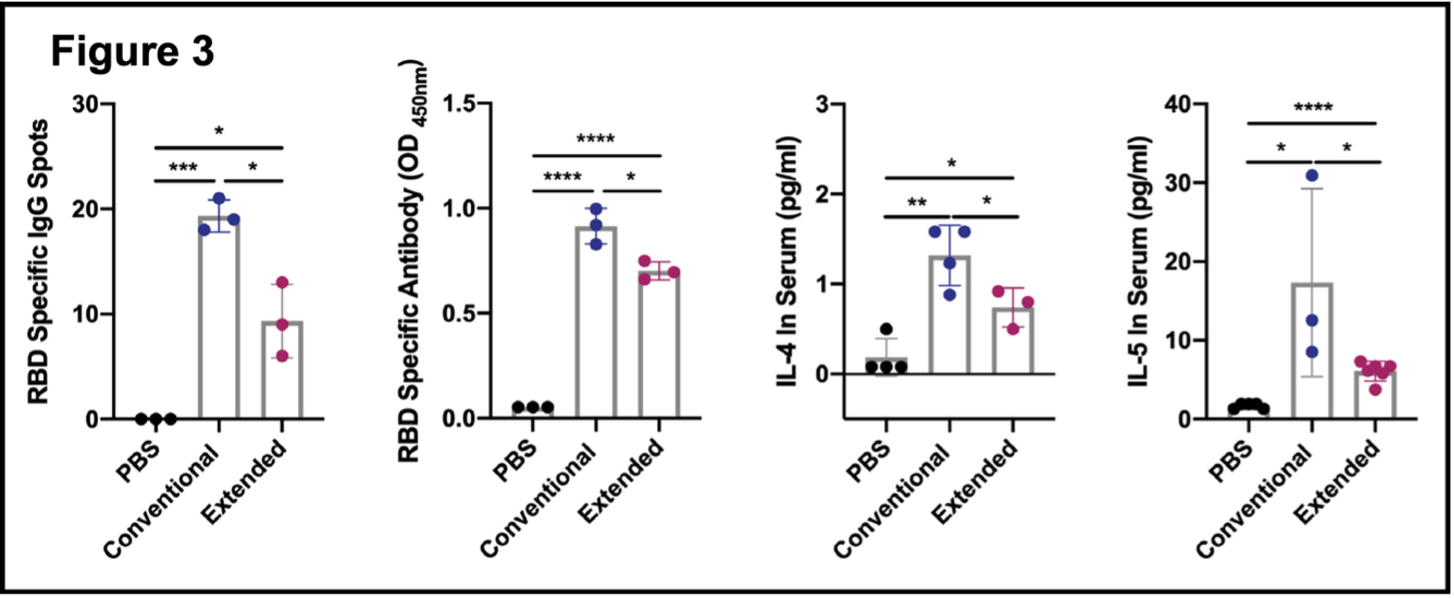

- Extended immunization inhibited the production of RBD-specific memory B cells. Total lymphocytes were analyzed one week after final injections in each group. Relevant markers for plasma cells and memory B cells showed that these were elevated in both groups (Figure 3AB, flow cytometry). The right panels show that each cell population is elevated in the conventional vaccination group compared to the extended vaccination group. This is consistent with previous results showing that extended vaccination attenuates the immune response to SARS-CoV-2. Figure 3 (excerpt below) shows that levels of memory B cells (as RBD-specific IgG spots)

are higher in the conventional versus the extended immunization (panel 1) and that RBD-specific antibody (measured in an antibody assay) is present in both samples but significantly less in the extended branch (panel 2). B cell proliferation and differentiation are promoted by the cytokines interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-5 (IL-5). Both are elevated in each branch of the experiment, but both are reduced in the extended vaccination (panels 3 and 4). These results, taken together with those presented in Figures 1 and 2, indicate that COVID-19 vaccine boosters diminish RBD-specific humoral immunity and may promote immune tolerance of the RBD Spike protein and consequently of SARS-CoV-2.

are higher in the conventional versus the extended immunization (panel 1) and that RBD-specific antibody (measured in an antibody assay) is present in both samples but significantly less in the extended branch (panel 2). B cell proliferation and differentiation are promoted by the cytokines interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-5 (IL-5). Both are elevated in each branch of the experiment, but both are reduced in the extended vaccination (panels 3 and 4). These results, taken together with those presented in Figures 1 and 2, indicate that COVID-19 vaccine boosters diminish RBD-specific humoral immunity and may promote immune tolerance of the RBD Spike protein and consequently of SARS-CoV-2.

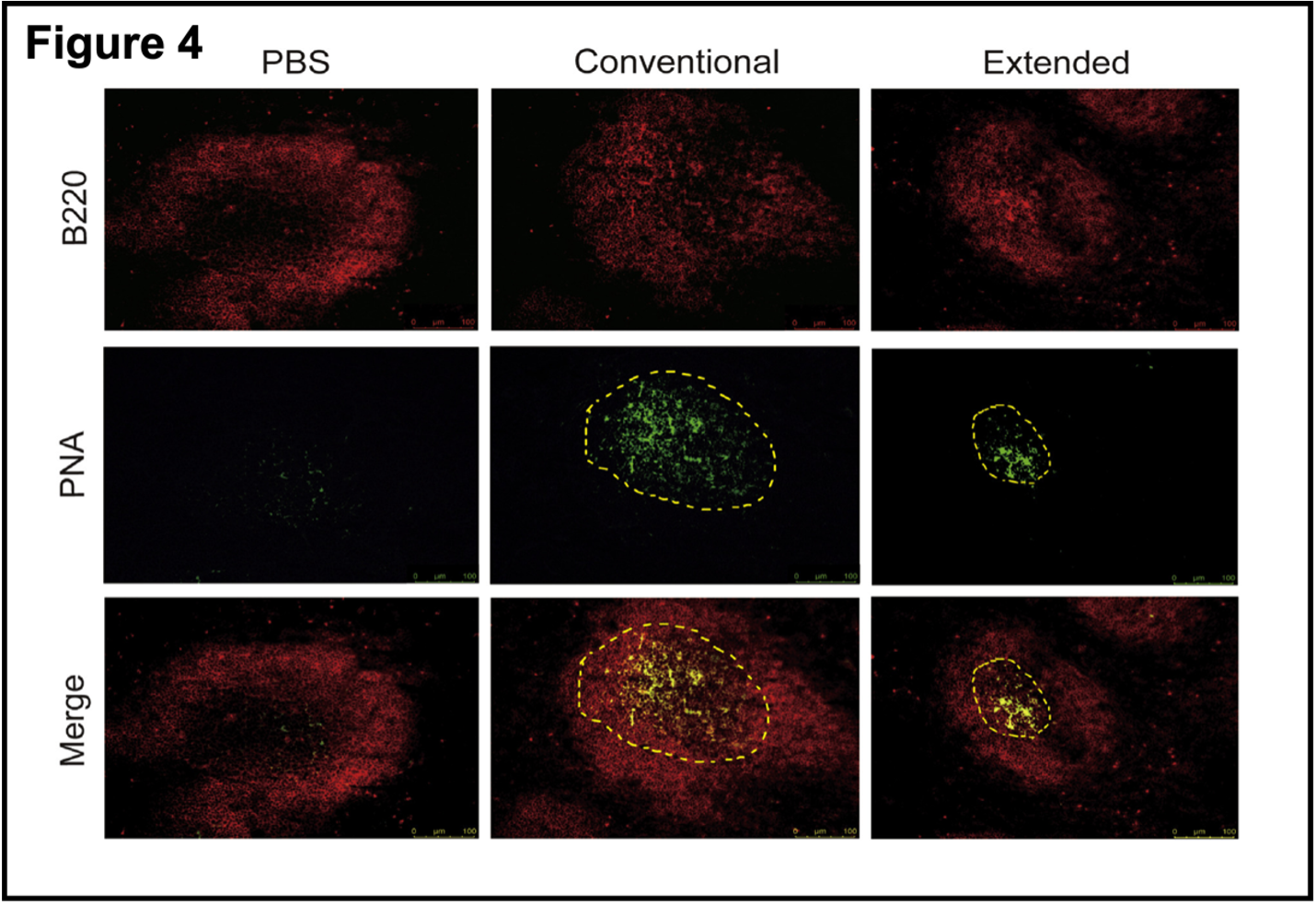

- Extended immunization suppressed the formation of the germinal center. After antigen exposure, activated antigen-specific B cells cause a cascade of events that lead to the formation of germinal centers in the spleen. B cells in the germinal centers develop into memory B cells and plasma cells that are essential for effective, long-lived humoral immunity after exposure to an antigen (vaccine or natural exposure). Figure 4 shows that extended immunization suppressed the formation of the germinal center.

Staining with specific reagents shows there is no germinal center in the PBS control and that the germinal center after conventional vaccination is much larger than after the extended vaccination protocol. Without going into the details of immunofluorescence, the yellow dots in the merged green and red panel confirms the presence of the germinal center. These results are strong support for the hypothesis that RBD boosters after a conventional course of vaccination interfered with germinal center responses to the antigen. This again supports the idea that multiple boosters using the RBD domain of the Spike protein could induce immune tolerance rather than immune responses to the antigen/virus. What about the other “half” of the immune response, T cell-mediated immunity?

Staining with specific reagents shows there is no germinal center in the PBS control and that the germinal center after conventional vaccination is much larger than after the extended vaccination protocol. Without going into the details of immunofluorescence, the yellow dots in the merged green and red panel confirms the presence of the germinal center. These results are strong support for the hypothesis that RBD boosters after a conventional course of vaccination interfered with germinal center responses to the antigen. This again supports the idea that multiple boosters using the RBD domain of the Spike protein could induce immune tolerance rather than immune responses to the antigen/virus. What about the other “half” of the immune response, T cell-mediated immunity?

- Extended immunization inhibited the activation of CD4+T cell immune response. This is a continuation of the theme. Figure 5 shows that both courses elevated T-cell markers (CD69, CD137) [4] but that once again, levels of each marker are higher in the conventional vaccination versus the extended vaccination (bar graphs of the right panels in Figure 5A,B, similar to those shown above; the data are convincing). What is particularly interesting is the evaluation of T cell exhaustion markers in this analysis, which are increased in the extended set (PD1+, LAG-3+, Figure 5D. T cell exhaustion, which has been discussed during the pandemic, would cause attenuation of cell-mediated immunity.

- Extended immunization inhibited CD8+ T cell-mediated immune response. This was demonstrated in the final set of experiments presented (Figure 6). This is another complicated composite figure but shows by several complementary measures that prolonged immunization with RBD boosters may lead to reduced CD8+ T cell activation and increased T cell exhaustion. Thus, by the mechanisms identified here, both B cell-mediated humoral immunity and T cell-mediated immunity are impaired in this experimental model of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Which brings up the question of whether this mouse model can be generalized to human biology. This is a perpetual and perennial concern in biomedical science. Another group has shown that the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in BALB/c mice is similar to that in humans (Nature, open access). This is not unexpected, but more generally, the appropriateness of an experimental model depends on the question(s) asked. At the cellular and immunological levels, mice and humans are very similar. The same consideration extends even further. A vertebrate cardiomyocyte is a vertebrate heart cell and primary chicken cardiomyocytes have been very useful and understanding the assembly of heart muscle. The biochemistry, cell biology, and electrophysiology are very similar and generalizable, even though the chicken heart has three chambers instead of the four-chambers in the mammalian heart. Primary chicken heart cells can also be cultured from a fertilized hen’s egg and are therefore much cheaper and easier to use than primary human heart cells. Moreover, as a practical matter, until the egg hatches the researchers are not working with vertebrate animals and, speaking from personal experience, life is much easier on all fronts. In any case, where would the primary human heart cells come from? Perhaps from inducible pluripotent stem cells in culture, but while much progress has been made with stem cells, they remain finicky and expensive.

So, what has been accomplished here? In the words of the authors (lightly edited with slightly different emphases):

We have characterized the effects of extended immunization with RBD booster vaccines in a mouse model. Our findings revealed that repeated dosing after the establishment of a vaccine response might not further improve antigen-specific reactivity and persistence. Rather, it could cause systematic immune tolerance and the inability to generate effective humoral and cellular immune responses to current and future SARS-CoV-2 variants. Our study provides timely information related to the prevention of COVID-19 transmission and illness. Our results also show that an extended immunization course with two or more RBD-based vaccine boosters is likely to be problematic.

What I know is that multiply boosted people get COVID-19 often despite their “vaccination status.” The latter is a protean term. Sometimes unvaccinated status means two shots, sometimes four shots. And sometimes it simply means that the electronic medical record (EMR) consulted by the healthcare professional is simply wrong [5]. This is not how vaccines are supposed to be described, and something is going on, somewhere.

Finally, this paper illustrates much about how biomedical research is done. For a long time, I have read the acknowledgments of a scientific paper immediately after reading the Abstract/Summary. And sometimes I stop right there. Who and what supported the research has become increasingly relevant to how the work should be viewed. I also pay some attention to the “journal” in which the work is published, but that is a story for another time, one that is important to the COVID-19 literature, which on 21 August 2023 has 376,083 entries since late 2019, or more that 8,000 scientific papers per month since the start of the pandemic. Not hardly, as they say in these parts. And much of the COVID-19 literature has been peer reviewed on the fly. The present paper is published in iScience, which is an open access “imprint” of Cell Press. The publication is authoritative based on history going back nearly 50 years to the first publication of Cell. Still, all scientific papers should be read with one’s spidey sense on alert.

But back to how this research was funded. A group of 17 scientists at Chongqing Medical University was supported by the SARS-CoV-2 Virus Emergency Research Project at Chongqing Medical University. They declared no competing interests. They produced a study that is quite good in my view, although it could have used an editor in places (as can we all) and one can always imagine other experiments that might have been done differently. I suspect the only thing the group leaders had to do was write a short application explaining what they planned to do and why. No “generation of preliminary data” followed by six months writing a grant application for a deadline that is nine months away. And then no waiting another 4-6 months for a “funding decision” that is most likely to be an inscrutable “thanks, but no; don’t call us and we’ll not call you.” Despite questions about the origin of SARS-CoV-2, and an accidental lab leak seems plausible to me, that this group from one university published this paper quickly and without too many hoops to jump through bodes well for the future of Chinese science. It is also a baleful omen for the future of science in the United States and perhaps other so-called allied nations. Something to keep in mind.

Notes

[1] The construction of the proper constructs for the Spike protein mRNA vaccines considered previous research on the Zika virus vaccines. Whatever the ultimate success of the COVID-19 vaccine strategy, this strategy avoided mistakes with the original Zika vaccines that to my knowledge are not yet ready for use in human populations. The technical facility with which COVID-19 vaccines have been developed as experimental approaches to the pandemic is not in doubt. Whether they work as we have come to expect of vaccines is another matter altogether.

[2] SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus and evolves more rapidly than DNA viruses, primarily because RNA replication is more error-prone than DNA replication.

[3]. Antibody titer is a measure of the dilution at which specific antibody can be detected. The larger the dilution that produces a signal in the assay, the more active the antibodies are in the sample.

[4] CD: Cluster of Differentiation. These are cell-surface proteins that can be used to identify distinct cells of the immune system, which are usually indistinguishable using light microscopy. Each protein has a specific function, although some remain obscure. Last time I looked at the large table in a neighbor’s laboratory, there were more than 300 such “CD” markers (current list is here; concise descriptions of the cells mentioned in this research are included:

CD4: A co-receptor for MHC Class II (with TCR, T-cell receptor); found on the surface of immune cells such as T helper cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Used by HIV to enter T cells: in HIV infection. CD8+cytotoxic T cells recognize and kill infected cells hence they are predominantly for protection against intracellular pathogens, e.g. viruses, and some bacteria, i.e. Rickettsiae.

CD8: A co-receptor (with TCR, T-cell receptor) for MHC Class I; mostly found on cytotoxic T cells, but also on natural killer cells, cortical thymocytes, and a subset of myeloid dendritic cells. In HIV infection, CD8+ cytotoxic T cellsrecognize and kill infected CD4+ helper T cells, which are critical for the body’s immunity. In HBV infection CD8+cytotoxic T cells are involved in liver injury by killing infected cells and by producing antiviral cytokines capable of purging HBV from viable hepatocytes. There are two isoforms of the protein, alpha and beta, each encoded by a different gene (below).

CD69: An early activation marker on T cells and NK (natural killer) cells.

CD137: Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 9 (TNFRSF9), a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family, also known as 4-1BB and Induced by Lymphocyte Activation (ILA). Targeted by Bristol Myers‘ Urelumab, a CD137 agonist antibody, in early trials with anti-PDL1 (CD274) mAbs; activating CD137 stimulates an immune response, in particular a cytotoxic T cell response, against tumor cells, though liver toxicity can be a problematic side effect. Pfizer also has an early-stage 4-1BB agonist (Utomilumab PF-2566) in combination trials, and Pieris is trialling PRS-343, a CD137 – HER2 bispecific (2016).

The most common markers are easily identified using specific antibodies that are commercially available for use in cell sorting/counting (the blotches in the figures in this paper).

[5] EMR are designed for (mis-)management of billing, not healthcare.