Yves here. Most Western governments like to pretend that that they are not in the business of industrial policy. In fact, they clearly are, in the form of numerous subsidies, like interest rate breaks, tax credits, subsidies, borrowing guarantees and large and lax government purchasing schemes. So in the US, the preferred sectors include the medical care,1 real estate, higher education, and arms makers.

So then the question becomes, if governments were to get past neoliberal/libertarian and decide to engage in overt industrial policy, how does one go about it? There’s a solid case that tariffs are not a great tool. This look at how the Chinese boosted their shipbuilding industry via investment and production subsidies, which did indeed generate a big gain in global markets share. The post then looks at whether there was a welfare benefit in China.

By Panle Barwick, The Todd E. and Elizabeth H. Warnock Distinguished Chair Professor, University of Wisconsin – Madison; Myrto Kalouptsidi, Professor of Economics, Harvard University; and Nahim Bin Zahur. Originally published at VoxEU

Industrial policy has been used by many countries throughout history. Yet, it remains one of the most contentious issues among policymakers and economists. This column outlines a theory-based empirical methodology that relies on estimating an industry equilibrium model to measure hidden subsidies, assess their welfare consequences for the domestic and global economy, and evaluate the effectiveness of different policy designs. It applies the methodology on China’s recent policies to promote its shipbuilding industry to dissect the impact of such programmes, what made them (un)successful, and to explain why governments have chosen shipbuilding as a target.

Industrial policy refers to a government agenda to shape industry structure by promoting certain industries or sectors. Although casual observation suggests that industrial policy can boost sectoral growth, researchers and policymakers have not yet mastered predicting or evaluating the efficacy of different types of government interventions, nor how to measure the overall short-run and long-run welfare effects (Juhasz et al. 2023, Millot and Rawdanowicz 2024). In this column, we focus on one particular example of industrial policy: the shipbuilding sector.

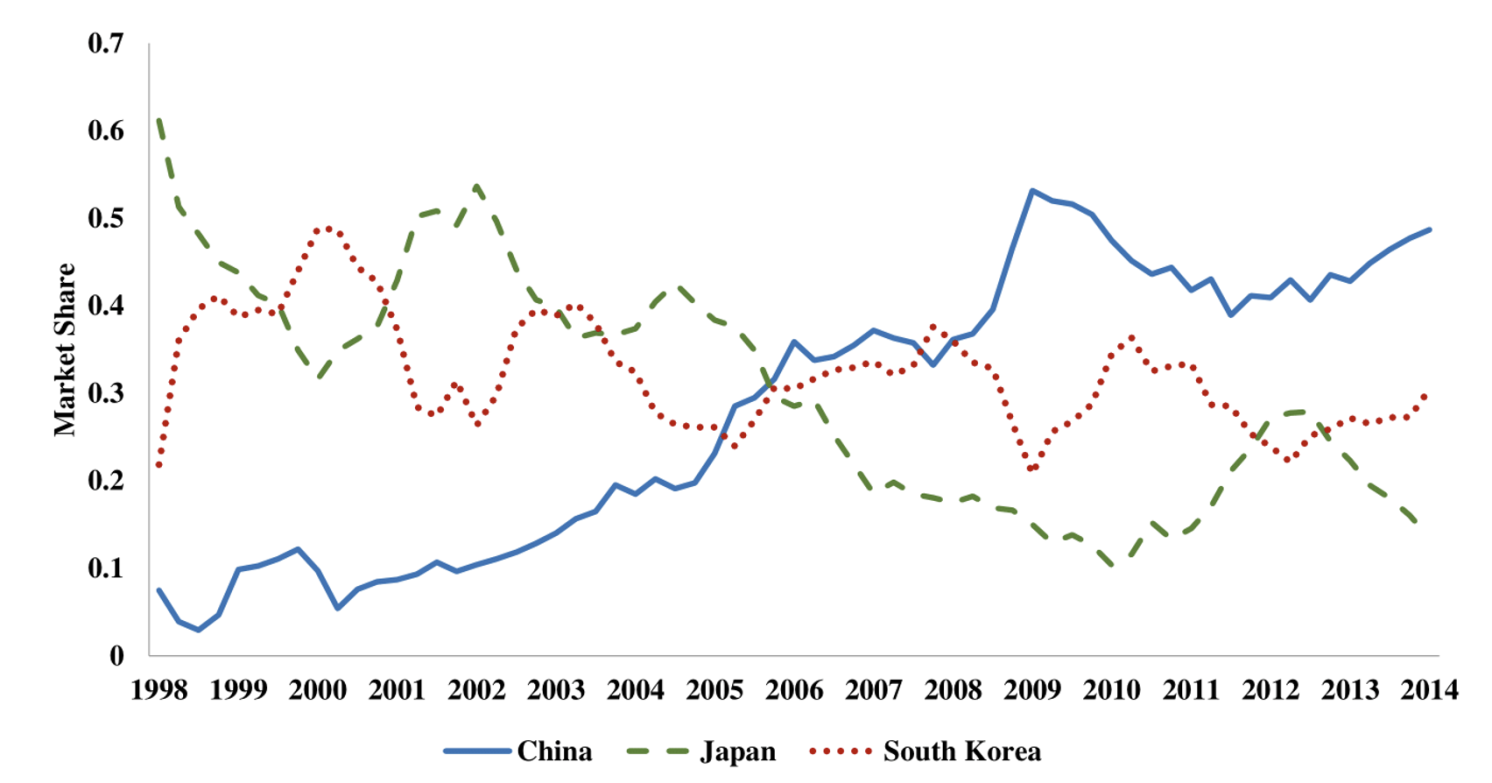

The history of shipbuilding is as tumultuous as the seas themselves. Shipbuilding has always held an allure for governments, in its real and perceived interactions with industrialisation, maritime trade, and military strength (Stopford 2009). Figure 1 shows the succession of countries as the world’s dominant shipbuilding nation. The UK held the lion’s shareof the industry for the better part of the 19th and 20th centuries, fending off competition from other Western European economies (mainly Germany and Scandinavia) at times. After WWII, it is swiftly overtaken by Japan, which prevails as aworld leader until the 1980s, when South Korea dominates the global market.

Figure 1 Share of commercial ships produced by each country, 1892-2014

Note: This figure plots the world market share in terms of the number of ships delivered from 1892-2014 for the major ship producing countries.

Source: Data for 1892-1997 was obtained from historical issues of the World Fleet Statistics published by Lloyd’s Register, while the data from 1998 onwards is based on Clarksons data. We group together all European shipbuildingcountries except for the UK under ‘Europe’.

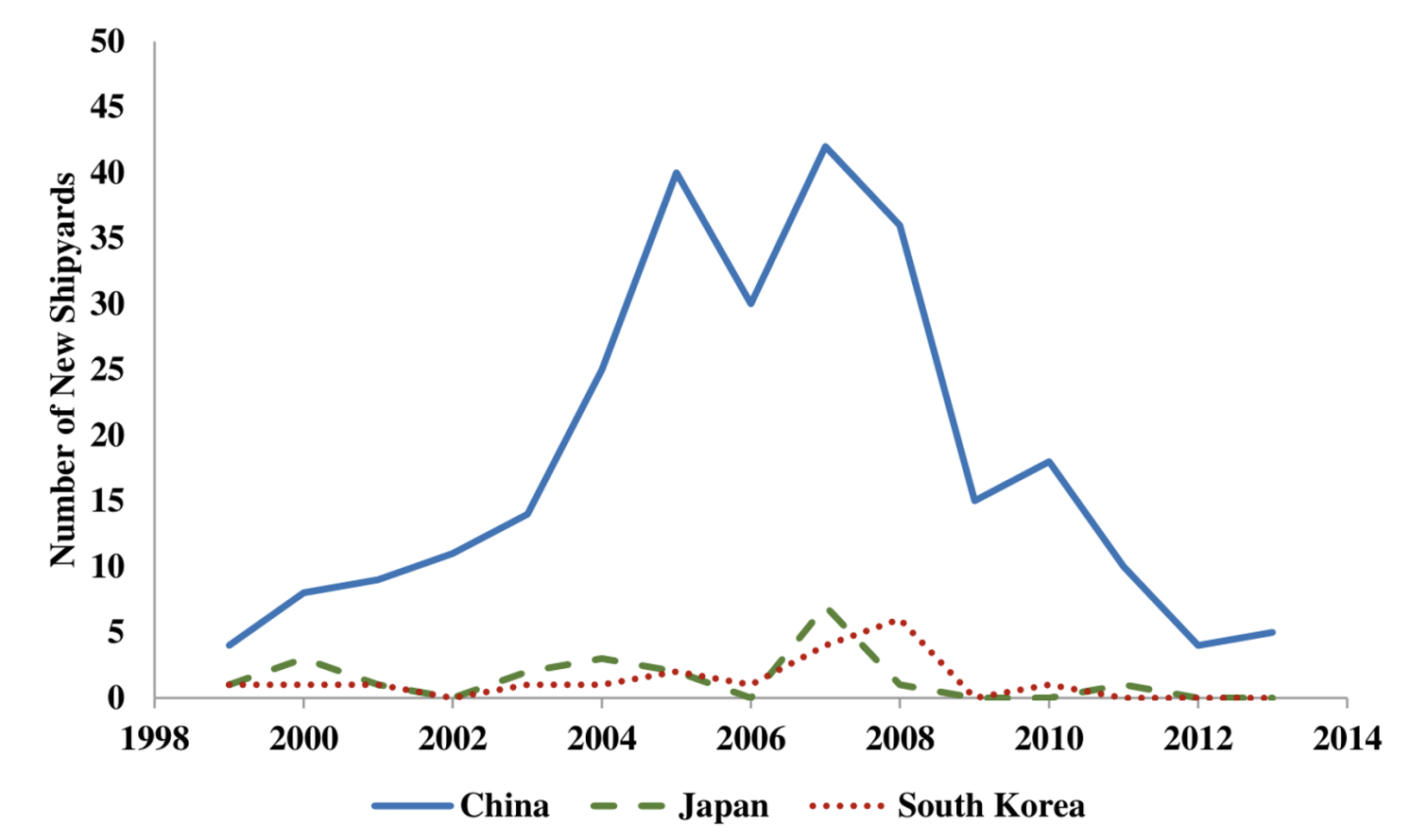

In the 2000s, China entered the shipbuilding scene. In 2002, former Premier Zhu inspected the China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC), one of the two largest shipbuilding conglomerates in China, and pointed out that “China hopes to become the world’s largest shipbuilding country (in terms of output) […] by 2015.” Within a few years, China overtook Japan and South Korea to become the world’s leading ship producer in terms of output. Figure 2, PanelA shows the rise in China’s global market share of shipbuilding by plotting China’s total shipbuilding output as a share of global output. China’s national and local governments provided numerous subsidies for shipbuilding, which we classify into three groups. First, below-market-rate land prices along the coastal regions, in combination with simplified licensing procedures, acted as ‘entry subsidies’ that incentivised the creation of new shipyards. As shown in Panel B of Figure 2, between 2006 and 2008, the annual construction of new shipyards in China exceeded 30 new shipyards per year; in comparison, during the same time period, Japan and South Korea averaged only about one new shipyard per year each.

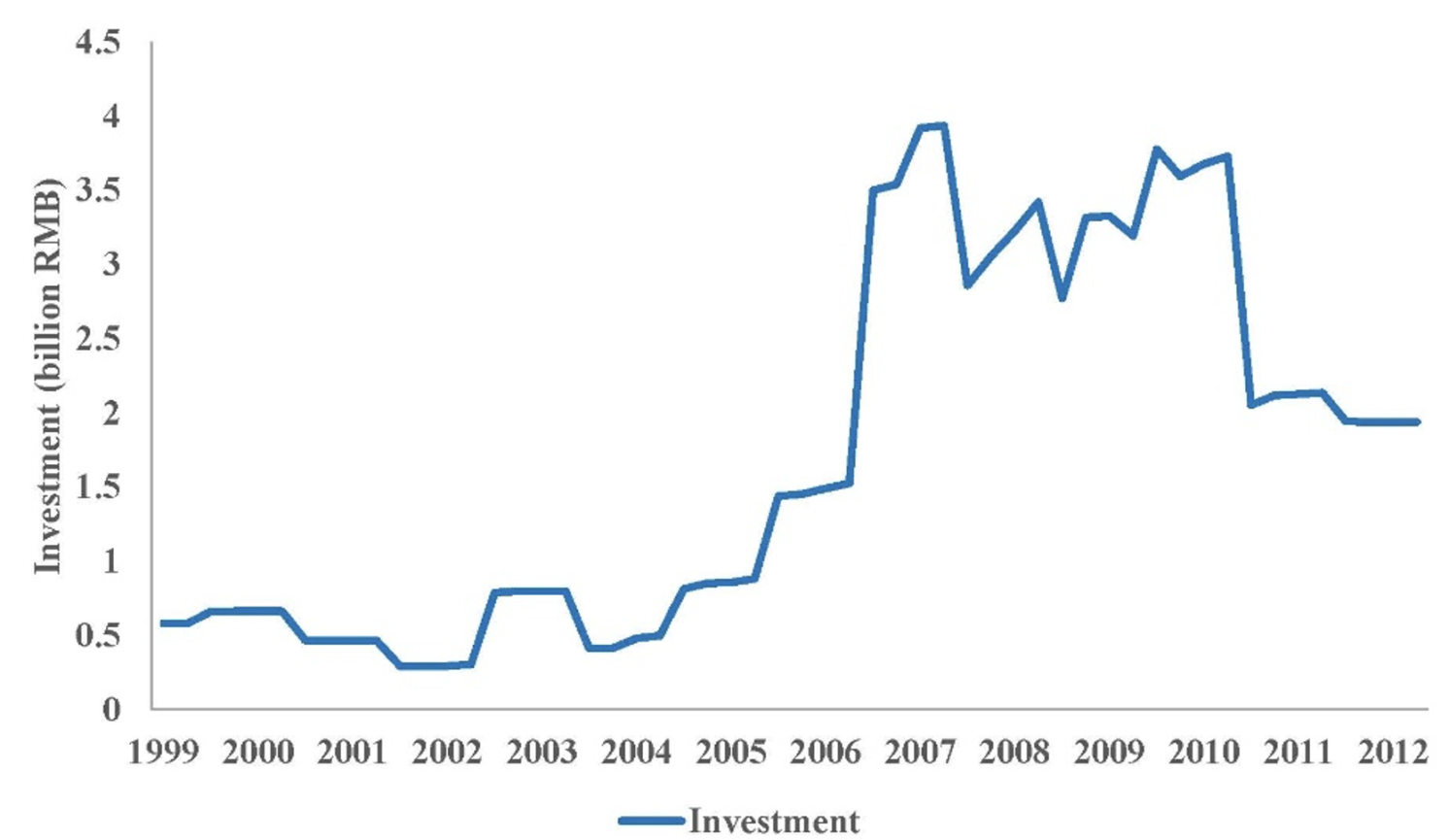

Second, regional governments set up dedicated banks to provide shipyards with ‘investment subsidies’ in the form offavourable financing, including low-interest long-term loans (a common industrial policy tool, as illustrated also by the programmes in Japan and South Korea) and preferential tax policies. China’s rise in total capital invested in shipyards is illustrated in Panel C of Figure 2. Third, China’s government also employed ‘production subsidies’ of various forms, such as subsidised material inputs, export credits, and buyer financing. The government-buttressed domestic steel industryprovided cheap steel, which is an important input for shipbuilding. Export credits and buyer financing by government-directed banks made the new and unfamiliar Chinese shipyards more attractive to global buyers.

Figure 2 The rapid expansion of China’s shipbuilding industry

A) Market share

B) Number of new shipyards

C) Investment

Notes: Market shares by country are computed from quarterly ship orders. Number of new shipyards is computed annually and by country. Industry aggregate quarterly investment by Chinese shipyards in billions of 2000 yuan.

Source: Barwick et al. (2024), using data from Clarksons Research and China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

The combination of these policies was followed by a sharp expansion in China’s shipbuilding production, market share, and capital accumulation. China’s market share grew from 14% in 2003 to 53% by 2009, while Japan shrunk from 32% to 10% and South Korea from 42% to 32%. Then came the Great Recession of 2008-09, which drove the global shipping industry to a historic bust. The large number of new Chinese shipyards exacerbated low capacity utilisation and contributed to plummeting global ship prices. The effectiveness of China’s industrial policy was questioned. In response to the crisis and in an effort to promote industry consolidation, the government unveiled the “2009 Plan on Adjusting and Revitalizing the Shipbuilding Industry” that resulted in an immediate moratorium on entry and subsequently shifted support towards only selected firms in an issued ‘whitelist’.

Kalouptsidi (2018) and Barwick et al. (2024) study the impact of China’s 21st century shipbuilding programme on industry evolution and global welfare. To our knowledge, this work is the first attempt at evaluating quantitatively industrial policy in shipbuilding globally and among the first papers employing the structural industrial organisation methodology to understand the welfare implications and effective design of industrial policy more generally.

We build a model that is flexible enough to capture rich dynamic features of a global market for ships. On the demand side, a large number of shipowners across the world decide whether to buy new vessels. Their willingness-to-pay for new ships depends on present and expected future market conditions, notably on world trade and the current fleet level. On the supply side, shipyards located in China, Japan, and South Korea (which account for 90% of world production) decide how many ships to produce, by comparing the market price of a ship and its production costs. In addition, shipyards decide whether to enter by comparing their lifetime expected profitability to entry costs, which include the costs to set up a new firm (such as the cost of land acquisition, shipyard construction, and any initial capital investments) and the implicit cost of obtaining regulatory permits. They exit if expected profitability from remaining in the industry falls below a given threshold, capturing the shipyard’s ‘scrap’ value (that is, the proceeds from liquidating the business, as well as any option values of the firm). Firms also invest to expand future production capacities. For estimation, we employ a rich dataset consisting of firm-level quarterly ship production between 1998 and 2014, firm-level investment, entry andexit, and new ship market prices by ship type (containerships, tankers, and dry bulk carriers, which together account for 90% of global sales).

Our estimates suggest that China provided $23 billion in production subsidies between 2006 and 2013. This finding is driven by the cost function obtained from this analysis, which exhibits a significant drop for Chinese producers equal to about 13-20% of the cost per ship. Simply put, Chinese shipbuilding firms were ‘over’-producing after 2006 compared to our prediction of output without subsidies. Altogether, China provided $91 billion in subsidies along all three margins – production, entry, and investment – between 2006 and 2013. Notably, entry subsidies were 69% of total subsidies, while production subsidies were 25%, and investment subsidies accounted for the remaining 6%. These estimates reflect the fact that shipbuilding firms ‘over-entered’ (recall the astonishing entry rates during the boom years of 2006-2008) and ‘over-invested’ (recall the striking increase in investment during the bust), as shown earlier in Figure 2.

Our structural model suggests that China’s industrial policy in support of shipbuilding boosted China’s domestic investment in shipbuilding by 140%, and more than doubled the entry rate. It also depressed exit. Overall, industrial policy raised China’s world market share in shipbuilding by more than 40%.

Calculating whether this increase in sectoral output should be counted as an increase in welfare is a more delicate question. First, 70% of China’s output expansion occurred via stealing business from rival countries. There is evidence (backed by our cost estimates) that Chinese shipyards are less efficient than their Japanese and South Korean counterparts; thus, the transfer of shipbuilding to China constitutes a misallocation of global resources. Second, China’s industrial policy for shipbuilding led to considerable declines in ship prices. Lower ship prices benefited world ship-buyers somewhat, though only a modest amount accrues to Chinese ship-buyers, as they accounted for a small fraction of the world fleet. Third, and most importantly, although China’s shipbuilding subsidies were highly effective at achieving outputgrowth and market share expansion, we find that they were largely unsuccessful in terms of (domestic) welfare measures. Theprogramme generated modest gains in domestic producers’ profit and domestic consumer surplus. In the long run, thegross return rate of the adopted policy mix, as measured by the increase in lifetime profits of domestic firms divided by totalsubsidies, is only 18%, meaning that for every $1 the government spends, it gets back 18 cents in profitability. In other words, the net return when incorporating the cost to the government was a negative 82%, with entry subsidies explaining a lion’s share of the negative return.

Entry subsidies are wasteful – even by the revenue metric – and lead to increased industry fragmentation and idleness. Entry subsidies attract small and inefficient firms. In contrast, production and investment subsidies increase the backlog and capital stock, which lead to economies of scale and drive down both current and future production costs. As such, they favour large and efficient firms. Indeed, the take-up rate for production and investment subsidies is much higher among efficient firms: 82% of production subsidies and 68% of investment subsidies is allocated to firms that are more efficient than the median firm, whereas only 49% of entry subsidies goes to more efficient firms.

In terms of policy design, a counter-cyclical policy would outperform the pro-cyclical policy that was adopted by a large margin: strikingly, subsidising firms in production and investment during the boom leads to a gross rate of return of only 38% (a net return of -62%), whereas subsidising firms during the downturn leads to a much higher gross return of 70% (a net return of -30%). Moreover, if an ‘optimal whitelist’ is formed – that is, the most productive firms are chosen for subsidies – the gross rate of return would climb to 71%.

Our results highlight why industrial policies have worked better for some countries. In East Asian countries where industrial policy was often considered successful, the policy support was often conditioned on firm performance. In contrast, in Latin America where industrial policies often aimed at import-substitution, no mechanisms existed to weed out non-performing beneficiaries (Rodrik 2009). In China’s modern-day industrial policy in the shipbuilding industry, the policy’s return was low in earlier years when output expansion was primarily fuelled by the entry of inefficient firms but increased over time as the government relied on ‘performance-based’ criteria via its whitelist. Such targeted industrial policy design can be substantially more successful than open-ended policies that benefit all firms.

In terms of the rationale – why China subsidised shipbuilding – the standard arguments for industrial policy do not seem to apply especially well in our setting. The shipbuilding industry is fragmented globally, market power is limited, and markups are slim. Thus, there are no ‘rents on the table’ that, when shifted from foreign to domestic firms, outweigh the cost of subsidies. We find little evidence of learning-by-doing, perhaps because the production technology for the ship types that China expanded the most, such as bulk ships, was already mature. Spillovers to other domestic sectors are limited; in addition, more than 80% of ships produced in China are exported, which limits the fraction of subsidy benefits that is captured domestically. A scenario whereby Chinese output growth forces competitors to exit does not seem first-order either: by 2023, no substantial foreign exit occurred.

Our analyses point to two alternative potential rationales. First, as China became the world’s biggest exporter and a close second largest importer during our sample period, transport cost reductions from increased shipbuilding and reduced shipping costs can lead to substantial increases in its trade volume. Our estimates suggest that China’s industrial policy expanded the global shipping fleet, reduced freight rate, and raised China’s annual trade volume by 5% ($144 billion) between 2006 and 2013. This increase in trade was large relative to the size of the subsidies (which averaged $11.3 billion annually between 2006 and 2013). Of course, ‘more trade’ does not translate directly into economic well-being, but the relative magnitudes are suggestive. Second, both military and commercial deliveries at shipyards that produce military ships experienced a multi-fold increase, although military production appeared to have accelerated after the financial crisis and continued to increase throughout the sample period, providing suggestive evidence that China’s supportive policy might have benefited its military production as well.

See original post for references

_____

1 Not just big R&D subsidies but also the huge tax break of employer-paid health insurance being a tax deduction to the company but not taxable income to the recipient, like most other employer-provided benefits.