Market instability is the biggest risk to central banks globally, replacing inflation, owing to massive amounts of leverage.

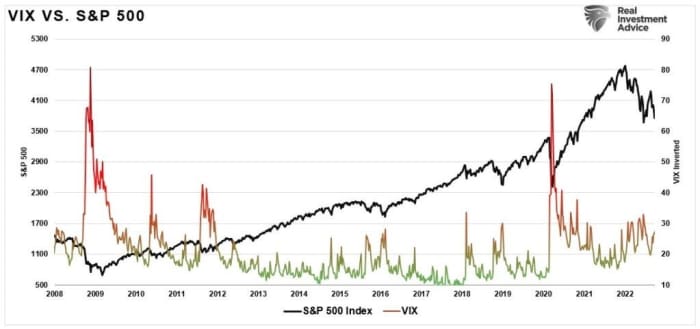

So far, the U.S. Federal Reserve is fortunate because there’s low volatility in the stock market SPX, -1.51%, even though there’s a bear market. Market stability affords the Fed the space needed for the most aggressive rate-hiking campaign since the late 1970s.

However, stable markets can become unstable rapidly when something breaks due to rising rates or volatility. The Bank of England (BOE) is a current example of what happens when things go awry. The BOE on Wednesday was forced to start buying bonds to solve a potential crisis with U.K. pension funds. The pension funds receive margin when yields fall and post additional collateral when yields rise.

As they have recently, the pension funds are hit with margin calls, which have the potential to cause market instability. Due to leverage built up through the financial system, market instability can spread like a virus through global markets. That’s what happened in 2008 with the Lehman crisis.

Is the BOE’s actions an isolated event, or will the Fed be the next central bank to reverse its monetary policy?

Recession pending

The Federal Reserve said it’s deeply committed to its aggressive campaign to quell surging inflation. As Chairman Jerome Powell said at the Jackson Hole Summit in August:

“[A] failure to restore price stability would mean far greater pain.”

Still, the Fed doesn’t want to cause a recession. That may be a challenge for two reasons:

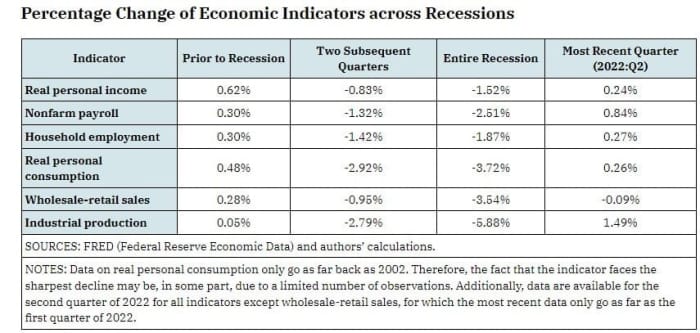

- The Fed remains focused on lagging economic data, such as employment, which are highly subject to future revisions.

- Changes to monetary policy do not show up in the economy until nine to 12 months in the future.

Therefore, as the Fed is hiking rates based on lagging economic data, the risk of a policy mistake becomes heightened. By the time economic data deteriorate, the preceding rate hikes have yet to impact the economy, which eventually deepens the recession.

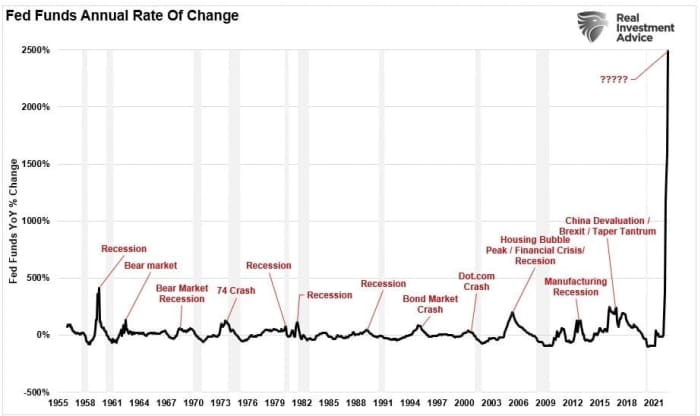

As shown, the annual rate of change of the fed funds rate is now at a record. However, every previous rate-hiking campaign has led to a recession, bear market or other economic event.

Remember, the Federal Reserve does not operate in an economic vacuum. Other factors contribute to the tightening of monetary policy and the impact on economic growth. When those other factors, such as higher interest rates, falling asset prices or a surging dollar, coincide with the Fed’s policy campaign, the risk of “market instability” increases.

Policy mistake in the making

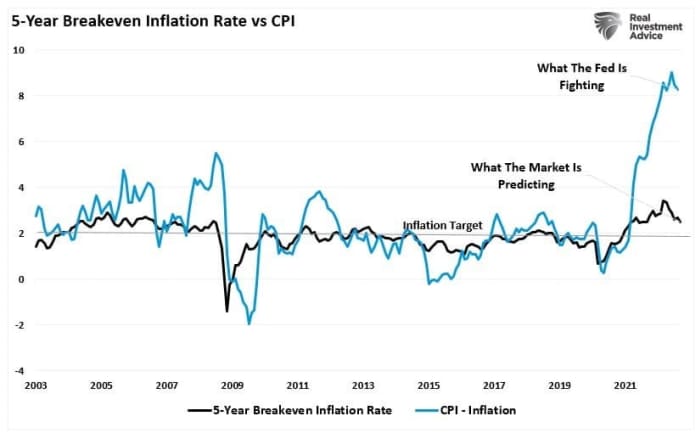

The current bout of inflation is vastly different than that of the late 1970s.

Economist Milton Friedman once said that companies don’t cause inflation; governments create inflation by printing money. There was no better example of this than the massive government interventions in 2020 and 2021 that sent subsequent rounds of checks to households, creating demand, when an economic shutdown constrained supply due to the pandemic.

The following illustration is taught in every economics 101 class. Unsurprisingly, inflation is the consequence if supply is restricted and demand increases by providing stimulus checks.

As the Fed is viewing, in part, lagging economic data, forward estimates for inflation are falling quickly. That’s because the economy is faltering as liquidity dries up.

Historically, the best cure for high prices is high prices, as the saying goes. In other words, inflation would resolve itself as high costs curtail consumption.

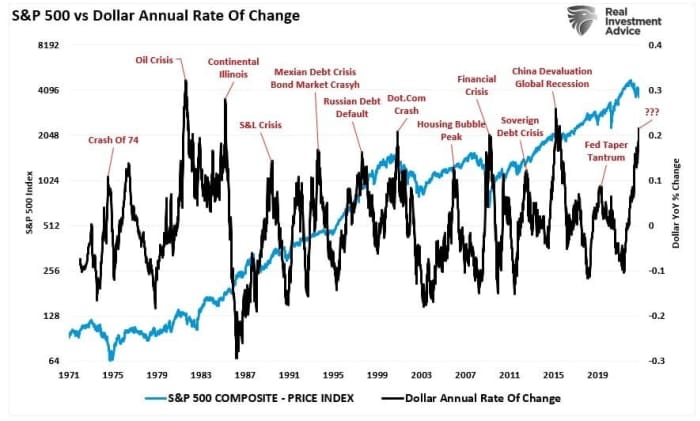

But the financial system is complex. Interest rates and the dollar have increased dramatically in recent months, applying further downward economic pressure by raising costs domestically and globally. Not surprisingly, sharp annual increases in the dollar are coincident with market instability and economic fallout.

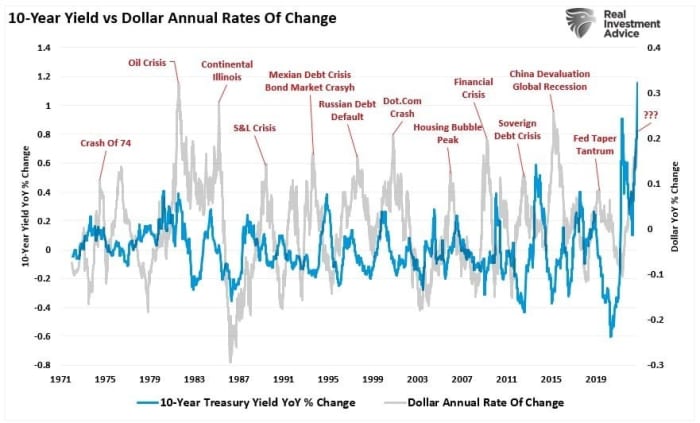

Furthermore, the surge in the dollar, driven by higher rates, accompanied the sharpest increase in interest rates in history. That’s problematic, particularly in heavily indebted economies, as debt-servicing requirements and borrowing costs surge. Interest rates alone can destabilize an economy, but when combined with a surging dollar and inflation, the risks of market instability increase markedly.

The Fed will blink

After more than 12 years of the most unprecedented monetary policy program in history, the Federal Reserve has put itself into a poor situation. Policy makers risk an inflation spiral if they don’t hike rates to quell inflation. If the Fed hikes rates to kill inflation, the risk of a recession and market instability increases.

The behavioral biases of individuals remain the most serious risk facing the Fed. For now, investors have not “hit the big red button,” which gives the Fed breathing room to lift rates. However, the BOE discovered that market instability surfaces quickly when “something breaks.”

When will the Fed find the limits of its monetary interventions? We don’t know, but we suspect they have already passed the point of no return, and history is an excellent guide to the adverse outcomes.

- In the early 1970s, it was the “Nifty Fifty” stocks.

- Then Mexican and Argentine bonds a few years after that.

- “Portfolio insurance” was the “thing” in the mid-1980s.

- Dot.com-anything was an excellent investment in 1999.

- Real estate has been a boom/bust cycle roughly every other decade, but 2007 was a doozy.

- Today, it’s real estate, FAANNGT, debt, credit, private equity, SPACs, IPOs, “meme” stocks — ” everything.”

For the Federal Reserve, inflation is the enemy it must defeat. However, while high inflation is detrimental to economic growth, market instability is far more insidious. That’s why the Fed rushed to bail out banks in 2008.

Unfortunately, we doubt the Fed has the stomach for “market instability.” As such, we doubt they will hike rates as much as the market currently expects.