EDITOR’S NOTE: USA TODAY does not name victims of sexual violence. Massage workers in this story are referred to by their spa nicknames or their initials.

Shirley had been in Baltimore for only a few weeks when she was arrested. She mostly remembers how loud the police were. How rough.

She was living and working at a house being used for illicit massage. That night the boss sent her to a hotel on an “outcall” – bringing sexual services to a customer. The customer turned out to be an undercover officer.

Shirley’s husband had pressured her into taking the job. She thought she’d be working as a masseuse. Instead, she had to perform sex acts for men who rang the doorbell at all hours. She didn’t want to. But the boss would know if she didn’t. And she couldn’t imagine how to leave, or what her husband would do if she came back home.

As scared as she was of the two men who had trafficked her, Shirley was even more terrified of the burly police officers who showed up in February 2014.

“I didn’t know where they were taking us. I didn’t dare to talk to them, and didn’t dare to say that my ex-husband forced me to go to this massage parlor,” she told USA TODAY in her native Mandarin.

“At that time, I was thinking ‘Life is terrible,’ and tears were falling uncontrollably. And I was thinking, ‘It would be best if I could die now.’”

The Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act was supposed to help women like Shirley, many of them new – and sometimes undocumented – immigrants. Congress intended the law to be comprehensive: It strengthened punishment for traffickers, created task forces and provided assistance for victims in the form of visas and restitution. It also established a definition for sex trafficking: causing a person to engage in commercial sex through force, fraud or coercion.

Yet law enforcement and prosecutors struggle to build cases that lead to convictions. Police often rely on victims to say they’ve been forced and to identify perpetrators – which has proven an unrealistic expectation. Prosecutors tend to settle for plea deals on related charges – pimping, pandering or money laundering – with lesser sentences.

More than two decades after the law took effect, women are still being trafficked all across the U.S. It takes many forms. One of the most organized – and lucrative – is through massage, where traffickers are typically of Asian descent, with a variety of business models.

No one really knows how many people are trafficked in the United States. The National Human Trafficking Hotline attributes hundreds of cases a year to the massage business, but that counts only victims who call the hotline or cross paths with law enforcement or advocates.

Failures by police – and society – to identify women working in sex spas as victims has clouded the picture and helped allow the crimes to continue.

Even though officers have become increasingly aware of the complexities of this type of trafficking, some continue to arrest women ensnared in the illicit massage business. Traffickers have seized on confusion over whether the women are victims or consenting sex workers – or both – and adapted their methods of control, which makes trafficking harder to detect and prove in court.

All of which helps keep their experiences hidden. Stories of sex trafficking often are filled with details of police raids, angry neighbors, arrests and sometimes advocacy groups. Rarely are the victims the center of coverage. This story, based on interviews with survivors and experts, and more than 50 criminal and civil cases, is about them.

Combined, their accounts reveal sophisticated and evolving tactics that begin at recruitment and continue inside massage rooms, hotel rooms and bedrooms. USA TODAY found traffickers stay one step ahead of anti-trafficking laws primarily by manipulating the women, who are:

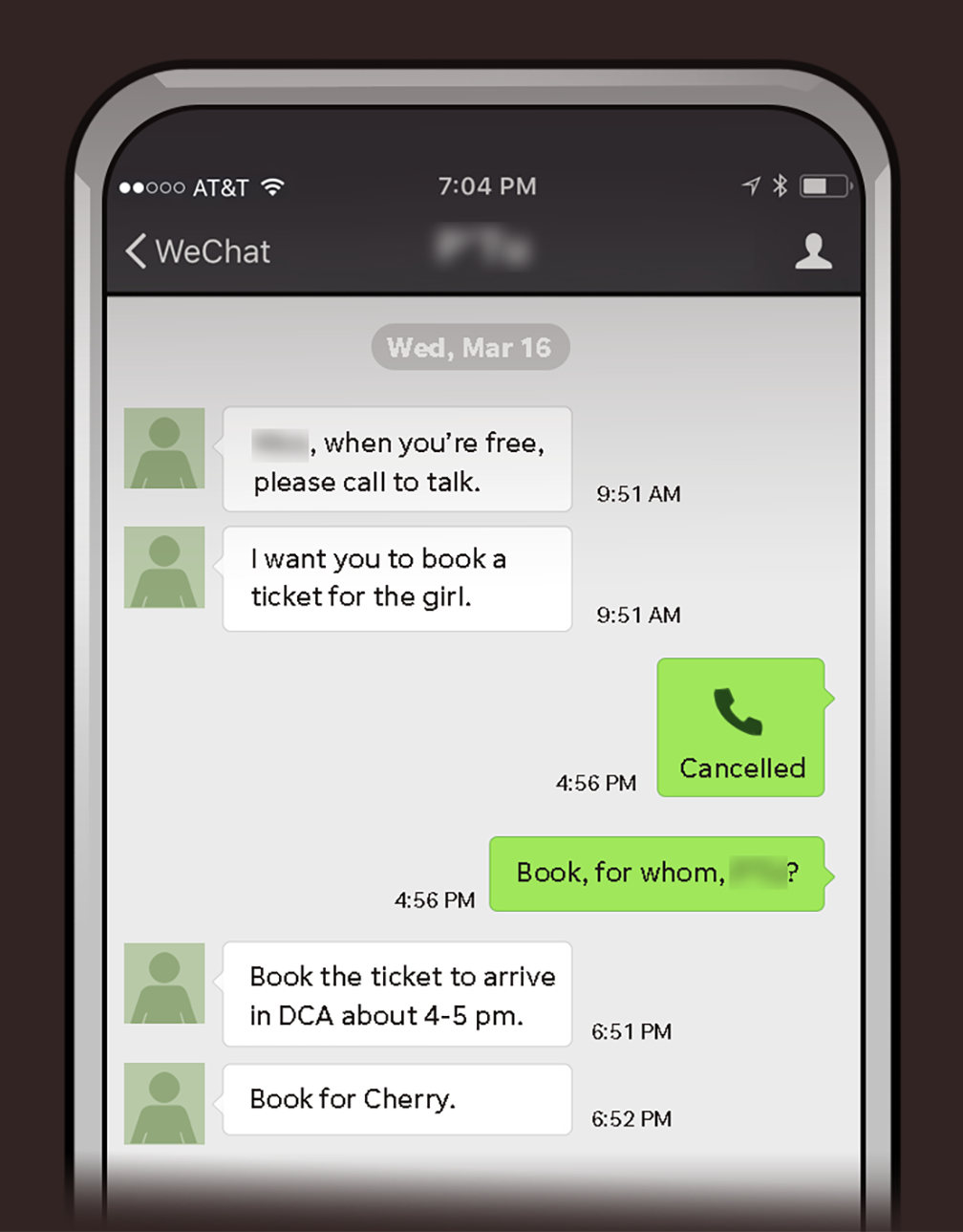

- Recruited via hard-to-track apps like WeChat. Fake accounts and group chats conceal their traffickers’ identities and can be deleted on the spot if the traffickers catch wind of police investigations. That leaves victims no evidence of who recruited them to share with authorities.

- Expected to perform sex acts in apartments, rental houses and hotels instead of – or in addition to – spa storefronts. Those locations are less obvious to authorities and keep victims more isolated.

- Manipulated to believe they’re willing participants. Traffickers concoct elaborate stories to justify withholding their passports and present the jobs as the only way for them to pay off heavy debt incurred for travel to the U.S. Traffickers often tell them they’re free to leave, information police may take at face value.

- Made to work in violent environments where traffickers may turn to customers or hired guns for beatings and assaults. That allows traffickers to distance themselves from the violence and leaves investigators and prosecutors at a loss to figure out whom to blame.

Reye Diaz, a retired special agent with California’s Department of Justice, said he saw a significant shift from the old days when trafficking rings used physical force to hold victims captive.

“When the laws changed on trafficking, a lot of criminal syndicates became aware of it,” Diaz said. “These girls aren’t being forced in that old way because the traffickers know they’ll get busted.”

Shirley is one of the few to get out quickly, though the details of her escape are blurred by the trauma of the experience. She remembers being held in jail overnight. Being picked up by the driver who took her on outcalls. Going back to the house. Collecting her few belongings and persuading the boss to give her back her passport, saying she needed it to get a lawyer to fight the charges.

She also remembers borrowing money – probably from the driver – because she didn’t have any of her own. She bought a bus ticket and returned to New York. There, she got a new phone and number, left her husband and found help through social workers who connected her to a nonprofit advocacy group.

Discussing the experience still makes her nervous. Even years later, in a secure location, Shirley is cautious. Her sleek black hair and professional clothes add to her resolve that breaks only when she mentions her child.

In some respects, she explains, leaving was easier than what came next: rounds of intensive therapy to stop blaming herself. The realities of being a single mom, thousands of miles away from family. Crowded women’s shelters. Food stamps and credit card debt. Social stigma, racism and language barriers.

“It was way more difficult than I thought for women trapped in the illicit massage industry to leave the industry completely and survive,” she said. “I felt my heart was broken into pieces.”

Shirley met the man who would become her husband in China. He had U.S. citizenship, she said, and was traveling back and forth between the two countries. After they were married in 2011, she moved with him to New York.

That’s when she said the indoctrination began. He kept her isolated, forbidding her from befriending other members of the Chinese diaspora. He pushed her to get a massage job. He was a driver for people in that world and told her she could make a lot of money.

Two months after she arrived in this country, Shirley found out she was pregnant. She stayed home with the baby until her husband’s pressure grew too strong to resist.

“I felt brainwashed by him,” Shirley said. “He was constantly telling me: ‘Go and make money. This money is easy; it’s not that dangerous.’”

When he shared an ad for a massage job in a Chinese-language newspaper in early 2014, Shirley agreed. It was vague, she remembered, not saying much about the position, only that it was safe. It said nothing about sex.

Looking back, Shirley wonders if her husband intended to pimp her all along.

“He has always been someone who wants to earn quick money,” Shirley said. “Maybe he had such an idea since the beginning, already calculated, just finding a time to exert more pressure on me.”

Her situation is not uncommon. According to a Human Trafficking Institute analysis of cases active in 2020, victims knew their traffickers at least 43% of the time.

Victims in illicit massage and related industries are often recruited from home countries in Asia, or shortly after arriving in the U.S. The process may begin innocuously. A friend knows someone who knows about good-paying jobs.

“It’s all about who you know,” said Panida Rzonca, who works with the Thai Community Center, a service provider that assisted victims in a landmark 2019 sex trafficking case out of Minnesota. Thirty-seven defendants were convicted or pleaded guilty to sex trafficking or related charges. The final defendant pleaded guilty in late November.

Recruiters also know each woman’s vulnerabilities – and use them. An FBI agent who worked on the Minnesota case described it to jurors as “selling the dream.”

“What that is is providing someone the opportunity to escape their current situation, which is oftentimes bad, for promises of a better life,” Special Agent Ryan Blay said in court testimony. “In the investigations I’ve conducted and overseen, you see promises of wealth, you see promises of travel, you see promises of love, you see promises of education, you see promises of material goods and housing. It basically runs the gamut.”

Victims are told by friends, family and even pop culture that the U.S. is a land of opportunity. Some are tempted by visa brokers or human smugglers who arrange entry into America for a fee. Others are deceived directly by traffickers who own their debt and force them to work to pay it off.

USA TODAY found several cases illustrating how far traffickers will go to game the visa system. In the Minnesota case, which authorities said was one of the largest sex trafficking rings ever dismantled by the federal government, several victims agreed to testify, offering a rare glimpse into the shadowy world.

Jenn took the stand for hours. She told jurors she was the oldest of three girls, the daughter of a farmer and construction worker in northeast Thailand. They were poor, she said, even before her mother died when she was 18, leaving Jenn to care for her sisters.

She worked at a bakery making about $200 a month – not enough to cover food and school tuition. From there she went to a karaoke bar where she’d occasionally have sex with the customers to boost her earnings. The work was on her terms – she set the price, chose the customers, controlled the conditions.

Yet she felt unhappy and stuck. She’d had a daughter and split with the father, who had taken the baby abroad with him. That’s when she met the friend of a relative who put her in touch with a broker.

The broker, whom she called Ton, said it was much easier overseas. They’d start with a visa application. For that, Ton needed all of her personal information: address, house registration, passport, bank account, her daughter’s birth certificate.

He put money in her account to make it seem as if she was a wealthy traveler. He concocted a story about a vacation to Florida with her baby and baby’s father. Ton and another woman, called Tuk, coached Jenn through the visa interview process. They told her to dress professionally, to wear glasses to look intelligent.

Jenn said she knew she’d owe money for all of it. She didn’t know until after she got to Minneapolis that the trafficking organization would charge her $60,000, or that they intended for her to repay it through sex work.

She also knew little about them, only that the woman who owned her debt was M.

M called Jenn’s cellphone when she landed and told her to check into a hotel, then take a taxi to Walmart to buy condoms and lubrication. She didn’t know where to find the items; she barely spoke English. M called her stupid and yelled at her.

The next day, her first day working, M sent 10 men to have sex with her. While on the stand, the prosecutor on the case asked Jenn if she wanted to have sex with the men. She said no.

“How did it feel physically to you?” the prosecutor asked.

“It was, I was painful all over inside. It was bruised all over,” Jenn said.

“How did it feel emotionally?”

“I felt really bad.”

“Why didn’t you stop it?”

“I had to pay off my debt.”

A few ads like the one Shirley’s husband found in the newspaper still run daily in outlets like the World Journal. They say: “Hiring for a massage parlor” and include a phone number.

A decade ago, experts say, there would have been dozens of ads, similarly inconspicuous and short on details. Traffickers have always disguised their operations to avoid suspicion. Advances in technology have made that even easier thanks to difficult-to-trace apps like KakaoTalk, Line and WeChat – now the predominant means of recruitment.

“WeChat has become the end-all be-all,” said Chris Muller-Tabanera with The Network, an anti-trafficking organization that tracks ads for massage jobs and other data.

Launched in 2011 by Chinese tech giant Tecent, WeChat has more than 1.2 billion users . The mega-platform combines the functionality of FaceTime, WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, Uber, Paypal, even Tinder.

The application is extremely important to the Chinese community. Average Chinese users are glued to the app whenever they use their phones, according to Julie Yujie Chen, co-author of “Super-sticky: WeChat and Chinese Society.”

Part of the appeal is ease of use and registration. All you need is a phone number.

“Its ubiquity among domestic Chinese and Chinese diaspora and multi-functionality … make WeChat a handy tool that helps evade regulation and oversight in the illicit business such as transborder sex trafficking,” Chen told USA TODAY via email.

KakaoTalk is a similar app developed by a Korean company. It boasts hundreds of millions of registered users. Line is another major competitor app out of Japan.

Mentions of all three pop up frequently in recent illicit massage cases.

A friend introduced Q.D. to Mei Xing through WeChat in early 2017. Xing owned a trio of spas in Los Angeles. They were good places to learn about the massage industry, the friend said.

Q.D. said Xing recruited her to work at Sunshine Massage, according to court documents. She thought she was applying to be a massage therapist. She gave basic massages for the first few days after she was hired. Then Xing said Q.D.’s next customer would be a cop, and “whatever the customer tells you to do, do it.”

The customer forced her into oral sex, holding her down. She didn’t have a massage license and feared she’d get arrested if she stopped him.

According to a criminal complaint in the ongoing case, investigators couldn’t determine whether the man was a member of law enforcement, but they accused Xing of using the threat of arrest to coerce victims into sex acts as part of a trafficking scheme.

In another case, Chinese women with huge debts from traveling to the U.S. were lured into spas in Maine and New Hampshire via WeChat. Through messages in the app, Shou Chao Li and Derong Miao, the husband and wife who owned the spas, promised the women they’d make hundreds of dollars a day, according to a 2018 indictment. In reality, “this inaccurate and inflated figure did not incorporate operating costs and payments that were expected to be made.”

Li and Miao pleaded guilty to charges of interstate transportation for prostitution and were sentenced to roughly two years in prison. Sex trafficking charges against them were dismissed as part of a plea agreement.

Traffickers also turn to WeChat to operate their businesses.

A 20-count federal indictment unsealed in April charged nine people with violently attacking trafficking victims and running their nationwide enterprise from Queens via WeChat. They are accused of using the app to orchestrate the assaults, requiring videos of the beatings as proof.

They also are accused of sending instructions through the app to victims on where they’d be working and how much money to charge for sex acts. They allegedly arranged appointments via group chats with the victims, dispatchers and bosses.

Reye Diaz, the retired agent with California’s Justice Department, said he has seen traffickers use the app to communicate with customers as well, including marketing women.

“They’ll say ‘New car at house,’” Diaz said, of slang used by traffickers to conceal evidence of prostitution. “A lot of times they’ll put these little flags of what country of origin these girls are from, or they’ll send photos of the girls to the customers if they feel really comfortable. The girls are in these provocative poses and clothes.”

Functionality within WeChat can make it harder for victims to know who recruited them or the identities of ringleaders.

The app has a way to create large groups, like old-school chat rooms crossed with Facebook pages. That’s where many women are directed to find postings about jobs.

Susan Chang, a senior program manager for human trafficking intervention at the nonprofit Garden of Hope, said WeChat makes it so easy to connect that victims may not really know the person who told them about the group or who connected them to a trafficker on the platform.

“Oftentimes, I wonder,” Chang said, “do you really know who they are?”

Chang said she has seen cases when traffickers watch over spas remotely via security systems. If they see police arrive, they’ll block victims on WeChat and delete their accounts in real time.

“When police raid the massage parlor, they ask ‘Who is the owner?’ My client will say, ‘Let me pull up my WeChat and show you,’ and there’s no such person,” Chung said.

Sometimes, all victims are left with is a first name or a nickname.

Amanda was working at Amazing Spa in Arizona when police raided the business in 2016. In an interview with officers in Mandarin, she said she learned about the job from a friend named Emily who gave her a person to contact on WeChat.

Amanda couldn’t remember the person’s screen name. Or the number she was told to call when she arrived in Phoenix. She could barely describe the man who picked her up from the airport – she said she never saw him again.

Shirley was told little by her new boss, except that someone would pick her up in Flushing, Queens, an enclave for newly arrived Chinese immigrants that has been identified by those who study sex trafficking as a common entry point.

She had no idea where she was headed when she got in the car. They drove for hours – to Virginia, she’d later learn. They finally stopped at a single-family house. There were two floors, with two bedrooms upstairs.

Shirley was told to stay in one of the rooms and be ready at 10 a.m., when the boss would start booking customers. He’d text when one was on the way. Sometimes another woman was there, too. But mostly Shirley was alone and scared to learn who would appear on the doorstep.

Two weeks later she was moved to Baltimore. She barely noticed a difference – the trappings were the same.

Illicit massage parlors are easy to spot. Their names include words Americans might associate with Asian culture like jade, oriental or jasmine, often in neon. Located in strip malls and shopping centers, their windows are blacked out or covered with stock images of serene customers, hot stones and lotus flowers. They stay open late and serve primarily men.

With minimal training, law enforcement, regulatory boards and community members can suss them out. And they have, stepping up raids and regulations over the past decade in efforts to combat trafficking.

Youngbee Dale, an anti-trafficking consultant who has trained law enforcement agencies and written peer-reviewed studies on the topic, said some of those efforts actually have driven the illicit business further underground.

In her research, Dale found evidence in Korean-American news reports that traffickers were moving operations to less obvious locations to avoid crackdowns.

“What we were seeing was a lot of young girls sold in storefront brothels or 12 to 20 women sold in one massage parlor,” Dale said. “We don’t see that anymore. One good reason is they want to evade anti-trafficking law enforcement.”

Residential brothels can be harder to identify, and they typically house fewer victims. A 2017 case in Washington began with a 911 call from a woman who said she was being forced to work as an escort and held against her will. She hung up after saying that the people forcing her to work had returned.

Police were dispatched to a Bellevue address. When they arrived, they found an Asian woman inside a sparsely furnished apartment with mattresses on the floor. Through a translation service, officers asked the woman, who went by Coco, if she was in danger. She said no.

Coco told police she had come to the U.S. from China a few months earlier, going through New York and on to Seattle. She said she had been staying in the apartment because her house was being renovated. When asked where her house was, Coco said she didn’t know. She told police her passport was with her boyfriend, whom she’d met through a friend.

“He is trying to get me a driver’s license so he held onto them,” she said, according to police reports.

When asked for her boyfriend’s phone number, police noted she appeared distressed.

“I don’t want you to bother him,” she said.

The case became part of a lengthy investigation into a cross-country criminal network that made hundreds of thousands of dollars from prostituting hundreds of Asian women.

Prosecutors argued that it was headed by a Chinese woman in her late 20s who lived in Queens but frequently traveled to Seattle. Fang Wang was accused of recruiting women for prostitution disguised as massage work and managing it all through WeChat.

In grand jury testimony, some women said they knew they’d be performing sexual services, others said they thought they’d be doing legitimate massage. Most were “in dire financial straits,” according to court records, owing money to people who helped get them into the U.S. and vulnerable because of their immigration status.

Five others also were charged. According to court records, they were drivers and couriers, who sometimes collected money from the women. Steven Thompson was a 60-year-old contract employee with Microsoft. He met Wang at a coffee shop and for years helped her rent apartments – a valuable asset, the prosecution argued, thanks to his native English.

Like Wang, most members of the organization were from China. Yaoan He, who rented the apartment where police found Coco, illegally overstayed his visa to the U.S. In his defense, he said he arrived in the U.S. in 2013 with his family while his wife was pregnant with their second child – a violation of China’s one-child policy. She had applied for asylum here.

Yunzhong Chen, another defendant, also had applied for asylum with his wife, citing China’s one-child policy. Zhoafeng Zhang, a college student from China, came to the U.S. to attend the University of Washington before he started working for the ring.

All pleaded guilty to either conspiracy to use a communication facility to promote prostitution or transporting individuals in furtherance of prostitution. Most charges were dropped in plea deals. Wang served the longest sentence: 2½ years.

In sentencing hearings, the judge said he was concerned by the seriousness of the crime and the lack of vigor with which it was pursued by the government.

Evidence in the case raised questions about whether Wang was a ringleader or just a cog in a much larger operation. In her defense, Wang said she had been recruited as a sex worker into Mexico and the U.S. by people who took advantage of her, according to court records.

“Ms. Wang insists that she acted at the direction of others, and was principally motivated by fear. She was subject to horrific sexual and physical abuse when she was first forced into prostitution. The threats and violence never stopped,” reads a memo submitted to the court by Wang’s attorney.

Zhang, who became an informant for the government after an arrest in 2015, said in his defense that he tried to tell investigators that the women worked for others in addition to Wang. He joined a WeChat group with 500 members, including ringleaders, brothel owners and more, he told the judge at his sentencing hearing.

“Those people were more culpable than Ms. Wang or other ringleaders, because they use more sophisticated means,” he said. “They try to deter law enforcement.”

The prostitution model Zhang described – with massive group chats and hundreds of victims recruited to work in houses and spas – are prevalent across the country.

As part of their investigation into Wang, federal and local law enforcement executed search warrants for more than 30 locations, almost all of them apartments or hotels. Investigators found thousands of ads with similar photos, descriptions and phone numbers using “massage” as code for sex. The phone numbers led to virtual “call centers” that data showed were as far away as New York and Washington, D.C., according to court records.

Residential brothels and outcalls have long been connected with illicit massage. So, too, are other forms of sex work.

In a 2016 case, State Department agents found Korean brothels in New York posing as legitimate spas but offering a special type of sexual service called the “girlfriend experience,” which can include outcalls, kissing and sex without condoms. Managers charged nearly double for the girlfriend experience.

Clients, largely Korean, were vetted and maintained on a list that agents said included 70,000 telephone numbers.

Experts say the mixing of multiple models of commercial sex suggests larger, more organized criminal rings – the way diversified corporations may have a variety of revenue streams.

“It’s similar to a portfolio – they have more flexibility built into the system,” Muller-Tabanera said. “If you close some businesses down, you just bring people back into the system doing dispatch and outcalls.”

He said his organization saw an increase in outcalls during the COVID-19 pandemic, when brick-and-mortar spas were closed or saw less business: “The ads still looked the same, but they were taking away addresses and replacing them with phone numbers of the dispatcher.”

Trafficking victims who provide services outside spas are not only harder to spot but also harder to help. Yet those locations can be more dangerous for the women working in them. At a spa storefront, there’s typically another worker – or more – in the same location; women working in hotels can be completely alone, at the mercy of customers.

“It’s a higher risk, and super-dangerous,” said Chung, with Garden of Hope. “I have heard really horrific stories from clients. They’ve been raped. … Customers saying ‘Just have sex with me or I’ll kill you.’ Really horrific stories.”

“Cherry” Ling Xu was in jail for trafficking-related charges in 2006 when she started talking about plans to kill the woman she suspected tipped off police. She told her cellmate she knew Cici – a former worker in one of Xu’s raided spas – had written the letter that got her busted.

Police had received an anonymous letter, titled “prostitution,” that said spa owners were “coercing, enticing, and exploiting Chinese women to reap a fortune for themselves, while sending the United States currency to mainland China,” according to court records.

Xu told her cellmate she could have Cici killed for $5,000, and she knew Cici’s family still lived in China.

The threat was one of many USA TODAY reporters found in illicit massage cases from the early 2000s. Reporters found fewer threats and less overt violence in recent cases – a trend advocates also have noted.

In the past, Chung said, clients told her they were hit if they didn’t provide sexual services.

“Now it’s just like: ‘Oh, don’t you have debt you need to pay off in China? If you don’t do this, how else are you going to pay it off? I’m sure you’re not going to find a job that will pay more.’ They use that kind of manipulation.”

In that way, traffickers create a false sense of trust or indebtedness with victims that can be akin to Stockholm syndrome – and minimize suspicion from law enforcement.

“We call it ‘big sistering,’” said Muller-Tabanera with The Network. “The boss, who is often female and who is at least one level up in the organization, is saying: ‘Hey, I helped you. You said you wanted to work, and I got you a job. We’re providing you a place to stay.’ It’s a different version of pimp control.”

L.L. arrived in Seattle three days before police found her in Diamond Spa, an unremarkable massage shop in the International District. She’d come from China, the same province as the spa’s owner, Lina Wang. She reached out to Wang before making the journey.

L.L. told police she stayed in a hotel her first night in the new city. But Wang told her that was too expensive and told L.L. she could crash in the spa instead.

She took Wang up on it. Once she got there, however, L.L. said she wasn’t allowed to leave. She lived inside the spa with two other women. Wang charged them $20 a day in rent, according to police reports.

L.L. said she had to perform massages to earn her keep, despite not having a license. She saw up to 12 customers a day. She told police the encounters weren’t sexual, though police had evidence to the contrary.

Traffickers isolate victims in spas as another form of coercion. Chung said most of her clients are recruited once they get to the U.S. They are taken outside their comfort zones, often to another state where they have no connections and no one outside their traffickers speaks their language. The women may be told they’re free to leave but have no way of actually getting back home.

In a 2017 case that saw three charged with trafficking persons for sexual servitude, women were recruited from Flushing and trafficked into Massachusetts by a 50-year-old Chinese woman who ran a handful of illicit spas. Some didn’t know they had been in another state, according to court transcripts.

Q: Do you know what city or town the workplace was in?

A: I did not know. I only knew this place is called Massachusetts. I didn’t ask.

Q: And do you know what city you were working in?

A: I did not know. Yeah, I only knew where to get off the bus from Flushing.

Q: And did you know what town or city you were in yesterday?

A: I did not know. I only know it’s in Massachusetts.

The woman accused of doing the recruiting, Fengling Liu, pleaded guilty to 15 charges including trafficking, money laundering and deriving proceeds from prostitution and was sentenced to five years in jail. As part of a plea deal, related charges against her husband and daughter were dropped.

Babi and CiCi also were working at the time of the raid at Amazing Spa in Arizona, the massage parlor where Amanda was enticed to work via WeChat.

Babi told police she wasn’t paid a salary, only tips. She slept in a little living area off the kitchen. When police asked if she was allowed to leave to get food or for personal reasons, she said yes, then admitted she’d never left.

CiCi gave similar answers. Their responses prompted a special notation in the police report:

“After interviewing [Babi] and [CiCi], I observed both had very similar answers to many of the questions. Despite both females being separated throughout questioning, it was noted by investigating detectives that answers provided appear to have been previously rehearsed or possibly instructed to both females. This theory has not been substantiated at this time, however was observed by several detectives investigating this case.”

In other cases reviewed by USA TODAY, victims also appeared to repeat stories their traffickers had told them, particularly about travel documents.

One of the victims in the Minnesota case in which 37 people were convicted or pleaded guilty said traffickers told her she didn’t need her passport because she had a California ID. But she didn’t get it back until she had paid off a $25,000 debt.

Another victim in that case was told customers might steal her passport. She later learned it was confiscated because the trafficker feared she’d run away, she testified in court.

Withholding passports or IDs has long been recognized as a red flag because victims can’t leave the country without them. Advocates say traffickers have increasingly relied on stories that prompt victims to turn over documents voluntarily, often under the guise of helping them.

As soon as Shirley arrived at the house in Virginia, the boss asked for her passport. He said it wasn’t safe with her and, if anything should happen – like a police raid – he’d handle it.

Chung said that’s typical of situations she sees with her clients.

“It doesn’t work anymore to say ‘Hey, I need your passport for you to have a job,’” Chung said. “They say it in a way that’s not threatening.”

In one case, Chung said a trafficker told her clients he would apply for visas for them – he just needed everyone’s passport.

Often the women “really do like these traffickers. They’re like, ‘He helped me,’” Chung said. “But if you go deeper, of course he’s not applying for a visa for them.”

Members of the Queens-based organization indicted in April were unusually brutal, according to unsealed court records.

Rong Rong Xu – also known as Eleanor – Bo Jiang, Siyang Chen, Meizhen Song and Jilong Yu had managerial roles in the organization, prosecutors say. Most started as enforcers before moving up the ranks and have legal residency in the U.S. In addition to scouting locations and managing money, they instructed the younger defendants how to punish women who they thought stepped out of line, according to court records.

Victims were mostly undocumented Chinese women working out of hotel rooms. They were bound and gagged with duct tape and zip ties. They were beaten with baseball bats, hammers and pipes. Their injuries sent some to the hospital and left others with loss of vision – and in wheelchairs.

In electronic chats found by investigators, defendants appeared to encourage more severe beatings if the first didn’t result in significant injuries.

“Beat (her) to death tomorrow. If she dares fight back, beat her more viciously. Get some results from the beating. Can’t waste the money,”Jiang said in a text, according to court records.

When victims heard about the attacks and became wary of Asian male customers, Yu recruited a “Mexican friend” to carry out the assaults, according to a memo by prosecutors arguing for permanent detention for the defendants.

Advocates and experts say that’s part of another alarming trend: customer violence as a means of control.

“Especially among Asian populations, we see direct physical violence (by traffickers) is much less common a tactic than in other populations,” said Kathy Lu, a staff attorney with Sanctuary for Families, which works with a service provider for survivors of gender-based violence in New York.

“We often see customer violence taking its place,” Lu said. “For example, if a victim is being particularly resistant, they might send in a customer who is known to be particularly violent to rape the victim.”

Lois M. Takahashi, director of the USC Price School in Sacramento, and John J. Chin, acting chair of the Department of Urban Policy and Planning at Hunter College of the City University of New York, had been working with HIV/AIDS outreach organizations with Asian and Pacific Islanders when they realized little was known about the massage workers who sought assistance.

With a grant from the National Institutes of Health, the academics led a team that interviewed more than 100 Chinese and Korean massage workers in New York and Los Angeles to inform policy initiatives.

Seventeen percent of the workers said they were coerced or forced to provide sexual services, but a larger proportion described abusive situations – often at the hands of customers.

Eighteen percent said a customer had physically hurt them in the past year, and 40% said a customer had forced them to have sex.

One study participant “described a client who choked her when she refused to provide extra services and another client who displayed a gun to force her to comply with his requests,” the study said. “One study participant saw one of her coworkers being raped while the management did nothing to intervene: ‘The boss, a 60-year old lady, saw it, shut the door, and left the massage parlor.’”

Muller-Tabanera, with The Network, said traffickers are smart enough to know they can use the violent atmosphere to their advantage by simply failing to stop it.

In a case in Washington called Operation Emerald Triangle, a spa worker told police officers she had been sexually assaulted by customers. In response, her boss told her to be accepting of both “good and bad customers.”

“She’s been assaulted on the job and the boss doesn’t care,” the police report said.

Tom Umporowicz, who ran Seattle Police Department’s Vice and High Risk Victims Unit at the time of the case, said he first learned about rampant rape and sexual abuse in spas through an offhand comment by a worker who came forward as an informant.

“She casually mentioned once, ‘Then something happened.’ It didn’t feel right, so I went to a female detective I knew and trusted and asked, ‘Can you debrief her and interview her more with an advocate to try to find out what this something else is?’” Umporowicz said. “Turns out she had been sexually assaulted four times in a year.”

She also told officers if an employee talked too much, or made one of the owners unhappy, the owner would have a guy beat them up.

Lu said employing customers to do their dirty work has been a way for traffickers to further distance themselves from the crime.

“It makes law enforcement more wary of prosecuting,” Lu said “when the facts are this complicated.”

During her short time in the industry, Shirley could see that her boss’s concern for maintaining business came at the expense of her safety. One client had been particularly rough.

“It felt like this person, how do I put this, like tearing your body apart?” she said. “That feeling is scary,”

When the man returned, she told the boss she didn’t want to provide services to him. “The boss said, ‘Why are you picking customers now?’”

She has worked with several service providers since then, translating documents and trying to help other women. Even if they manage to leave, Shirley said, the challenges of being an immigrant and former massage worker can be enough to drive women back, perpetuating the trafficking cycle.

“If our language skills don’t reach a certain level … we can only get jobs offered by other Chinese, and most of the time those jobs require relatively long working hours with low pay and not-so-ideal working environments like restaurants, nail salons and supermarkets. Moms face even more challenges like finding daycare,” she said.

“It’s all about money. That’s why many women choose to go back to illicit massage operations even though they once left and worked in other industries for a while. It’s really hard for them to live normal lives.”

Shirley wants to go back to school and become a writer. She’s working on a children’s book and wants to help more women who find themselves in her position. Earlier this month she spoke at a national anti-trafficking convention.

“A lot of people showed up at my session and discussed ways of ending human trafficking. And a lot of people hugged me,” she said. “Seeing so many people and organizations supporting us makes me feel hopeful about the future.”

Contributing: Kevin Crowe, Josh Meyer, Maria Perez, Anne Ryman, Chris Quintana.