The roughly $25 billion planned merger of Kroger and Albertsons, unveiled in October with much fanfare, promised a new entity that would “serve America with fresh, affordable food.”

The deal would create a company with nearly 5,000 stores reaching about 85 million households across the U.S. and with a share of the U.S. grocery market second only to that of Walmart Inc. WMT, +0.18%.

Food companies have enjoyed record earnings throughout the pandemic thanks to their ability to raise prices, according to a new report from Accountable.US, a liberal-leaning advocacy group. Kroger Inc. KR, -1.74% and Albertsons Cos. ACI, +1.63% have been part of that trend, even as they have generously rewarded shareholders.

“Even before this potential merger, the oligopoly of U.S. grocery giants has been needlessly nickel-and-diming working families — marking up prices over and over despite reporting huge profits,” said Liz Zelnick, spokesperson for Accountable.US.

See: Walmart is still seeing ‘strong’ demand and spending, its U.S. CEO says

As many as 42 million Americans said in January 2022 that they could not afford to buy enough food, according to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. That was about double the number who said the same in April 2021, before pandemic-linked stimulus programs ended.

“The industry chose to enrich a small group of investors with generous handouts rather than keep prices stable on everything from bread to baby formula,” said Zelnick. “Even less competition under this proposed deal will only lead to more unfettered corporate greed at the expense of millions of consumers — and that’s why it deserves serious scrutiny from Congress.”

Think rising inflation means companies are forced to raise their prices? As WSJ’s Dion Rabouin explains, it actually works the other way around: Corporations drive inflation, and data show that they have been pushing up prices and will continue to do so for some time. Illustration: Elizabeth Smelov

A review of recent earnings from Kroger and Albertsons and of comments from executives on earnings calls shows how the companies have been dealing with the current high-inflation environment.

In December 2021, for example, Kroger Chief Financial Office Gary Millerchip told analysts the following on the company’s third-quarter earnings call: “We are passing along higher costs to the customer where it makes sense to do so.”

In March 2022, Kroger posted record earnings for 2021, chalking up $1.66 billion in net income. The company spent a bigger sum — $2.2 billion — on stock buybacks and dividends that year.

Don’t miss: Why did inflation surge to a 40-year high? Here are 4 causes of the worst monetary-policy mistake in years.

In June of that year, on the company’s first-quarter earnings call, Millerchip said this, according to a FactSet transcript: “We are operating from a position of financial strength and we’ll continue to evaluate opportunities to deploy excess cash to accelerate our growth model and deliver sustainable total shareholder returns.”

In September, Kroger posted roughly $1.4 billion in net income for the first half of the year, a 130% jump over the same period a year earlier. It spent more than $1.28 billion on stock buybacks and dividends in the same period.

Source: Kroger

Kroger responded to a request for comment by noting its long track record of investing to lower prices following previous mergers and acquisitions while maintaining strong financial performance. It pointed to its recent merger with Harris Teeter as an example.

“Our ability to deliver value to customers, communities and shareholders is rooted in our business model that emphasizes lowering prices to expand our customer base,” a spokesperson wrote in emailed comments.

“We intend to build on this track record following our proposed merger with Albertsons and are committed to investing $500 million to reduce prices and $1.3 billion to enhance the customer experience.”

In total, those investments would equal about half of what the company has given back to shareholders over the past 18 months.

Albertsons, which did not respond to a request for comment, has admitted to price hikes more than once since late 2021.

In its fourth-quarter 2021 earnings call, for example, CFO Sharon L. McCollam credited “retail price inflation” as contributing to strong results.

In April 2022, Albertsons posted record net income for 2021 of $1.6 billion. “Our strategy is working, and we are executing well against industry-wide pressures,” Chief Executive Vivek Sankaran said in a statement.

In July 2022, Albertsons had first-quarter net income of $484 million, up 9% from the same period the previous year. At the same time, it raised dividends by 35% to $63 million, with Sankaran praising a “strong operating and financial performance across all key metrics.”

Albertsons

The issue has caught the attention of a bipartisan group of attorneys general, who are urging Albertsons to hold off on a nearly $4 billion special dividend payment until regulators complete a review of the proposed merger with Kroger.

The dividend could become a “massive improper giveaway to certain shareholders,” said Karl Racine, attorney general for the District of Columbia, in an interview on CNBC’s “Squawk Box” on Wednesday. Paying that to shareholders could weaken Albertsons’ ability to compete in a “very, very tough marketplace” should the merger fail to go through, Racine added.

On Wednesday, the attorneys general of California, Illinois and the District of Columbia sued Albertsons to stop the payout, the Associated Press reported. The lawsuit, filed Wednesday in U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C., is the second this week seeking to delay the dividend payment. The state of Washington’s Attorney General Bob Ferguson filed a similar lawsuit in state court Tuesday.

Boise, Idaho-based Albertsons said Wednesday that both lawsuits are without merit.

To be sure, Kroger and Albertsons are facing obstacles to their deal, not least of which is persuading regulators that the merger will increase competition even as it further consolidates the market.

The companies have said they are willing to sell stores to rivals to ease concerns about stifling competition.

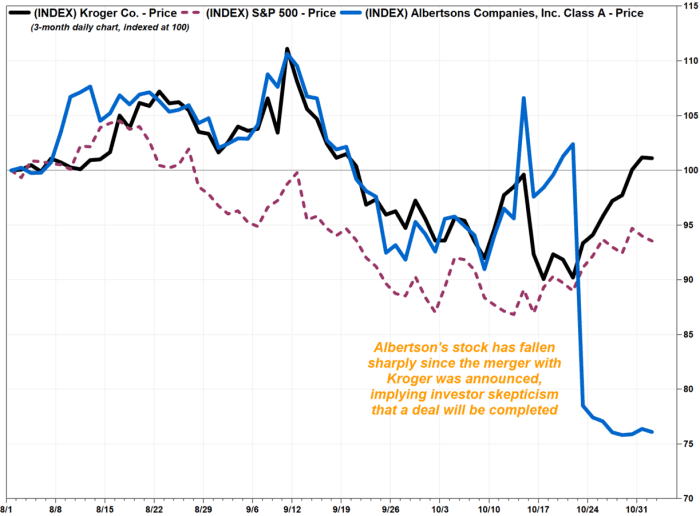

Albertsons stock has tumbled nearly 30% since the merger was announced, implying skepticism among investors that a deal will be completed.

FactSet, MarketWatch

But the companies have already been aggressive and active acquirers of smaller retailers, with at least $19.5 billion in deals since 1998, according to data crunched by the New York Times. The biggest deal was Albertsons’ $9.4 billion takeover of Safeway in 2014.

Those moves have already consolidated the sector, irking consumer advocates and drawing criticism from Sens. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Bernie Sanders of Vermont.

“Americans don’t need another mega-grocer,” said Stacy Mitchell, co-director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a nonprofit organization that advocates against corporate control, in a statement following the deal announcement.

“Kroger and Albertsons together would control nearly 20 percent of grocery sales in the U.S. That’s on par with Walmart, whose power in food retailing has done widespread damage to communities, farmers, food workers and local grocers,” Mitchell said.

The new company would also have more clout in dealing with suppliers, allowing it to strike deals that would push up costs for independent grocers, she said.

“If it’s allowed to go through, this deal would almost certainly put more rural towns and Black and Latino neighborhoods in cities at risk of becoming ‘food deserts’ as more local grocers are driven out of business,” Mitchell said in the statement.

Albertsons shares are down about 18% in the last month. Kroger shares have gained about 8%, matching the S&P 500’s SPX, +1.36% gain.