A Time Traveler’s Legacy

Kindred

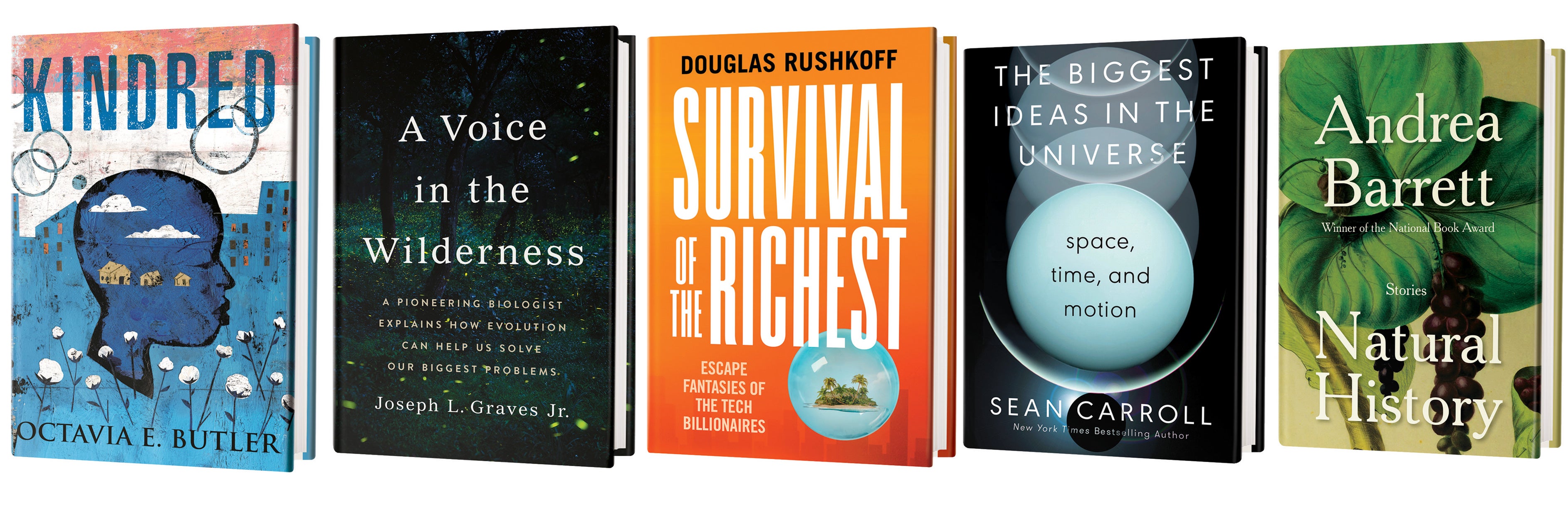

Octavia E. Butler

Gift edition. Beacon Press, 2022 ($27.95)

Afrofuturism—a global, multimedia genre of art rooted in Black cultures—is often used as a liberating lens through which we can reexamine our world. From tales told around fires in the dark, to the creation myths carved in ancient stones, to the visions contained in new technologies, this storytelling art is one of our oldest tools for making sense of an increasingly complex society. Afrofuturist writers explore a language of dreams and dystopias that expresses our greatest hopes while boldly confronting our darkest fears. They journey beyond colonial borders and timescales to reimagine old gods and traditional narratives, excavating the past to observe the rhythms of our present.

Among the most celebrated Black speculative-fiction writers is Afrofuturist pioneer Octavia E. Butler (June 22, 1947–February 24, 2006). Butler wrote meticulously plotted, science-based novels and short stories about shape-shifting immortals and psychic explorations. She excelled at exploring deeply uncomfortable things with unflinching clarity, particularly humanity’s hierarchical nature. Her choice of characterization, language and setting challenged notions of community and sexuality when set against the backdrop of competition for resources and survival.

As the first science-fiction author to be honored with a MacArthur “Genius Grant” and the first Black woman to win the Nebula Award and the Hugo Award, Butler created work that helps to frame Black women’s agency and aesthetics in a world that often denies the existence of both. When I was introduced to her work in college through her 1979 novel Kindred—arguably her most famous work, reissued this month as a special edition—it set my imagination on fire and changed my life path.

In Kindred, Butler skillfully retools the classic genre convention of time travel. The story follows 26-year-old Dana, a Black woman newly married to a white man named Kevin in 1970s California, who collapses time to face frightening ancestral legacies at the antebellum Maryland plantation where her family was enslaved. When Dana is dragged back in history as a lone traveler against her will, readers learn that she has a special connection to a redheaded child named Rufus.

Pulled from her comfortable California life, Dana must rely on more than contemporary knowledge and privilege. Through her journey, as well as Kevin’s separate one, readers witness how history is not static but a dynamic force that lives on in us. Tightly written in a way that refuses to romanticize the brutalities of the “peculiar institution,” Kindred revises long-held meanings of family, sacrifice and communal storytelling. The novel also reminds us that no one can defy time and live unscathed.

Kindred’s innovative take on time travel has been reflected in countless works and characters since its publication. Those include the 1991 film Brother Future, starring Moses Gunn, Carl Lumbly and Vonetta McGee; the Black supermodel of Haile Gerima’s classic 1993 film Sankofa; the 2020 horror film Antebellum; and Grammy-nominated singer Janelle Monáe’s 2022 debut story collection The Memory Librarian and Other Stories of Dirty Computer. Kindred’s influence is further seen in Walter Mosley’s 47, a young adult novel of slavery and time travel, and in Kiese Laymon’s Long Division. By creating characters who encounter profound difficulties but go on to become heroines and heroes of their own adventures, Butler redefined what a revolutionary looks like.

It’s an impressive footprint for a novel that was published 43 years ago, at a time when it was commonly believed that Black people didn’t read or write science fiction. Yet Butler was writing in a literary tradition that goes back nearly 165 years in English to the proto-science-fiction works of authors such as Martin R. Delany, Sutton E. Griggs, Charles W. Chesnutt, Pauline E. Hopkins and W.E.B. Du Bois.

Today her work continues to inspire a renaissance of Afrofuturism in its many forms. Her canonical influence is seen in the syllabi of universities across continents, in the graphic adaptations of her novels by Damian Duffy and John Jennings and in highly anticipated TV series and film adaptations of her books. Her presence lives in the stellar works of authors N. K. Jemisin, Andrea Hairston, Marlon James, Maurice Broaddus, Ibi Zoboi, and others.

Sixteen years after Butler’s death, her legacy of fierce imagination feels more relevant than ever. With Kindred illuminating so much of the most compelling speculative fiction, the book stands as an icon for recasting today’s challenges—envisioning new role models and possibilities in the process.—Sheree Renée Thomas

Sheree Renée Thomas is an award-winning fiction writer, poet and editor who lives in her hometown of Memphis, Tenn. She is co-editor of the upcoming anthology Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction (Tordotcom, November 2022).

Toward a Better Evolutionary Biology

An icon of genetics research: the fruit fly. Credit: nechaev-kon/Getty Images

A Voice in the Wilderness: A Pioneering Biologist Explains How Evolution Can Help Us Solve Our Biggest Problems

Joseph L. Graves Jr.

Basic Books, 2022 ($30)

A Voice in the Wilderness is not at all a traditional “my life in science” memoir because until very recently, that tradition—and that life—was nearly exclusively white. Author Joseph L. Graves, Jr., is not. Graves, in fact, is the first African American to earn a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology in the U.S., which he received from Wayne State University in 1988. His book, about evolutionary science as it is lived and practiced, offers a forceful narrative that is simultaneously autobiographical and scientific.

Graves refuses to mask the political and experiential realities of the U.S., authentically narrating a life wherein robust methodical and theoretical approaches in evolutionary biology can, and should, be entangled with the struggle for social justice. He confronts the culpability of evolutionary sciences in the construction of race and the horrific realities of racism while revealing an optimistic view of the redeeming antiracist promises of those very same sciences. He offers thoughtful insights into the messy dialogues of science and religion and the complicated history of evolutionary biology, covering the good, the bad and the ugly. And, to my great pleasure, he nods to the inspiration Star Trek gave him and so many other researchers who dreamed of science and adventure shaped by the necessity of equity and justice.

This is an engaging book with a lot of cool science—although it is never presented without context. The author introduces us to the always amazing Drosophila, the fruit fly at the center of much discovery in genetics research; dips into the mathematical and biological impacts of chaos with surprising clarity; and gracefully, carefully, navigates the relation between the biology of sex and gender.

When the voices of nonwhite scholars such as Graves share their experiences and practice of science, it helps to generate a future where evolutionary biology can become a better version of itself. For the many students in this field who do not look like the dominant faces in the textbooks and on the walls of famous museums and academic departments, getting glimpses of life intertwined with actual scientific engagement, oppression, assistance, failure and success provides a necessary invitation to be where they are, to push on, to make a difference. —Agustín Fuentes

Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires

by Douglas Rushkoff.

W. W. Norton, 2022 ($26.95)

Earth’s ultrarich have a plan for when the planet they’ve destroyed becomes uninhabitable: leaving it—and the rest of us—behind. In this brilliant and often horrifying analysis, media theory and digital economics professor Douglas Rushkoff explores the influence of what he calls “the Mindset,” a Silicon Valley–style fatalism that has billionaires believing that with enough capitalistic ambition and ruthless follow-through, they can escape their self-caused disaster. He exposes the Mindset as an antidemocratic, exploitative infection in society, arguing that our escape lies not in some island bunker or Mars mission but in institutional changes that reward interdependency over self-interest. —Michael Welch

The Biggest Ideas in the Universe: Space, Time, and Motion

by Sean Carroll.

Dutton, 2022 ($23)

Reading The Biggest Ideas in the Universe is like taking an introductory physics class with a star professor—but with all of the heady lectures and none of the tedious problem sets. Theoretical physicist and philosopher Sean Carroll levels up the standard popular-science book by explaining concepts such as mechanics and general relativity without dumbing them down—giving readers what he calls “the real stuff.” To STEM types, the result may feel like a more exciting version of requisite courses, but for those without the background, it might feel like a porthole into another world. —Maddie Bender

Natural History: Stories

by Andrea Barrett.

W. W. Norton, 2022 ($26.95)

National Book Award–winning writer Andrea Barrett’s graceful short story collection reenters the community of scientist characters (some fictional, some historical) she introduced in her 1996 debut, Ship Fever. In a New York State village in the late 1800s, Henrietta Atkins defies convention by choosing a teaching career and her work in the natural sciences over homemaking. Barrett’s interwoven stories examine Henrietta’s complicated choices, as well as those of her friends and relations, moving forward in time through characters’ shared experiences. Their friendships, scientific work and passions align and separate them in ways far more interesting than family ties alone. —Dana Dunham