About an hour after news broke Thursday that former President Donald Trump had been indicted by a Manhattan grand jury, Yusef Salaam released a one-word statement on Twitter:

“Karma.”

If all goes as we now expect it, Donald Trump may be in a New York City courthouse by Tuesday, to be processed as a defendant, to face charges. Salaam knows what that’s like.

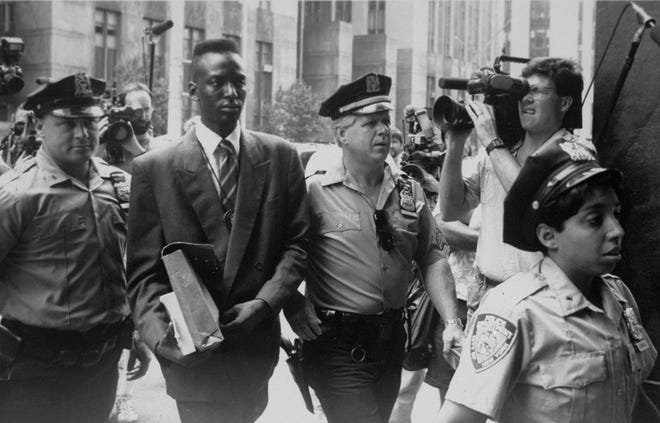

Salaam was one of the five boys wrongly accused of gang raping a female jogger in New York’s Central Park in 1989. That’s when his life first intersected with Donald Trump’s.

Trump – at the time, he was a flashy developer, not a reality TV host and definitely not a president – took a personal interest in the case, enough to take out full-page advertisements in four New York City newspapers calling for the death penalty after the attack. It was an early form of Trump rhetoric, and it helped fuel the public outcry that thirsted for a conviction in the case.

That conviction happened. The men were commonly referred to as the Central Park Five.

But they would eventually become known as the Exonerated Five.

Salaam is thinking about that this week, as we learn that the now ex-president faces a criminal indictment. But he isn’t thinking about it as a feel-good moment.

And he isn’t thinking about how Trump may now experience some of the same things – a booking, a court hearing, a wait for a verdict – that he once experienced.

He’s thinking about the differences.

“In this instance, with Donald Trump being indicted, he gets to be afforded the opportunity for the justice system to work for him – to be seen as innocent until proven guilty,” Salaam told me Friday. “To truly be able to mount the proper defense that has eluded so many of us.”

The Central Park Five and a conviction reversed

Salaam, Raymond Santana, Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray and Korey Wise were all boys in 1989, when they were convicted of raping a woman who had been found brutally beaten after going for a late-evening jog through Central Park.

That the victim was white and all five boys were Black and Latino made the case that much bigger in a city that was already wound up tight over the issue of crime, an issue that would only wind tighter in the stop-and-frisk policing era of the years that followed.

But in 1989, Trump was making his name synonymous with New York, so when he spent $85,000 for ads that screamed: “BRING BACK THE DEATH PENALTY AND BRING BACK OUR POLICE!” people noticed.

Trump claimed that the city was being “ruled by the law of the streets, as roving bands of wild criminals roam our neighborhoods, dispensing their own vicious brand of twisted hatred on whomever they encounter.”

“They should be forced to suffer and, when they kill, they should be executed for their crimes. They must serve as examples for their crimes,” he wrote. “They must serve as examples so that others will think long and hard before committing a crime or an act of violence.”

New York had not held an execution in decades, but the five boys were indeed convicted, and they served. Salaam spent much of his adolescent years behind bars; nearly seven years in prison.

In time, they served as examples, too, but examples of something else: The wave of people wrongfully convicted and sent to prison in America, only to be exonerated years or decades later by DNA evidence.

That all five boys where Black and Latino made the case look, well, just that much more like so many others.

Life after exoneration

The men’s names weren’t cleared until 2002, after convicted murderer Matias Reyes confessed to the assault. The boys has been coerced into confessing. Reyes’ admission was confirmed by DNA evidence. The city awarded the men $41 million in 2014, a decade after some of them sued for violation of civil rights.

During his presidency, Trump refused to apologize for his actions in 1989.

Salaam said it was difficult watching Trump ascend to America’s highest office. This was, after all, the man who once seemingly called for his execution.

Trump’s platform as the leader of the free world, his perceived power and success, has served as a constant reminder of the injustices Salaam faced at age 15.

He told me he would often ask himself: “How are you supposed to move in that space? How do you live? Hiding from anything and everything?”

“You have to literally get up and do what’s necessary in the moment,” he said.

Salaam is 49 now. He works now as a criminal justice reform advocate and is running for New York City Council.

He speaks in the complex sentences of a man whose entire existence has been a living experiment in the most complex tests of justice. He will never be able to separate himself from his time in prison, but he feels empowered to help others avoid a similar experience.

“We live in a system where the justice system seems like there is no justice when it comes to Black and brown bodies,” Salaam told me. “It seems like there is no justice, but there’s a sliver of it there, the opportunity for there to be a justice system that works for all people, one with the same equity that we’ve been crying out for. We want a system that works.”

“Seeing the indictment come down, reading about it and breathing the newness of it and all the possibilities of what it could be, what it could represent, said to me that this is a new day,” he said. “This could be a new time – the era of justice.”

The Trump ads from 1989 feel familiar in their all-caps indignation. These days, he often laments that he’s “the most persecuted person in the history of our country.”

I believe Salaam and those four other men might like to have a word with him about that. They are familiar with the idea of being persecuted – and prosecuted – for a crime they didn’t commit.

At least one word.

Karma, indeed.

Suzette Hackney is a national columnist. Reach her on Twitter: @suzyscribe.