By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

Readers may have noticed that I link to Myanmar news a good deal, perhaps more than its geopolitical importance warrants. However, I am more interested in Myanmar’s internal struggles: The current civil war is a natural experiment in whether an armed resistance against an extremely brutal and stupid military junta can succeed on its own, without — and this is the key point — any color revolution nonsense exported from the United States. So I imagine there are many, repressors and insurgents alike, who are following Myanmar with interest.

Recent headlines suggest that the Myanmar’s civil war may be reaching its culminating point for Myanmar’s military, the Tatmadaw[1]:

Junta moves to ‘fortify Naypyitaw at all costs’ Myanmar Now. (Naypyitaw is the monstrous capital, in the center of the country, founded by the military in 2005.)

Revolution and the Escalating Collapse of Myanmar’s Junta The Irrawaddy

Shan State Omen: Is Myanmar’s Junta Losing Control of the War? The Diplomat

Armed Rebels Seize Nearly 50% Of Myanmar In Military Offensive; Junta Says Nation On The Brink Of Breaking Apart Eurasian Times

Commentary: The Myanmar military is losing control Channel News Asia

‘A real blow for the junta’: Myanmar’s ethnic groups launch unprecedented armed resistance France24

Myanmar’s NUG negotiates ethnic differences as crisis deepens Al Jazeera

Is the rule of Myanmar’s junta under threat? Reuters

Let’s begin with a map:

As you can see, Myanmar is bordered by Bangladesh, India, China, Laos, Thailand, and the Andaman Sea (the United States being a maritime power). Myanmar has two rivers, its own Irrawaddy and the Mekong, which China cares about as a means of controlling its downstream “neighbors.” The map does not show that China has built a pipeline across Myanmar as part of its Belt and Road Initiative. Some say these factors make Myanmar of central importance to China (and therefore to India (and possibly to the United States)) but personally, I don’t think that (going East) “Gateway to Yunnan” or (going West) “Gateway to the Bay of Bengal” are especially compelling.[2]

The key feature of the map is the names of the various “states” or provinces: Kachin, Shan, Chin, Mon, Kayin, and so forth. These indicate not only political entities, but ethnicities, a key point in understanding Myanmar’s politics (which I will forthrightly admit I do not. In all, there are more than 135 ethnic groups in Myanmar’s 55 million population).

Therefore, geopolitics are out of scope for this post (including ASEAN). So is Myamar’s tortured and tragic political history (here is a timeline), although I may allude to key events as I go along. Rather, I will focus on the key players in the Myanmar civil war: The Tatmadaw, the National Unity Government (NUG), the NGOs (who are much the same in Myanmar as they are anywhere), the locals, and the Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs)/People’s Defence Force (PDFs). This is, in other words, not a binary story of fascist regime[3] vs. democratic resistance. There are a lot of players! Let us take each in turn.

Tatmadaw

Myanmar’s military government is stupid. From George Packer in 2008:

Four days after [Cyclone Nargis] made landfall, with whole districts of lower Burma under water, tens of thousands of people dead, and a growing danger of mass disease and starvation, government officials announced that the situation was returning to normal and that voting on a proposed constitution would take place on May 10th as scheduled in most districts.

(Yes, they handle the economy just as as well.) The Cyclone Nargis debacle led directly to the 8888 uprising, the rise of Nobelist and NGO-beloved Aung San Suu Kyi, and a military coup even more brutal than the military government that precded it.

Myanmar’s military is also brutal. Their fundamental strategy against their civilian population is described by Sophie Ryan, in “When Women Become the War Zone: the Use of Sexual Violence in Myanmar’s Military Operations“:

The Myanmar military is infamous for its brutal ‘Four Cuts’ doctrine. The literature available on this strategy, and its implementation through a corollary, though lesser-known, area colour-classification strategy, frames sexual violence as a permissible tactic within the strategies for achieving civilian relocation and intimidation. The Four Cuts strategy is a doctrine aimed at countering guerrilla movements by delivering four ‘cuts’ to insurgents’ food supply, funds, intelligence, and possible recruits. In Maoist terms, the supporting ‘water’ is taken away from the ‘fish’…. Operationally, it is implemented through ‘clearing operations’ and ‘scorched earth’ policies. Such assaults have been documented as usually four-fold in character: first, an initial ‘assault’ drives out insurgents and civilians in the area; second, the area is ‘cleared’ by destruction; third, information is ‘gleaned’ from insurgents and inhabitants; and fourth, the area is made uninhabitable by ‘mining’ it with landmines. Smith notes that the effect is that ‘[f ]or the Tatmadaw in the Four Cuts campaign there is no such thing as an innocent or neutral villager. Every community must fight, flee or join the Tatmadaw’. These offensives are often facilitated by a three-stage colour classification system whereby areas are designated as black, brown or white according to the perceived degree of insurgent control over the area… Former soldiers have described being told in black areas to ‘do whatever you want’ to civilians, including rape.

The Four Cuts strategy is still used by the Tatmadaw in today‘s civil war. Hence the pictures and satellite maps of burning villages, etc.

However, due to EAOs/PDFs (see below) combining, the Tatmadaw may be reaching their culminating point, unable to perform their operations (the Four Cuts being the essential one). From War on the Rocks, “The Myanmar Military Is Facing Death by a Thousand Cuts“:

Events in Myanmar’s renewed civil war took a dramatic turn these past three weeks, reminding us not to forget about the world’s longest running conflict. Just prior to the break of dawn on Oct. 27, 2023, the Three Brotherhood Alliance of the Arakan Army, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army launched a surprise assault — called Operation 1027 — on junta forces in northern Shan State. Within a couple of weeks, the three ethnic armed organizations have reportedly seized over 150 military outposts and several key towns astride a strategic road to the Chinese border, as well as highways crisscrossing Shan State.

…While the fog of war demands analytical caution, Operation 1027 carries important implications for the future of Myanmar. First, the Myanmar military is increasingly overstretched despite its airpower and artillery advantages. Second, the Three Brotherhood Alliance potentially aligning itself more openly with the pro-democracy movement — at least militarily — highlights the resistance’s determination and coalition-building efforts… Considered together, the Myanmar military is more vulnerable than at any time in the past half century. Now is the moment for Myanmar’s pro-democracy resistance to push hard and for their international supporters to crank up the pressure on the junta. The resistance should continue to build momentum with operations across the country, while international backers like the United State[4] should increase the tempo of sanctions and redouble their diplomatic efforts to convince the junta that it cannot prevail.

The Tatmadaw is also having recruiting problems:

While the coup regime is losing territory due to armed conflict, they are also suffering defection, desertion, and recruiting problems. Given the dwindling of foot soldiers, the military has had to summon all veterans for one more tour of duty. An anonymous veteran said they are not allowed to refuse the call to duty except on health grounds. According to Captain Lin Htet Aung, who defected the military and joined the resistance movement, nearly 10,000 security forces—roughly 8000 soldiers and 2,000 policemen—have defected since the coup.

So, optimism? For a change?

National Unity Government (NUG)

The NUG is the successor to Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD), dissolved by the miltary after its coup in 2021 ended a ten year experiment in democracy, where the NLD represented the forces of democracy (and not very well, given the Rohingya debacle). Its strategy differs from NLD’s in key ways:

While the NLD had emphasised democracy before federalism, the NUG is prioritising federalism. It also exhibits greater inclusion of ethnic and other stakeholder interests, and views itself to be laying the foundation for “a federal union that seeks to address decades of structural violence against all the people of Myanmar regardless of race and religion”.

In particular, policy pronouncements made by the NUG includes a reversal of NLD-era statements that had defended atrocities committed by the military against the Rohingya.

Critcally, the NLD advocated non-violence. The NUG does not:

The People’s Defensive War – which the NUG announced on 7 September – may constitute the most controversial policy; the international community held mixed views and reactions to this move. Be that as it may, the NUG’s call to arms was widely welcomed, supported and acted upon across Myanmar. Its establishment of the People’s Defense Force (PDF) in May and the subsequent proliferation of many local PDF chapters/groups serve as a barometer of on-ground sentiments.

The NUG has achieved a considerable amount internationally:

The NUG has achieved diplomatic breakthroughs that most other parallel or exile governments could only dream of.

Myanmar’s ambassador to the United Nations has aligned himself with the NUG, which has the added benefit of effectively blocking the military junta from the world’s highest intergovernmental body.

The regime has also been excluded from high-level ASEAN summits, while the NUG’s foreign minister Daw Zin Mar Aung has publicly met with a number of prominent international government figures.

(The NUG also has offices on K Street in Washington, DC.)

The NUG is also, to a degree, self-funded (though it is not sovereign in its own currency and seems, oddly, not to have established a central bank). From the Stimson Center:

The opposition National Unity Government’s Ministry of Planning and Investment (MOPFI) [has] raised over $150 million in an innovative and tech-savvy manner through the auction of military-owned property and land preemptively seized under eminent domain, crypto bond sales, lotteries, sale of mining rights, potentially issuing shares in military-owned corporations, and now a full-service online bank. This has all been possible through their fintech savvy. The NUG has raised all funds in a licit manner as though they are the state they aspire to be.

(I think many would quarrel with the Stimson Center’s description of NUG as “the opposition,” since that implies that the junta is legitimate.) The MOPFI also, amazingly, runs a state lottery out of its digital wallet, NUGPay.

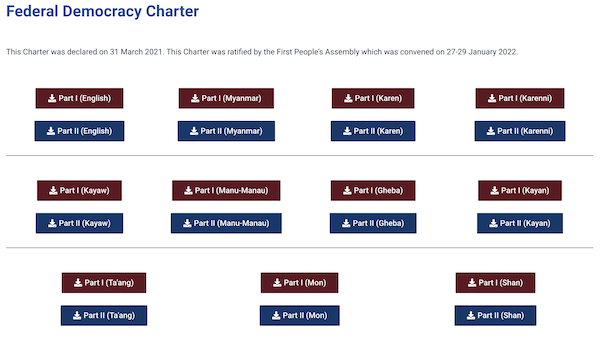

The NUG has also established a process through which a Constitution will be created, a sort of meta-Constitution, called the Democracy Charter. Here is the home page:

Note the multiple languages, which shows NUG’s commitment to the various ethnicities. Note also that the default language is English (and not Chinese).

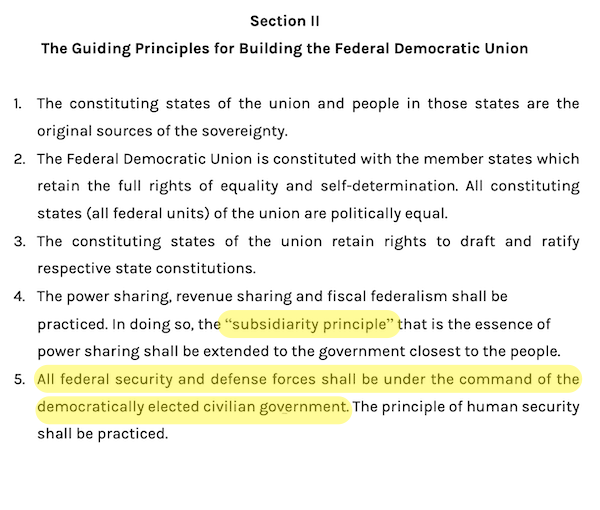

Here is one section of the Charter:

Point 4 is a real commitment to Federalism, probably the only way forward for Myanmar other than the Four Cuts. Point 5, however, points to the NUGs fundamental problem: How to achieve the monopoly of violence one expects the state to have. We saw above, for example, that the Three Brotherhood Alliance was not under the (civilian) command of the NUG.

Finally, the NUG is not headed by a charismatic figure. That may not be a bad thing (though it probably confuses the press and funders):

Myanmar resistance movements – note the plural – today do not have a single charismatic leader who can perform like Ukraine’s Zelensky, a TV actor-cum-politician. …[T]hat’s not a bad thing for Myanmar… [F]or a quarter of a century, we had Aung San Suu Kyi who had been likened with Mandela, MLK Jr., Mother Theresa, and Mohandas Gandhi. We know how that fairy tale of Mother of the nation ended – as the defender and denier of the genocide at the UN’s highest court in The Hague. She turned into a cultist figure, while her Bama-centric politics aligned with the genocidal military had further disunited Myanmar’s majoritarian and ethnic minority communities.

(Bama, or Bamar, is the ethnicity of central Myanmar, hegemonic in many ways.)

NGOs

I have to include this from The Irrawaddy, partly because it’s funny, but also because if there is an attempt to “broker a peace,” instead of letting the Myanmar resistance win, the NGOs will play their part, as analysts, spokesholes, etc. The scene is a local café, a Starbucks if there is one:

NGO Worker I: We had a real good series of peace workshops up in Kachin State in 2019, youth and women were enthusiastic! We were shifting the narrative, and focusing on inclusiveness. We had evidence-based surveys too that the workshops worked. Now, it would be relevant to do such workshops in Sagaing, where donors are interested in investing due to armed conflicts.

Of course, this reinforces my priors on NGOs!

Local Self-Governance

An important point to make is that much state-like organizing is happening on the ground, right now:

But NUG is NOT the alternative structure or even organization that will replace Myanmar’s murderous military. If international state actors are looking at the NUG – and reach the conclusion that it is not the winning horse capable of holding the strife-torn country together, they were looking for the answer in the wrong place.

Myanmar local communities of resistance, in collaboration with, yes, both NUG and the ethnic armed organizations, are building state structures from the ground up, in accord with the ethos of devolution or decentralization of local self-governance. Many of these local communities work with the Chin National Front, Kachin Independence Organization, Arakan Army, the Karen National Union, the Karenni National Progressive Party, and so on, who actively opposed to the coup regime. Even the Restoration Council of Shan State and the United Wa State Army have a functioning truce with the military in Naypyidaw run their own administration, without needing any nod from the military.

(Here is an argument that international organizations should assist these local organizations directly.) Subsidiarity, then, exists before a Constitution; indeed, the Constitution could be said to grow out of it, not the other way round.

EAOs/PDFs

The danger that, when the Tatmadaw implodes, the various EAOs will turn into warlords, instead of banding together in a Federal system, is so obvious I don’t need to state it. Goons, or statesmen? Time will tell. Less obvious is that the same dynamic applies with PDFs, which are not ethnic armies, but initiated (see above) by the NUG itself:

Local administrations in PDF strongholds, like Sagaing and Magway regions, are largely subordinate to PDFs, meaning there is little civilian oversight of the various armed groups. This has led to a rise on criminal activity linked to PDFs and NUG local administrators – including sexual assault, illegal logging and gambling dens.

And of course, private armies could proliferate as well:

Myanmar politics in the 1950s was defined by the rise of pocket armies – personal militias loyal to prominent politicians or businessmen. “They were used as personal security forces by politicians, and they engaged in violence and intimidation,” said the seminal 2016 Asia Foundation report on militias in Myanmar.

With hundreds of newly formed armed groups across Myanmar since the coup, this phenomenon risks returning and would make it harder for the NUG to reform itself. If some of its leaders go, they could take whole groups of armed men with them.

It’s hard for me to imagine that the principle of subsidiarity applies to armed groups, but I guess we’ll find out.

Conclusion

I hope this post at least gives you enough of a scorecard so you can tell the players apart! This video, with an energetic Myanmarese aerobics instructor going through her routine while, in the background, the Tatmadaw drives its armored vehicles up to Naypyitaw’s Parliament building, as they staged a coup, spawned innumerable viral takes and memes in 2021:

A woman conducted her aerobics class in Myanmar without realizing a coup was taking place. Behind her, a military convoy arrives at parliament, 2021.pic.twitter.com/YpO8Fr3qVB

— High on History (@High0nHistory) November 18, 2023

Wouldn’t it be nice to see the aerobics dancer make a sequel, in 2023 or 2024, with democratic forces marching out of the Parliament building? That would be a happy conclusion to our natural experiment. That, and if the good guys stayed good. So often they don’t.

NOTES

[1] The term “tatmadaw” is contested:

“Tatmadaw’ (တပ်မတော်) has long been adopted as the standard title of the Burmese military in journalistic and scholarly reports on Burma. The critics called on writers to replace the term with “sit-tat” (စစ်တပ်), which simply means “military” in Burmese…. Because of the laudatory nature of the royal particle daw (တော်) included in the term, critics say the continuous use of the term amounts to whitewashing over the crimes committed by the institution and even risks emboldening them to continue their abuses.

However, “tatmadaw” is what search wants, so that is what I will use.

[2] As far as China’s influence, the Myanmar people have views. From Lawfare, of all places:

Politics, though, is not an elite sport… [T]he rules of the game are forged over long stretches of time. In the clash of attitudes, expectations and entrenched interests, it is most important to note that Myanmar’s population is particularly wary (and weary) of Chinese influence. The country, for instance, is increasingly a safe-haven for China’s illicit industries. Over the past decade, Myanmar turned into one of the world’s largest hubs for methamphetamine production. This industry is a breeding ground for transnational Chinese syndicates, a revenue stream for various parties to the conflicts in Myanmar and a source of social unrest as addiction spiked along with the growing trade. Border-town casinos are meanwhile transforming into ‘smart cities’ fully separate from the Myanmar monetary system. Chinese interests are also evangelizing their intertwined notions of development and governance in the country’s largest cities, facilitating a massive surveillance system in Mandalay and pushing for a New Yangon City to house a swelling urban population. China’s development model is a strategic export; demand, though, is nascent, and popular resistance to any form of heavy-handed rule remains resolute across Myanmar. Since the coup, this popular skepticism has turned into speculation and fear-mongering about China’s role in supporting the military, leaving their interests in ever-more doubt. This doubt reached a fever-pitch when two Chinese-owned garment factories were burned earlier this month amid a military crackdown in Yangon’s poorest outskirts.

[3] Bad as they are, the Tatmadaw are not fascist, at least as Robert O. Paxton defines the term.

[4] Feh. From Foreign Affairs, June 2023:

[T]he 2023 BURMA Act… reiterates Washington’s goal of reversing the coup and calls for the provision of nonlethal military aid (mostly communications equipment) to antiregime forces. Yet the law mandates neither lethal military support nor sanctions on the junta’s oil and gas business, and even the disbursement of nonlethal aid has lagged. U.S. efforts on behalf of Myanmar’s rebels are negligible—practically nonexistent—in comparison with the support the United States is providing to Ukraine, for instance, in its war against Russia.