The Financial Times has a long article, even by “Big Read” standards, on the fact that investors are finally starting to fret about the looming financial downside of bad climate outcomes. But those of you who read Lex in depth: how investors are underpricing climate risks in full will be troubled by the lack of imagination about how bad the downside could be. Albeit the stakes are vastly higher, but it’s as if you were transported back by time machine to 2007 when it started to come out that rating agencies has not allowed for the possibility of a nation-wide decline in housing prices in their models for subprime debt.

Now admittedly this is progress of sorts since the 2006-2007 IPCC reports. In 2006, at the instigation of the UK Treasury, Sir Nicholas Stern published the so-called Stern Review, which sought to estimate the economic costs of climate change. To make a very long story short, Stern had to use what many regarded as unrealistically low discount rates (0.5%) to make seriously bad climate impacts, generally seen then as not occurring until after 2100, to be worth bothering about now.1

This conclusion reflects several fallacies: the first that climate change downside should not be put in an investment framework but an insurance framework. With any sort of properly-priced insurance, the average buyer pays way more than the expected value of the bad event happening to them. That is because the price of catastrophic outcomes is very high, at least life-changing if not life destroying.

Even though AOC has fallen out of favor, the argument she makes that health care should not be a market good should apply to preserving the environment from disaster.

”How much will you pay to live? Because the answer is everything; you will do anything to live. And that’s what makes the price of medicine different from the price of an iPhone.”

AOC on the commodification of health care. pic.twitter.com/WY3nubBO7m

— Arkansas Worker (@ArkansasWorker) January 24, 2020

To draw the analogy further, US military experts were already warning the Pentagon in the early 2000s (as in before the Stern Report) of greatly increased international instability due to climate change, both to mass migration as cities and mega-cities in low-lying areas are made uninhabitable by storms and sea level rises (Bangladesh for starters) and greatly intensified competition for resources, particularly potable water. We got a taste of how suddenly things could go chaotic with the Arab Spring revolts, triggered by price increases in food and cooking fuel. Those were merely domestic upheavals. What happens with far more acute stresses and far bigger numbers of desperate people, who as AOC notes merely in price terms for health care, will do anything to survive?

But the path towards bad outcomes is incremental, over decades if not centuries, with innumerable decisions and actions all paying into the degradation….all taking place in a market system which doesn’t price in those costs. So in effect, we all get paid via wages higher and prices lower than they would otherwise be to destroy the planet.

The second fallacy is the failure to consider tight coupling, as in events or shocks will propagate across a system too quickly for them to be interrupted. That does not even mean that they have to happen quickly in real time, just too quickly for the cascade to be interruputed. Many of the systems of the modern world are tightly coupled, such as many electrical grids (particularly ones in America) and supplies of critical goods (recall how the Puerto Rico hurricane led to a protracted shortage of IV bags because a factory there was the dominant producer). In an odd way, the US/NATO conflict with Russia and US escalation with China is accidentally forcing some industries to get ahead of the problem but leading them to somewhat deglobalize and focus more on less risky regional supply chains. But what happens when regular floods and sea level rises imperil sewage treatment plants in the coastal area of the US? Imagine the cascade of events if that (more like when) that becomes a widespread issue.

The third fallacy at work is that tails are fat. Tail events are far more likely and more extreme that people who live in Mediocristan believe. And those risks are higher in systems with a lack of safety buffers. For instance, Jared Diamond and others have argued that the Mayan civilization was ecologically precarious, and successive droughts led to famine. How many years of widespread food shortages could most societies take?

Now to the Financial Times story. Now that very bad environmental outcomes could start appearing in the 2040 to 2050 timeframe, as oppose to the “Oh, what, me worry?’ after 2100 scenarios, some investors are taking notice. Mind you, this story is intended to be extremely sobering, but as indicated above, I suspect many will find it to be weak tea. Some key snippets:

The big danger is of a “climate Minsky moment”, the term for a sudden correction in asset values as investors simultaneously realise those values are unsustainable.

So far, businesses and investors have paid less attention to the physical effects of climate change….

The article then describes how the Singapore sovereign wealth fund engaged Cambridge Econometrics and Ortec Finance to perform an analysis. The big findings:

The net zero forecast results in cumulative returns over 40 years at 10% lower than baseline. The “failed transition” projection of temperatures 4C higher than pre-industrial levels by 2100 finds returns are 40% lower than baseline.

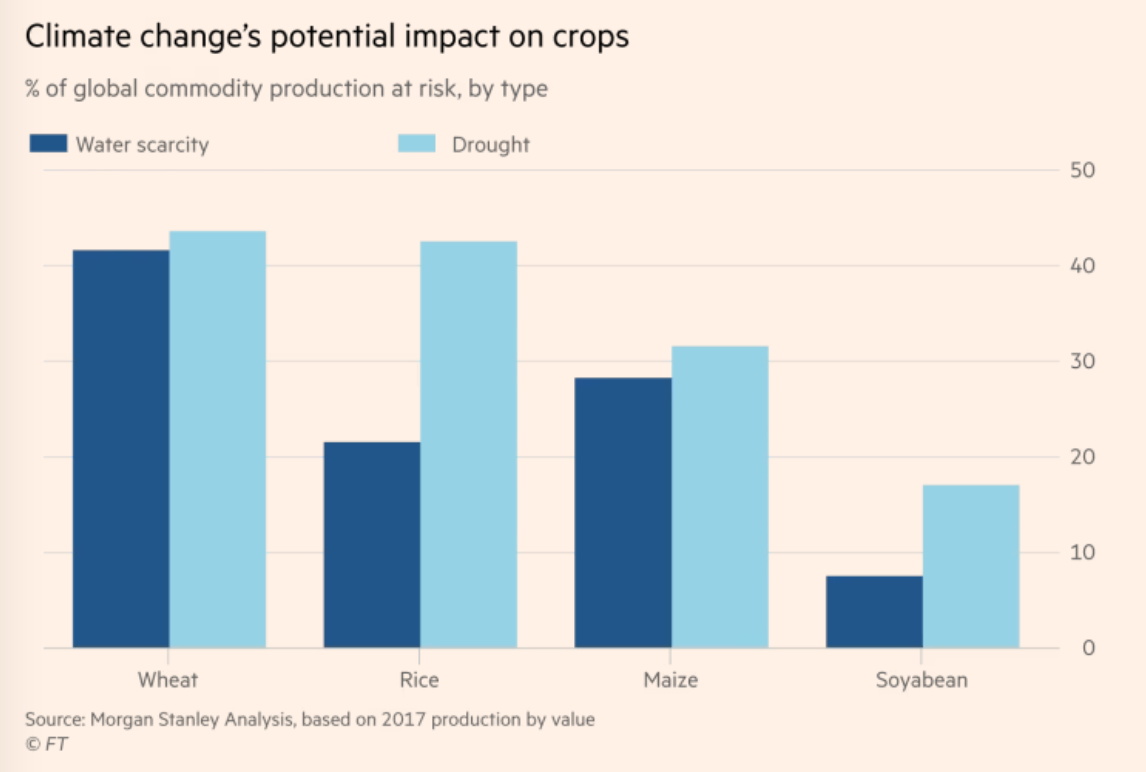

The analysis flags food output as a major source of risk. I am surprised that it does not give pride of place to the resource set to come under acute pressure first, potable water (you’ll see how it address that shortly). Nevertheless:

It is doubtful that this study considered the knock-on effects of scarcity, which is that producing countries start hoarding so as to have buffers to prevent distress at home in case their output flucuates. In addition, it contains other simplistic cheery ideas, like as global warming progresses, farther north areas will have longer growing seasons than now, so crop production can shift northward (from a northern hemisphere persepctive).

While that likely will happen, the problem is that on average these areas will be less productive. Sunlight is weaker in farther north and south latitudes. The same factors that make these regions not so good for solar energy also makes them less productive for photosynthesis.

Next the article turns to water:

Agriculture accounts for about 70 per cent of freshwater consumption globally, although in regions such as Asia it can be higher. Already 2bn people(opens a new window) lack access to clean, safe drinking water. By 2030, demand for freshwater is forecast to exceed supply by 40 per cent(opens a new window).

There again is more here than meets the eye. Most of the solutions to water shortages involve energy use, such as desalination or other water purification means. So solving the water problem will work against the “reduce energy use” imperative. And the problems are already becoming acute. In Panama, there may not enough freah water to keep the Panama Canal levels high enough for regular ship passage and supply local farmers. I had seen articles suggesting Panama desalinate water for use by farmers, but other stories depict that as unrealisti. From Agence-France Press, Drought-hit Panama Canal must ‘adapt or die’ as water levels drop, in early August:

The canal relies on rainwater to move ships through a series of locks that function like water elevators, raising the vessels up and over the continent between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

However, a water shortage due to low rainfall has forced operators to restrict the number of vessels passing through, which is likely to result in a $200 million drop in earnings in 2024 compared to this year, canal administrator Ricaurte Vasquez said…

If the drought and resulting restrictions continue, Vasquez fears shipping companies will “opt for other routes.”

This includes the Strait of Magellan — a natural passage at the tip of South America between the mainland and the Tierra del Fuego archipelago…

The lack of rain has also increased the salinity of the lakes and rivers that make up the canal’s watershed — which also provides water to three cities, including the capital Panama City.

“Every time we open the gate that leads to the sea, seawater is mixed with fresh water,” said Vasquez…

“We have to keep that level of salt water within a certain range, because the water treatment plants do not have desalination capacity,” he added.

The dwindling freshwater cannot be replaced with sea water — as used by the Suez Canal which connects the Mediterranean with the Red Sea — as this would require massive excavations.

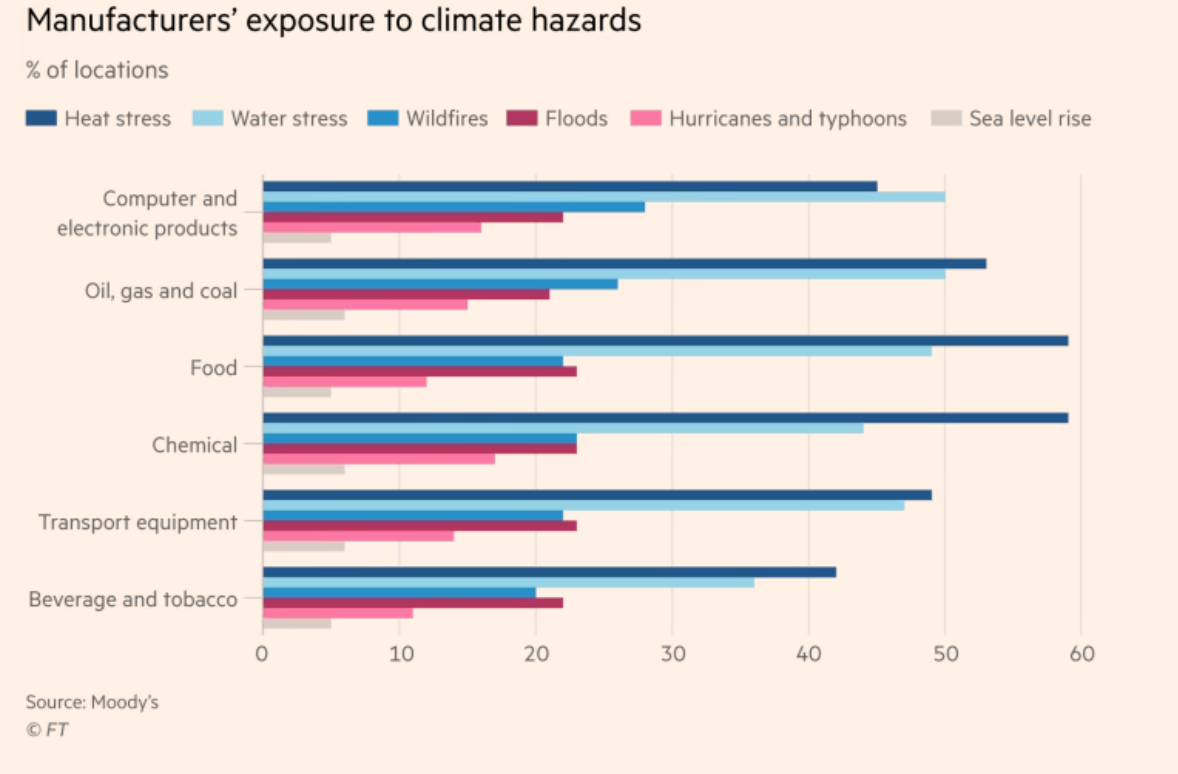

The analysis then considers flood risk…but oddly the impact only on manufacturing, not flooding of major cities and mass migration:

In fairness, the Financial Times story proper does think to include displacement, but in a bizarrely unimaginative manner:

Globally, the movement of people away from hard-hit areas is likely to be on a far bigger scale. More than 20mn people a year on average have been displaced by extreme weather-related events since 2008. By 2050, as many as 1.2bn could be uprooted by climate change, according to the Institute for Economics and Peace think-tank.

Florida will be first to go:2

The article discusses mitigations, ranging from the aforementioned desalination, dykes and improved crop science to how the holiday industry could adapt.

And at the very end of this very long piece, the pink paper does inject a suitably sober note. One might wonder why the bit we boldfaced was not mentioned earlier on:

Yet many models also omit factors that could make the outcomes far worse than predicted. Many assume that climate change does not slow gross domestic product growth. They do not take account of mass migration. Climate tipping points, such as thawing permafrost or an ocean circulation collapse, are rarely included.

More fundamentally, the past is an unreliable guide to the future. Modellers typically use a quadratic function to plot the relationship between damages and temperatures. Some 2 per cent of output would be lost at 3C of warming, while 8 per cent of output would be lost at 6C of warming, according to Nordhaus’s 2016 model. There is great uncertainty about the potential effects of such large rises, but even so the credibility of those predictions looks weak.

It makes more sense to conduct a reverse stress test, argues a new report(opens a new window) from the UK’s Institute and Faculty of Actuaries. This involves working backwards from an as-yet undefined temperature at which the world’s economy would plausibly cease to function. Using this logic, the report’s authors suggest that half the world’s GDP could be destroyed as early as 2070.

There is a cavernous gap between such cataclysmic forecasts and the modest impacts anticipated by pension funds and listed companies in their climate risk reporting….

There is growing unease that existing climate models may be providing a false sense of security.

Gee, ya think? This closing bit epitomizes the official response to climate change: too little, too late.

____

1 This is no surprise to anyone who has done financial modeling. Unless interest rates are super low, anything that happens more than 15 years out is worht pretty much zero once you discount it back to the present.

2 Lyrics to Jay Leonhardt’s Goodbye Miami:

Carbon monoxide is spewing from cars

It blots out the sun, it blots out the stars

Heating the atmosphere scientists say

Melting the icecaps away.

As the ice melts, it is not surprising

The oceans are ever so steadily rising

Steadily rising through high tide and low

Florida will be first to go.Goodbye Miami, goodbye Lauderdale

Pass me a bucket, pass me a pail

Old folks and condos are up to their knees

With the wind and the salt and the sea.Goodbye Miami, goodbye Sarasota, the

Gulf Coast now reaches Pierre, North Dakota

Tampa is dampa than ever before

And Key West ain’t Key West no more.They’ll be no need to worry about air pollution

When you’re up to your neck in a saline solution.

The tide she comes in and she lingers about, but the tide

She don’t want to go out.