Yves here. Note that the notion that the Bank of England is independent is more due to deference than law.

For instance, Richard Murphy has repeatedly called for its Governor, Andrew Bailey, to be dismissed, which the Government could do at any time. Some detail from an October 19 post:

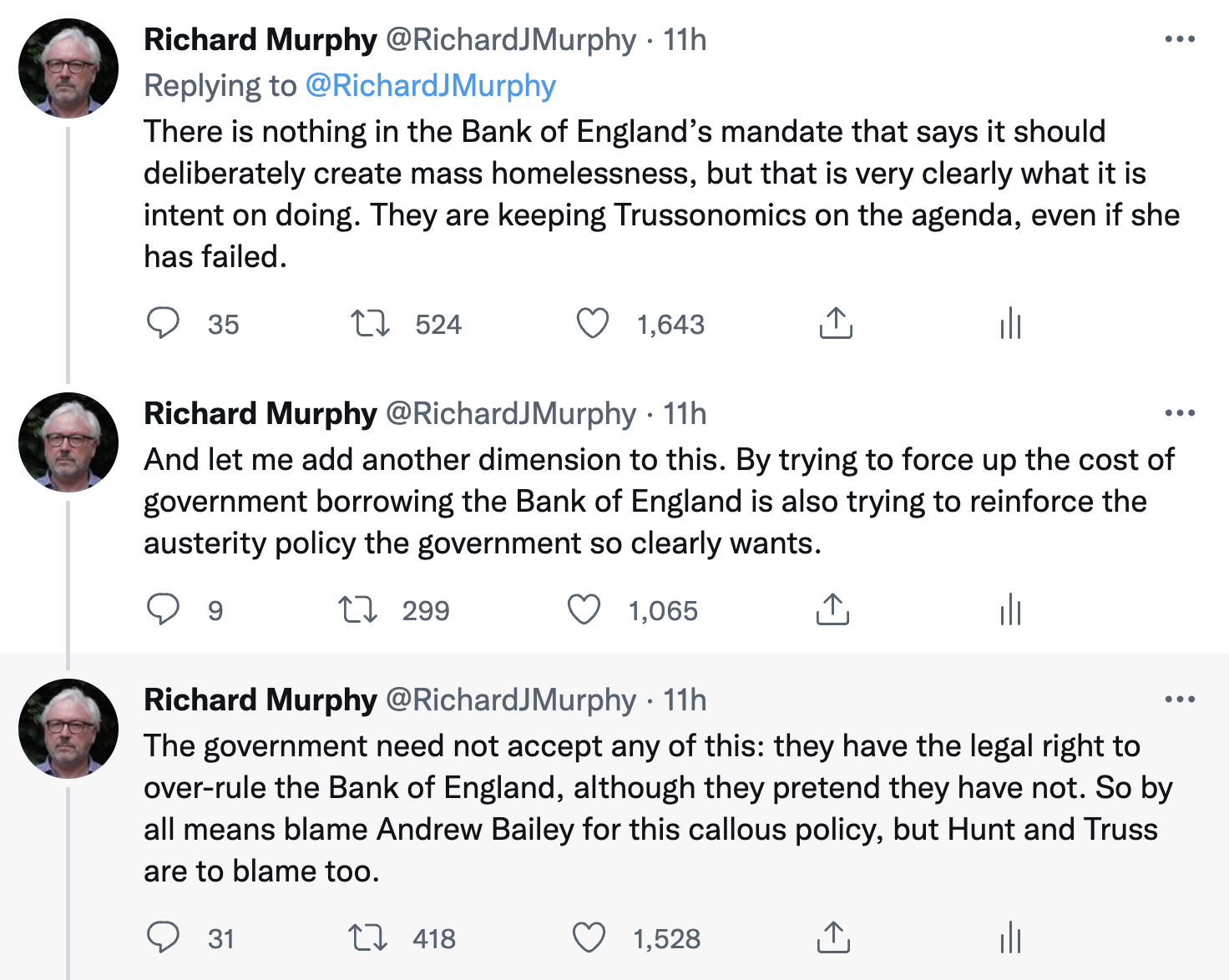

I posted this short thread on Twitter last night:

….There is class warfare going on in our economy right now. The financial elite is very obviously planning to devastate the well-being of the majority in the UK. I cannot explain this policy in any other way. Why else would quantitative tightening, a policy that can only have the goal of increasing the interest rate, be going on otherwise?

But let’s also address that austerity point as well. The government is saying it cannot borrow to pay for pension increases, social care, the MHS or decent education. But apparently, the capacity to sell binds into the market that could fund that does actually exist but is instead to be used to force up interest rates with no social benefits attached.

This is the Bank of England waging economic warfare on this country. I have no other way to describe it.

One hates to say it, but the point of a central bank is to serve as a bankers’ bank, as in above all protect the payments system and as needed, put down or rescue banks. As Perry Mehrling has pointed out, central banks also engage in war finance, a conflicting role. And as advanced economies become more financialized, central banks have been allowed or assigned mission creep and made the chief stewards of the economy, as executives and legislatures have either lost their nerve or been indoctrinated to believe that magical Mr. Market is best left to his own devices. That leaves central banks to move into the resulting authority vacuum when things get ugly.

By Andrew Fisher, Labour’s executive director of policy, oversaw the production of the 2017 and 2019 Labour manifestos. He is now a columnist for the i paper. Originally published at openDemocracy

Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey has been increasingly hawkish on interest rate rises in recent days, saying “inflationary pressures will require a stronger response” and he “will not hesitate to raise interest rates”.

The bank’s monetary policy committee (MPC) will meet on 3 November to set the Bank of England base rate (the rate of interest charged by the bank to commercial banks). Expectations are that there could be a sharp rise from the current 2.25%, to which it was increased in late September.

Interest rate rises are damaging on a number of levels. For government investment, it means borrowing at higher rates – bad news when the nation’s debts (currently £2.36tn, or 99.6% of GDP) are rising. It also means spending a growing share on debt interest.

But my major concern is for households. The current hike in interest rates means the average mortgage holder who may have got a two- or five-year fixed rate mortgage at around 1.6% interest will instead be paying around 6% when they come to renew their fixed rate term. That leap in interest rate adds around £500 a month to the average UK mortgage, and that rises to an extra £915 in London.

Interest rate rises also widen inequality as poorer people are more likely to be in debt (and to be at risk of problem debt), while rich people are more likely to have savings that benefit from higher interest rates.

So when the MPC meets in two weeks’ time, they will hold in their hands the lives of millions of people who are struggling to make ends meet.

Tony Benn’s quintet of questions are pertinent here: “What power have you got?”, “Where did you get it from?”, “In whose interests do you use it?”, “To whom are you accountable?” and “How do we get rid of you?”

Independent Since 1997

The Bank of England has power over interest rates, and that power was granted by the incoming New Labour government in 1997. Operational independence meant the bank had control of monetary policy – the power to set interest rates and, though not foreseen at the time, the power to intervene through measures such as quantitative easing.

Previously, the chancellor had held a monthly meeting with the governor of the Bank of England at which interest rates were agreed.

Independence for the bank had been the aim of Thatcher’s longest-serving chancellor, Nigel Lawson. He wrote in his memoirs: “Politicians, however austere they may be, are subject to electoral pressures which will be thought, rightly or wrongly, to affect their judgement.”

This idea – that decision-making about the bank should be independent of “electoral pressures” – is profoundly anti-democratic. Interest rates have political consequences on the electorate, so why shouldn’t democratic pressure be brought to bear on those that set them?

Bank of England independence was created in an era of relatively stable growth, rising living standards and high employment, with a government that was reducing poverty. The bank’s mandate was simple: to target inflation at 2% – a largely arbitrary figure – to help consumers and businesses plan.

We are far from that world. The banking crash, austerity, Brexit, the coronavirus pandemic and the energy price spike have all caused significant and ongoing hits to the UK economy – each crisis compounding the last.

On several occasions these crises have necessitated significant policy co-ordination between the government of the day and the Bank of England – most notably during the banking crisis and then during the pandemic, when Andrew Bailey, sounding more like a politician, intervened, saying: “We can help to spread over time the cost of this thing to society… We have choices there and we need to exercise those choices.”

Economic crises have necessitated the politicisation of the Bank of England. Far from technocratically fiddling with interest rates to move steadily towards target inflation, the bank has been in a semi-permanent state of monetary activism for 15 years.

Ed Balls, who as a special adviser to new chancellor Gordon Brown was one of the architects of delivering Bank of England independence in 1997, wrote nearly 20 years later: “As these unelected, technocratic, institutions become increasingly powerful, the pre-crisis academic consensus around central bank independence – put crudely, ‘the more, the better’ – has become inadequate.”

Repeated crises and the need for a more interventionist monetary policy has led central bankers into political terrain, with former Bank of England governor Mark Carney frequently enraging Brexiteers with his public comments on the impacts of leaving the EU. Likewise, his successor Bailey angered unions when he told workers to show “restraint” in their pay demands.

Bank of England independence was created in a world that no longer exists. The decisions the MPC will make in the coming months will affect the lives of millions of people – and should not be made by unaccountable technocrats.

But more importantly, pulling on the interest rate lever will not help solve inflation. Interest rate rises dampen inflation by reducing excess demand and encouraging saving. But in the UK today, demand is already weak: incomes are falling and retail sales are collapsing. Further reducing it now by raising mortgage costs and making it more expensive to borrow will only deepen the coming recession, as consumers end up spending more on mortgage and debt costs, meaning they have even less to spare for sectors like retail, hospitality and leisure.

The problem for the ‘independent’ Bank of England is that it does not have access to the levers that could properly help to control inflation – price caps, rent freezes, windfall taxes. Those rightly sit with elected politicians.

One could reform the Bank of England’s mandate, broadening the criteria for decision-making on interest rates from simply targeting inflation to “including [the impact of interest rates on] growth, employment and earnings”, as former shadow chancellor John McDonnell advocated.

At this moment of profound economic and social crisis, the bank risks becoming demonised for worsening the economy. It may not be in the bank’s interests, either, to maintain independence.

As the great British economist John Maynard Keynes said: “When the facts change, I change my mind.” Whatever the past merits, Bank of England independence in its current form is neither good for the economy, nor for the people nor for the bank itself.

The bank and its MPC should have an advisory role – but in a democracy the government must weigh up wider issues. It needs a co-ordinated policy to tackle inflation that involves more than just the (currently) impotent lever of interest rates.