Yves here. There is so much personality-driven reporting on Elon Musk, which the billionaire cultivates, that the resulting high level of noise means it takes a lot of work to parse out the signal. This post reviews the controversy over Musk’s ginormous stock option grants, which shareholders did approve in the end, and shows how the business press has gotten the story substantially wrong.

By Matt Hopkins, Senior Researcher, The Academic-Industry Research Network and William Lazonick, Professor of Economics at University of Massachusetts Lowell and President, The Academic-Industry Research Network. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

Musk’s Stock-Option Bonanza

On June 13, 2024, Tesla shareholders voted by a margin of almost four to one to re-ratify a bounteous stock-option package that the Tesla board of directors had granted to CEO Elon Musk in 2018, but which the Delaware Court of Chancery had rescinded five months earlier. With that grant in place, Musk can exercise, at a time of his choosing, 303,960,630 options to purchase Tesla shares at a strike price of $23.33. Tesla’s closing stock price on June 13 was $182.47. If, hypothetically, Musk had exercised these options on June 13, he would have reaped realized gains of $48.4 billion before taxes and $30.5 billion after taxes.

In an age when the public has become used to sky-high CEO compensation, the unprecedented size of Musk’s potential haul is, by comparison, in outer space. In both the Delaware court and the media, the question has been whether it is fair for one person, who was already among the richest in the world, to be paid so much. That focus of the debate, however, misses the purpose of the 2018 option grant and its deeper implications.

While it takes the form of a pay package, the point of the 2018 option grant is to enable Musk to secure his control over the allocation of Tesla’s resources by increasing his voting power in the corporation. From this perspective, the overriding issue is how Musk will use—or abuse—his control of the world’s leading EV producer. Anyone concerned with the EV transition should be asking whether Musk as Tesla’s CEO will make resource-allocation decisions that support value creation in the form of higher-quality, lower-cost EVs or, to the contrary, simply enable value extraction that results in financial predators, possibly including Musk, becoming wealthier than they already are.

We begin our analysis of this critical question by, as a first step, explaining why the stock-option packages that CEO Musk was granted in 2009, 2012, and 2018 have been the mechanisms by which he has been able to increase his voting power at Tesla. Then we document how, through the accumulation of Tesla shares, Musk’s percentage of voting power at Tesla has changed over the past 15 years. We outline how, in the era of “maximizing shareholder value”, financial predators can challenge Musk’s control of Tesla in ways that undermine EV innovation. That discussion raises the question of why Tesla, with Musk in control, did not adopt dual-class shares or delist from the stock market as ways of shielding its CEO from the “market for corporate control”. Finally, we ask whether, for the sake of the EV transition, Musk should remain Tesla’s CEO.

Musk’s CEO Compensation

For all the attention bestowed on Musk’s compensation, almost all media outlets, think tanks, labor unions, and academics routinely report an erroneous measure of his stock-based pay, based on “fair value” accounting. Fair-value measures of stock-based executive compensation produce estimates of the value of the stock options and stock awards based on grant-date stock prices. But, as we have explained in several publications,[1] the point of stock options and stock awards is to incentivize executives to make decisions that increase the company’s stock price in the future. Insofar as the stock price rises from the date of the grant to the date when the stock option is exercised or the stock award vests, executives are rewarded financially by realized gains.

It is the realized gains from stock-based pay, not the made-up fair-value measure, that flow into the executives’ bank accounts and on which they pay personal taxes (generally at ordinary tax rates) to the U.S. Treasury. Moreover, it is the realized gains on stock-based compensation that the employing corporation treats as a compensation expense in its tax filings. In Elon Musk’s case, the dramatic difference between the two measures of executive pay is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Elon Musk’s total compensation, with fair value vs. realized gains measures of stock-based pay, 2009-2023

For the 15 years from 2009 through 2023, Musk’s actual realized-gains pay was $24.8 billion, while his estimated fair-value pay was less than one-tenth of that amount. In most years, under either measure, his only compensation was a salary ranging from $24,000 to $56,000, and from 2020 to 2023, he declined to accept that token of Tesla’s appreciation. No matter. A 2009 stock-option package, with a fair value of about $24 million yielded Musk realized gains of $1.3 billion when he exercised the options in 2016, while a 2012 stock-option package with a fair value of $78 million yielded him realized gains of $23.5 billion when he exercised them in late 2021, toward the end of their ten-year expiration date.

Musk’s 2023 compensation of $1.9 million (chump change for him) resulted from his exercise of two 2013 option grants as part of Tesla’s company-wide patent incentive program, with a ten-year expiration date. He exercised the options in 2023, acquiring 10,500 shares with an average realized gain of about $177 per share.

The 2009, 2012, and 2018 stock-option grants required that, as conditions for the shares to vest, Tesla would have to succeed, under Musk’s leadership, in developing, manufacturing, and selling innovative EVs. In 2009, Musk received a split-adjusted 101 million options to purchase Tesla’s stock, equal to eight percent of Tesla’s outstanding shares, conditional on the development and rollout of the Model S, Tesla’s second-generation EV. In 2012, as Musk’s 2009 grant was close to fully vested, he was granted 79 million shares in stock options, equal to five percent of Tesla’s outstanding shares. The options vested if and when Tesla completed the development and rollout of the Model X and the Model 3 and succeeded in manufacturing a cumulative total of 300,000 vehicles. His one financial target was to achieve 30 percent gross margins for four quarters—a metric never met. The 2018 stock-option grant would vest in 12 tranches over time if Tesla’s growth reached escalating targets for revenue, adjusted earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), and market capitalization.

It should be noted that most stock-option packages granted to senior executives in the United States vest over periods of one to four years from the date of the grant without any additional metrics added as vesting requirements. If the stock price rises above the exercise (grant-date) price, the executives can realize gains from exercising the options, even if the stock-price increase results from the use of, for example, stock buybacks to give the price a manipulative boost. In contrast, vesting conditions of all three of Musk’s option packages have been largely related to the success of Tesla’s innovation strategy.

Use of the fair-value measures ignores the incentive design and function of Musk’s stock options, resulting in glaring errors in reporting his actual pay. For example, in its annual report on the “100 Most Overpaid CEOs” for 2021, based on fair-value measures, the progressive think-tank As You Sow fails to include Musk in their list because their use of fair-value accounting records his 2021 compensation as zero. In fact, it was $23.5 billion, as Musk exercised his options from his 2012 grant.

Moreover, As You Sow will never capture that $23.5 billion—by far the biggest payday of any CEO in history thus far—in any of its future reports. In making this error, As You Sow is not alone. For example, in its report on the 2021 pay of CEOs of companies included in the S&P 500 Index, the Wall Street Journal places Musk dead last at $0. That is, frankly, absurd.

It gets worse. In presenting its list of the highest-paid executives in 2021, the New York Times published an article, “How Elon Musk helped lift the ceiling on C.E.O. pay,” which refers to the fair value of Musk’s 2018 option package but ignores his actual 2021 income from his 2012 grant. To add to the confusion, an Associated Press story makes the illogical comparison between Musk’s potential realized gains of $44.9 billion from the 2018 option package and the median fair-value measure of the 2023 pay of CEOs of companies included in the S&P 500 Index.

With a fair value of $2.3 billion, Musk’s 2018 stock-option package undoubtedly encouraged other companies to increase their stock-option and stock-award grants to their senior executives (as the New York Times argued in its story of the highest-paid executives in 2021). By the end of 2023, Tesla had achieved the vesting requirements of the 2018 grant, but Musk has chosen not to exercise the options. Hence, thus far, he has no realized gains from them. Yet, in the recent discussions of whether Tesla shareholders would reapprove his 2018 option package, the media, pundits, and analysts have placed their value at around $50 billion, a realized-gains measure, based on the difference between Tesla’s prevailing stock price and the grant-date stock price. As You Sow, Wall Street Journal, New York Times, and other organizations that rely on fair-value measures will never report Musk’s actual realized gains from the reapproved 2018 package—not even when, probably close to their expiration date of January 19, 2028, Musk decides to exercise the options.

Given that Musk has not yet realized any gains on his 2018 options package, does that mean that he is short of cash? Hardly. In addition to his stock-option packages, Musk has “founder shares” that he received for investing $315.8 million in Tesla, almost all in the earlier years of the company’s existence. At Tesla’s closing stock price of $182.47 on June 13, 2024, these shares would have been worth $81.9 billion. If Musk needs cash—as was the case in 2021-2022 when he sold shares to help fund his purchase of Twitter—the high liquidity of the stock market means he can easily sell his shares at a time of his choosing.

In fact, however, to maintain his voting power, Musk seeks to avoid selling his Tesla shares. As an alternative, he borrows money, using shares as collateral. On December 4, 2020, Musk had borrowed $515 million against 265.0 million Tesla shares, which had a market value on that date of $52.9 billion—more than 100 times the amount of the loans on those shares. On April 19, 2024, Musk had 238.4 million shares pledged for loans, equal to $43.5 billion at Tesla’s stock price on June 13, 2024.

Along with the fact that he is CEO or a major shareholder of other companies, where he can also sell, or borrow against, his shares, Musk neither needs nor depends on drawing regular compensation from Tesla to pay the bills–particularly since he has sold off all his mansions and now lives in his tiny home in Texas.

Musk’s Corporate Control

As much as Musk’s stock-option packages have made him wealthier, for him, stock options have never been primarily about compensation. They have been about substantially shoring up his voting control at Tesla as the company fulfilled its “master plan” of developing, manufacturing, and selling a succession of innovative and increasingly affordable EVs.

What was at stake for Musk in the vote to reapprove his 2018 stock-option grant? Just listen to him; he is far more prone than other CEOs to say the quiet part out loud. On January 15, 2024, he X-posted:

The reason for no new “compensation plan” is that we are still waiting for a decision in my Delaware compensation case…I put “compensation plan” in quotes, because, from my standpoint, this is primarily about ensuring the right amount of voting influence at Tesla.

Musk claims that he needs the voting power of 25 percent of Tesla’s outstanding shares to be “influential”, but “at 15% or lower, the for/against ratio to override me makes a takeover by dubious interests too easy.” Musk would have easily attained 25 percent voting power at Tesla had he not sold his shares to buy Twitter.

At most publicly listed companies, a CEO with 50.1 percent of shares outstanding, each with one vote, could hand-pick their board of directors and exercise absolute control over the company’s strategy. Dissenting shareholders would not have sufficient votes to oust the CEO or to challenge their decisions. At Tesla, which has one vote per share but requires a supermajority to confer such power, Musk would need 33.4 percent of the shares outstanding to be, in effect, invulnerable to attack. With 25 percent of shares, Musk would enjoy de facto control of Tesla. Reduced to 13 percent as a result of the Delaware court’s rescission of the 2018 option grant, however, Musk’s strategic control would have been much more vulnerable to shareholder activism.

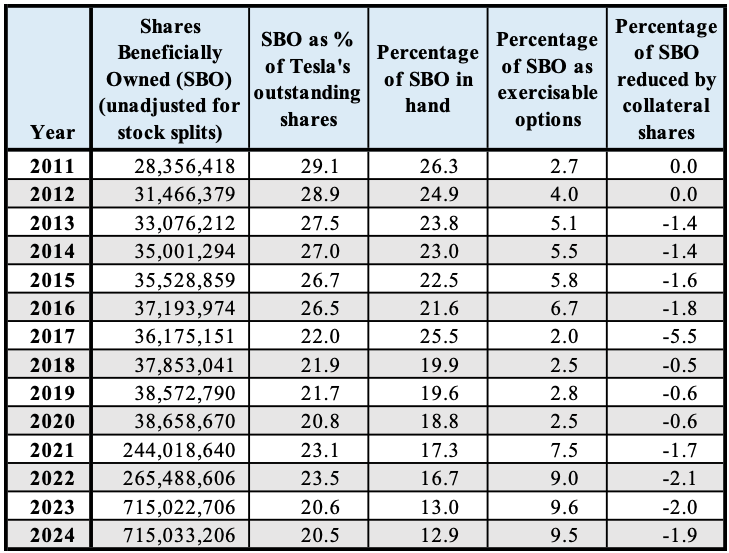

As shown in Table 2, as of March 31, 2024, shares beneficially owned (SBO) by Musk provided him with up to 20.5 percent voting power, with each share having one vote. This figure includes three different components. The first component is “shares in hand”, which Musk owns outright, acquired by his $315.8 million investment in Tesla plus shares retained after the exercise of stock options in 2016 and 2021. The second component is stock options that have vested and are therefore exercisable, but that Musk has chosen not to exercise thus far. Should Musk feel the need to increase his voting power to fend off a “takeover by dubious interests” (as he put it), he could immediately exercise these options, converting them to shares in hand. The third component is a deduction because of shares used as collateral for loans that could be called in at any time by the lenders.

Table 2: Elon Musk’s voting power from Tesla shares, 2011-2024

In 2011, Musk’s SBO in hand was 26.3 percent, declining to 12.9 percent in 2024. In 2017, however, SBO in hand increased to 25.5 percent from 21.6 percent the previous year. The change reflects Musk’s decision to exercise stock options, granted in 2009, and retain that portion of the shares that he did not need to sell to cover his tax bill. From 2021 to 2022, however, the percentage of SBO in hand declined from 17.3 percent to 16.7 percent, notwithstanding the exercise of options from the 2012 stock-option grant. That is because, around the same time, Musk was, quite exceptionally, selling 69.5 million shares valued at $34.1 billion to help fund his $44-billion purchase of Twitter.

Musk’s SBO as a percent of Tesla shares, however, increased by 2.7 percent from 2021 to 2022. This change resulted from 1) an increase of shares in hand of 9.6 percent when Musk exercised options from his 2012 stock-option grant, 2) a 6.5 percent increase in exercisable options under the 2018 stock-option grant as vesting targets were achieved, and 3) a reduction of shares in hand of 13.4 percent as a result of the sale of shares used to fund his acquisition of Twitter.

Musk’s 2018 stock-option grant, therefore, is critical to restoring the voting power that Musk lost by purchasing Twitter. With Musk’s vested stock options from his 2018 stock-option grant voided, he stood to lose 7.1 percent of his voting power. As is well known, Musk only thought once when he made his rash bid for Twitter. Given the importance that he places on control at Tesla, had he contemplated that in 2024 the Delaware Court of Chancery would rescind his 2018 option package, he might have thought twice about committing $44 billion to the purchase of another company.

Potential Challenges to Musk’s Control

On January 24, in Tesla’s Q4 2023 earnings call, Musk expressed concern that, under his watch, Tesla could implement an innovation strategy, “creating an artificial intelligence and robotics juggernaut of truly immense capability and power”, only to find himself voted out as CEO “by some sort of random shareholder advisory firm.” He continued (with our editing of redundant verbiage):

You know, we’ve had a lot of challenges with Institutional Shareholder Services, ISS—I call them ISIS—and Glass Lewis, you know, which there’s a lot of activists that basically infiltrate those organizations and have, you know, strange ideas about what should be done. So, I want to have enough to be influential—like, if we could do dual-class stock, that would be ideal. I’m not looking for additional economics; I just want to be an effective steward of very powerful technology. And the reason I just sort of roughly picked approximately 25% was that that’s not so much that I can control the company even if I go bonkers. And if I’m, like, mad, they can throw me out, but it’s enough that I have a strong influence. That’s what I’m aiming for is a strong influence but not control.

What is this system, apparently spearheaded by ISS and Glass Lewis, that has the power to mobilize shareholder votes against Musk and throw him out of office? We refer the reader to the book, Predatory Value Extraction, by William Lazonick and Jang-Sup Shin, in which they explain how, since the late 1980s, in the name of “maximizing shareholder value”, institutional changes in corporate governance have transformed the relations between hedge-fund activists and corporate executives to prioritize value extraction over value creation. The looting of the business corporation via distributions to shareholders in the form of stock buybacks, in addition to dividend payments, became the norm in the United States.

From its adoption in November 1982, Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Rule 10b-18 has given those who exercise strategic control over corporate resource allocation a license to loot the corporate treasury by means of open-market repurchases, aka stock buybacks. Then, during the 1980s, the compensation of senior corporate executives with stock options gave them the incentive, as value-extracting insiders, to participate in this looting process by executing buybacks. Meanwhile, large institutional shareholders became value-extracting enablers as their fund managers sought to exceed quarterly yield targets by placing a portion of their funds’ financial assets with hedge funds as value-extracting outsiders, who have an overwhelming penchant for stock buybacks.

In 1988, the U.S. Department of Labor issued what has become known as the “Avon letter,” which deemed it a fiduciary obligation for pension funds to vote the shares in their asset portfolios. In 2003, a ruling by the SEC extended this fiduciary obligation to mutual funds, thus making it much easier for a hedge-fund activist such as Carl Icahn, Daniel Loeb, Nelson Peltz, or Paul Singer, holding only a small percentage of a company’s shares outstanding purchased on the stock market, to line up a large block of proxy votes for board elections and thus pose a credible threat to incumbent management’s strategic control.

The activists can get help mobilizing proxy votes by soliciting the support of the two major proxy advisory services companies, ISS and Glass Lewis, which, as a consequence of the 2003 SEC ruling, emerged, unregulated, to dominate this specialized segment of the “market for corporate control”. The most important recommendations that the proxy advisors make to institutional shareholders concern candidates for election or re-election to the corporate board.

Meanwhile, in the 1990s, regulatory changes increased the tools available to hedge funds to attack incumbent corporate management, as well as the size of the “war chests” (to use Carl Icahn’s term) under hedge-fund management that finance the value-extracting campaigns. In 1992 and 1999, SEC amendments to its proxy regulations enabled hedge-fund managers to communicate freely among themselves and with corporate management concerning issues of corporate control. As a result, it became much easier for hedge funds to form de facto cartels—known as “wolf packs”—for activist campaigns.

The National Securities Markets Improvement Act (NSMIA) of 1996 enabled hedge funds and private-equity funds to avoid regulation under the Investment Company Act and Investment Advisers Act, both of 1940, even as NSMIA permitted the number of investors in a fund to exceed the former limit of 99. As a result, assets under management by unregulated hedge funds (and private-equity funds) soared from the late 1990s, augmenting the financial power of hedge-fund activists to engage in predatory value extraction while giving fund managers of pensions and university endowments, among other institutional shareholders, stakes in activist campaigns in their quest for higher yields on their financial-security portfolios.

Each of these regulatory changes has contributed to an institutional environment that empowers financial predators to challenge executives’ resource-allocation decisions, with devastating consequences for the U.S. economy. Consider the case of General Electric (GE), a once-iconic U.S. company that in 2011-2015 had been among the largest industrial share repurchasers, with $22.2 billion in stock buybacks (44 percent of net income) and $39.6 billion in dividends (another 79 percent of net income). On October 5, 2015, Nelson Peltz’s Trian Partners disclosed that the hedge fund had purchased $2.5 billion of GE’s stock—its largest-ever stake in a company but only about 0.9 percent of GE’s outstanding shares.

Not one cent of Trian’s $2.5 billion stake flowed into GE’s coffers for investment in productive capabilities or any other purpose. As a hedge-fund activist, Peltz epitomized the value-extracting outsider. The stated view of Peltz’s activist campaign was to pressure GE to increase its distributions to shareholders with a view to Trian selling its shares for a $2 billion profit in just two years.

Earlier in 2015, Trian had mounted a proxy fight at DuPont, with the backing of ISS, Glass Lewis, and the California State Teachers’ Retirement System. In the election of board members in May, incumbent management prevailed over Trian. Nevertheless, DuPont CEO Ellen Kullman warned that, as a result of the influence that Trian had gained during the proxy battle, Peltz would seek to establish a “shadow management” within DuPont to achieve his value-extracting objectives. Sure enough, on October 5, 2015—the very same day that Trian announced its attack on GE—Kullman resigned as DuPont CEO, with Trian-friendly board member Edward Breen taking her place.

When Peltz turned his activist attack on GE, no proxy contest was required. GE CEO Jeffrey Immelt and CFO Jeffrey Bornstein were quoted by the Wall Street Journal as being “completely aligned on the levers” suggested by Trian to get GE “from point A to point B”. Referring to Trian’s proposal to jack up GE’s stock price by doing large-scale stock buybacks, Immelt stated: “The repurchase opportunity is right in front of us.”

In 2016, GE distributed $8.8 million in dividends, just a shade under 100 percent of net income, plus $22.6 billion in buybacks, 256 percent of net income. In the first quarter of 2017, however, Peltz let it be known that he wanted CEO Immelt out, and by June Immelt announced that he was stepping down. In October 2017, Peltz got GE to put his son-in-law and Trian partner Edward Garden on the company’s board.

The adverse consequences for GE were drastic. From 2016 to 2021, GE’s revenues declined from $119.7 billion to $74.2 billion, and its worldwide employment from 295,000 to 168,000. Over the years 2017-2021, the company’s losses totaled $36.8 billion. In November 2021, GE announced that it would break itself into three companies, engaged in energy, medical equipment, and aviation—the industrial activities on which, beginning in the last decades of the 19thcentury, the company had been built. While Peltz had sold chunks of GE stock at different points in time, the company’s shares still represented about five percent of Trian’s portfolio, and Peltz and Garden pushed for the GE break up as a way of “creating” shareholder value for themselves.

Many of the largest and most successful U.S. business corporations do massive amounts of stock buybacks to keep hedge-fund activists at bay. Take, for example, the case of Apple, which from October 2012 through March 2024 spent $674 billion on buybacks (90 percent of net income) in addition to paying out $152 billion in dividends (another 20 percent of net income). Apple could have used a fraction of that vast sum wasted on buybacks to invest and exercise control over technologies that are critical to its final products.

Apple could have made a direct investment in a state-of-the-art semiconductor fab in the United States rather than helping first Samsung Electronics and then Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company become world leaders in advanced chip manufacturing by outsourcing its iPhone microprocessor fabrication to them. The same can be said about the rise of China-based CATL to its position as the world’s leading EV battery company, aided by Apple’s outsourcing of rechargeable battery manufacture for its ICT devices to CATL’s predecessor Amperex Technologies. Apple appears to have lost the capability to make direct investments in critical technologies when needed. Recently, the company has shut down its multibillion-dollar effort to develop autonomous electric vehicles, and it is a laggard in AI.

In our view, Apple’s obsessive focus on doing buybacks to manipulate its stock price has had deleterious effects on the strategy, organization, and finance required to build on its innovation in ICT devices. We have also argued that the only explanation for the decisions of Apple CEO Timothy Cook and his board (which includes Albert Gore Jr.) to throw away as much as $89 billion in one year, and an average of $59 billion per annum over 11.5 years, on stock buybacks has been to appease hedge-fund activists for the sake of keeping their jobs.

Does Cook’s strategy of looting Apple’s corporate treasury to insulate himself from hedge-fund activists foreshadow Musk’s fate at Tesla? In assessing his own vulnerability to an attack by a hedge-fund activist, Musk is undoubtedly watching the moves of Jeffrey Bezos, founder and chair of Amazon, who handed over the CEO position to Andrew Jassy in July 2021. Launched in 1994 with its IPO in 1997, Amazon, like Tesla, has one class of common shares with one vote each. In 1998, Bezos held 41 percent of Amazon’s shares outstanding, but that voting power declined to 20.7 percent in 2010 and 10.8 percent in 2024, diluted by share issues for stock-based pay, acquisitions, and sales by Bezos to fund his rocket company Blue Origin and opulent lifestyle. When Bezos and his wife MacKenzie Scott divorced in 2019, he retained the voting power of the 25 percent of his shareholdings in Amazon that she received.

Prior to 2022, Amazon, like Tesla, had done no distributions to shareholders, other than some share repurchases done between 2006 and 2012 as part of its plan to give one or two shares annually to low-paid warehouse and delivery employees. In early 2022, however, Amazon learned that hedge-fund activist Daniel Loeb was amassing shares in the company. In response, from January through May 2022, Amazon repurchased $6.0 billion in shares to boost its stock price and appease Loeb. In February 2022, Amazon announced a 20:1 stock split, designed to render a proxy attack more difficult for a hedge-fund activist such as Loeb by making its shares more affordable to small (retail) stock traders.

For the same purpose, Tesla did a 5:1 stock split in 2020 and a 3:1 stock split in 2022. During his campaign to save his stock options, before shareholders were finished casting their votes, Musk offered a prize tour of the Tesla factory in Austin, Texas with Chief Designer Franz Von Holzhausen to fifteen lucky shareholders. As votes were being cast, MuskX-posted that 90 percent of retail investors were in favor of re-approving his stock options. Following shareholder approval, Musk posted, “hot damn, I love you guys.” Retail shareholders at companies like Tesla can provide an important source of votes in the battle for corporate control as U.S. stock exchanges have become more powerful as value-extracting institutions.

Musk’s Options for Maintaining Control

You can bet that when Elon Musk makes a statement such as “there’s a lot of activists that basically infiltrate those organizations [i.e., ISS and Glass Lewis] and have, you know, strange ideas about what should be done”, he has in mind the scenarios that have played out at companies such as DuPont, GE, Apple, and Amazon, along with many others. His defense, as we have seen, is to amass as much voting power as possible, with his impetuosity in acquiring Twitter and (as it turned out) overreach in granting himself the initial 2018 stock-option package creating some self-imposed bumps in the road.

There are two other routes that Musk could have followed in his quest for unfettered strategic control at Tesla: issuing dual-class shares and taking the company private. For the former, he could look to the cases of Google and Facebook; for the latter to the case of Dell Computer. But exercising these strategic-control options (so to speak) would have been, for Tesla, far easier said than done.

In his X-post of January 15, 2024, quoted above, Musk lamented:

I would be fine with a dual class voting structure to achieve this, but am told it is impossible to achieve post-IPO in Delaware.

In its 2004 IPO, Google issued dual-class shares, with Class A shares, publicly traded on NASDAQ, having one vote each, and Class B shares, closely held by Google co-founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page, with 10 votes each. Google’s distributions of Class A shares to a broad base of its employees as stock-based compensation, however, eroded the majority voting power of Brin and Page, pushing it down toward 50 percent. In 2013, therefore, the company issued Class C shares with no votes, also publicly traded on NASDAQ, with holders of Class A shares receiving Class C shares as a stock dividend. In 2015, the company was renamed Alphabet, with Google as an operating division. By issuing Class C nonvoting shares to employees in their compensation packages, Brin and Page have been able to maintain majority voting control of Alphabet. On April 9, 2024, their combined voting power was 51.7 percent.

A condition for the creation of Class C shares imposed by Class A shareholders through litigation was that the company would be obliged to maintain the market value of C shares within one percent of the value of A shares or otherwise pay C shareholders the difference in cash or stock. A portion of the $224 billion in buybacks of Class C shares that Alphabet did from the fourth quarter of 2015 through the first quarter of 2024 was to manage this price differential by manipulating the price of C shares.

When Facebook did its IPO in 2012, it also issued dual-class shares, with Class B shares having ten times the votes of the publicly traded Class A shares. As of April 1, 2024, Facebook (now Meta) founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg owned 99.7 percent of the Class B shares, with 61.0 percent of total voting power. In 2013, Class B shares had possessed 67.2 percent of the voting power. Thus far, unlike Google, the issue of Class A shares for employee compensation and acquisitions has not pushed Class B share voting power anywhere near 50 percent.

Why didn’t Tesla issue dual-class shares when it did its IPO in 2010? When Google did its IPO in 2004, it was a profitable company with $3.2 billion in revenues, and when Facebook did its IPO in 2012, it was also profitable with $5.1 billion in revenues. By virtue of their social media products, both companies were already household names. Moreover, as software companies, their need to raise cash from the stock market for capital expenditures was much less than for a consumer-durable mass-production company such as Tesla. Their founders could do successful IPOs while maintaining majority voting power.

In Tesla’s case, the stock market would not have been willing to absorb an initial public offering of a loss-making company with only $117 million in revenues, ceding voting control to its founder/CEO through dual-class shares. If Tesla insiders had been willing to wait another decade or so to do Tesla’s IPO, Musk may have been able to realize his dream of dual-class shares. Instead, Tesla’s listing on the stock market without dual-class shares makes Musk vulnerable to a hedge-fund activist campaign.

As a publicly listed company, Tesla has been attacked by hedge-fund short sellers, bent on driving down the company’s stock price for their own profit. In 2018, Tesla was among the most shorted stocks ever. In frustration, at 12:48 PM on August 7, 2018, Musk tweeted “Am considering taking Tesla private at $420. Funding secured.” As a consequence of this tweet, the SEC charged Musk with securities fraud, and forced him to relinquish his chairmanship of Tesla for three years (thus far, Musk has not reclaimed it).

With that nine-word tweet, Musk effectively blew any chance he may have had to take Tesla private. He may have done better if he had consulted with Michael Dell about how to delist a company from the stock market for the purpose of securing control as a condition for investing in innovation—and then how to put it back on the stock market with dual-class shares.

Dell had founded the eponymous computer company in 1984 while he was an 18-year-old student at the University of Texas. A pioneer in selling computers over the Internet from 1996, by the first quarter of 2001 Dell Computer had a 12.8 percent share of the global PC market, surpassing Compaq as number one. Dell has been chairman of the company throughout its history and CEO except for 2004-2007. By that time, PCs had become a commodity business, and the company was doing large-scale buybacks—$27.6 billion, or 101 percent of profits, for the decade 2003-2012—to prop up its stock price. In addition, Dell paid its first dividend in 2012.

Rather than distribute corporate cash to shareholders, Michael Dell wanted to reinvest in more sophisticated technologies. To do so, he partnered with private-equity firm Silver Lake, to take the company off the stock market with a $24.9 billion tender offer, despite the opposition of Carl Icahn, who had snapped up six percent of Dell Computer’s shares. As a privately held company, in 2016 Dell spent $67 billion to acquire EMC, the leading data storage company, which was also majority owner of VMware, a cloud computing and virtualization company. With these acquisitions, Dell renamed the company he had founded 36 years earlier Dell Technologies.

In 2018, Dell Technologies listed its Class C shares on the New York Stock Exchange, and, with Michael Dell in control, has become a far stronger company, technologically and economically, than it had been before going private to reinvest in its growth. Dell Technologies has treble-class shares, with, as of May 1, 2024, Michael Dell possessing 69.3 percent of the voting power and Silver Lake Partners 17.4 percent. That is a control outcome that, for the foreseeable future, Musk can only fantasize about. Dream on, Elon.

Should Elon Musk be running Tesla?

In 2024, is Elon Musk the right person to be CEO of the world’s leading EV company? We respond to this question, not as shareholders, but rather as academic researchers concerned about the impact of his exercise of strategic control on Tesla’s ongoing contribution to the global EV transition. More pointedly, from the perspective of innovative enterprise, we ask whether Musk might abuse his power of strategic control.

There is no question that Musk has made a positive impact on the EV transition thus far, playing critical roles as a financial investor and a strategic decision-maker in Tesla’s success. Musk has carried out Tesla’s original “master plan” to produce a succession of high-quality and increasingly affordable EVs. His hands-on management style and presence on the shop floor have been important at crucial points in the development of the vehicles and the implementation of mass production. With Musk serving as chairman and CEO, Tesla survived its transition from startup to going concern, becoming the world leader in battery electric vehicles with its third-generation EVs, the Model 3 and Model Y. In overseeing these investments, Musk himself had his own “skin in the game” to the tune of well over $300 million.

Under Musk’s strategic control, Tesla recognized early on the critical need to invest in and deploy a coast-to-coast rapid charging network in the United States, which it subsequently expanded globally. As the first foreign-owned car company permitted to set up a wholly owned manufacturing plant in China, Tesla’s entry into the world’s largest car market helped accelerate the EV transition there. Tesla’s investment in manufacturing in Germany is helping to do the same in Europe. In collaboration with Japan-based Panasonic and China-based CATL, Tesla has enabled the manufacture of high-quality EV batteries at lower costs. Tesla’s innovation can claim credit for pioneering standard features in today’s EVs such as “over the air” software updates, large in-car displays, “self-driving” capabilities, and batteries that can power a car for several hundred miles on a single charge.

The future, however, may look very different than the past. There have been many examples of actions that Musk has taken that call into question his commitment to maintaining Tesla as an innovative enterprise. One is his decision to hold, simultaneously, the position of CEO at two other privately held companies that he controls, SpaceX, and x.AI, which may distract him from the challenge of keeping Tesla on the leading edge of innovation.

The most serious distraction thus far has been Musk’s acquisition of Twitter in October 2022. In acquiring Twitter, Musk sold Tesla shares worth $34 billion, reducing his Tesla voting power by 13.5 percent. Having taken strategic control of Twitter, Musk spent his first year laying off about 80 percent of its workforce. He has thus far diminished, rather than built up, the value of the company. Under Musk’s ownership, X, as he renamed Twitter, has seen its value fall from the purchase price of $44 billion to an estimated $12.5 billion.

As Musk focused on X, Tesla began showing signs of weakness, with declines in sales and profits recorded in the first quarter of 2024. In response to Tesla’s sagging numbers, Musk announced mass layoffs—more than 10 percent of the 140,000-person workforce. Musk had wanted to cut up to 20 percent, and 20,000 people have reportedly been given the pink slip. Several of Tesla’s top executives and managers have either left or have been fired.

After Tesla’s senior director of EV charging Rebecca Tinucci pushed back on Musk’s request to lay off a large proportion of her unit’s highly successful workforce, Musk responded by firing the entire supercharger team. This “bonkers” move, to use Musk’s own term, would seem to be grounds for throwing the self-anointed “Technoking” out.

Investment in a supercharger network has been, and remains, a key dimension of Tesla’s innovation strategy, and, at this stage of the EV transition, particularly in the United States, is critical to convincing potential buyers with “range anxiety” that they should purchase a battery EV—the only type of car that Tesla produces and sells. A certain amount of impetuosity might contribute to the creative process when a company is a crazy startup with a few hundred employees, but it can be a disaster at a large company such as Tesla, with over 140,000 people on its payroll.

Musk’s multi-CEO status can result in conflicts of interest that may not be resolved in Tesla’s favor. An example is the diversion of Nvidia AI chips to x.AI that were supposed to go to Tesla. Musk now faces a lawsuit from Tesla shareholders who claim that “Musk—CEO, controller, director, and ‘Technoking’ of Tesla—started X.AI Corp. (‘xAI’), a separate AI company, began diverting scarce talent and resources from Tesla to xAI, and raised billions of dollars for xAI while touting xAI’s access to Tesla’s AI-related data.”

Narcissism can be destructive as well. As we have seen, Musk has stated that he will not invest in Tesla’s AI and robotics capability if, through the proxy-voting system, he can be ousted as Tesla’s CEO. Even with the 2018 options package in force, Musk’s 20-percent voting power leaves him insecure. Moreover, the Delaware court may uphold the recission of his 2018 options package, which would reduce his voting power to a far more tenuous 13 percent.

Nevertheless, what Musk and his Tesla board have learned from the option-package vote on June 13 is that the vast majority of the holders of the company’s shares, not including those owned by Musk himself and his brother Kimbal, will support him—despite the contrary recommendations of ISS and Glass Lewis. This demonstration of loyalty should give hedge-fund activists—whom Musk rightly describes as “dubious interests”—pause in mounting a proxy contest. Then again, to keep the wolves at the door, Musk may take a cue from Apple CEO Cook and his board, and begin doing billions of dollars in stock buybacks, looting the treasury of Tesla for the sake of retaining his control.

What will Musk actually do? Will he allocate Tesla’s resources for the sake of an innovation strategy that can keep Tesla at the forefront of the EV transition? Or will he make good on his only lightly veiled threat to sabotage Tesla’s future to discourage a challenge to his strategic control by hedge-fund activists?

This conundrum speaks volumes about the perilous system of corporate governance that, in the grip of shareholder primacy, has caused the United States to lose global leadership in critical technologies while feeding massive income inequality. A CEO of a major industrial corporation must be focused on investment in innovation, which requires the CEO to exercise strategic control. The CEO’s motivation, however, cannot be control for its own sake but rather control as a social condition for investing in innovation.

It is not lost on us that Musk’s stock options aggravate the inequality present both within Tesla and, indeed, on the planet Earth. Musk’s recent behavior, however, also suggests an obsession with control over Tesla that supersedes his commitment to the EV transition. Notwithstanding his past contributions to that transition, his control over Tesla at this juncture appears to be more a problem than a solution.

Given his bully pulpit as Tesla CEO, however, we do have one suggestion of a way in which he can help maintain Tesla as a driving force in the EV transition. If Elon Musk feels that the prevailing proxy-voting system and hedge-fund activism are compromising his power to allocate Tesla’s resources to its innovation strategy, he might consider joining a movement to rid the U.S. industrial economy of its greatest disease: predatory value extraction.

Acknowledgements:

We are grateful to the Institute for New Economic Thinking and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research Program on Innovation, Equity & the Future of Prosperity for funding the research that underpins this article. Thomas Ferguson provided valuable comments on an earlier draft.

Endnote:

[1] Matt Hopkins and William Lazonick, “The Mismeasure of Mammon: Uses and Abuses of Executive Pay Data,” Institute for New Economic Thinking Working Paper No. 49, August 29, 2016; William Lazonick and Matt Hopkins, “Corporate executives are making way more money than anyone reports,” The Atlantic, September 15, 2016; William Lazonick and Matt Hopkins, “If the SEC Measured CEO Pay Packages Properly, They Would Look Even More Outrageous,” Harvard Business Review, December 22, 2016; William Lazonick and Matt Hopkins, “Comment on the Pay Ratio Disclosure Rule,” public comment to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, March 21, 2017.