For a proxy of how little media interest there is in the slow-moving public pension crisis, go to Twitter and search on “public pension underfunding”. The tweets I get, in year order, are 2016, 2020, 2020 2021, 2015, 2021, 2015. 2009, 2012, 2012.

No, sports fans, the lack of current intereest is not because the problem has gotten better. With the Fed trying not merely to whip inflation but also to get the US on a lasting basis out o a ZIRP-y policy regime, the outlook for financial assets for the next foreseeable while is not so hot. And that’s before getting to the impact of climate change and resource pressures on corporate profits. As we’ll discuss in more detail soon, a new Bloomberg op-ed by Aaron Brown, former MD and head of research at AQR shows that the state of public pension funding is more dire than most realize. For instance:

The widespread failure of the public pension model raises questions about the viability of the saving for retirement model. Neoliberalism demands labor mobility and weakens community ties. It also increases the burden on already fragile nuclear families. The retirement model in the era of subsistence farming was living with children and grandchildren or other extended family members. Oldsters could still be helpful even if they were secondary players in providing for household needs, by child care, light cooking and cleaning, and other support. In the post World War II era, the corporate and labor elite got generous pensions, while others could still save for retirement by buying a house. 30 year mortgage terms matched the usual working lie. A retiree could live mortgage free or sell his house and move into a smaller abode.

Short job tenures, pricey housing leading to much later initial home purchases, and howeowners being encouraged to extract equity via tax-advantaged second mortgages have undermined the “home as savings vehicle model.” Now individuals are exhorted to save and invest in financial markets.

But market touts forget that the stock market took until the mid 1950s to recover from the 1929 crash. And the post World War II period was exceptional, with the US initially at 50% of global GDP able to implement governance structure of its liking and under its thumb. After the stagflationary 1970s, the US then had a very long run of falling policy interest rates that ended in May 2007. Declining interest rates boost financial asset prices, particularly of typically-levered assets like real estate and risky assets like stocks. Asset prices got another lease on life with the Fed and other central banks driving and keeping interest rates in negative real yield territory.

The problem is that investing for retirement has pretty much nada to do with productive investment. Secondary market securities trading is a tiny fraction of new security sales to fund company operations. One tell of how little public companies do in the way of investing in their businesses is their level of stock buybacks. We pointed out in 2005 how companies had become so short term oriented that they were unwilling to pony up even for projects with one year paybacks, fearful of the impact of higher expenses on the next quarter’s earnings. That means many executives have deemed the most attractive path to be slow-motion liquidation via using cost cuts as their main engine for profit growth from existing operations.

The reason that public pensions are part of this problem is that public pensions executives and trustees, like many individual investors, were encouraged to think long-term investment returns of 7% were entirely reasonable. But it’s not reasonable to expect investments to keep returning more than GDP growth. The indirect proof of that fallacy is the degree to which investments, as in capital, has engaged more and more rentier activities to the detriment of labor. In the US, profits as a share of GDP were roughly 6%, a level Warren Buffett deemed to be unsustainably high. In the last few years, profits compared to GDP have risen by nearly 2x. So increased labor crushing as a tailwind to stock prices is also likely on the wane.

Mind you, not all public pension funds are in bad shape. Brown’s data looks particularly dire compared to other overviews, but those typically look only at state pension plans, while he includes municipal plans. From his piece:

State and local pension funding is one of those perennial crises that always seem to loom but only occasionally produce limited actual disasters in places like Detroit, Puerto Rico or the smaller but more recent Chester, Pennsylvania. Essentially all 21st-century municipal bankruptcies in the US are due to underfunded pension plans. But none of the defaults so far have led to falling dominoes: soaring municipal bond yields, taxpayer revolts or general government employee strikes. Will state and local pensions stagger along for the next few decades, bankrupting the odd declining city or three but not triggering a general political or economic crisis? Or are we, in Jim Steinman’s immortal words, “living in a powder keg and giving off sparks”?

Note that one reason the day of reckoning seems slow to arrive is that pensioners in defined benefit plans, thanks to recent appellate and Supreme Court rulings, cannot sue plan sponsors or trustees for breach of fiduciary duty and other misconduct until, literally, they don’t get their full benefits. The fund has to be so depleted that it can’t make mandated payments before the beneficiaries have standing. This is completely different than defined contributions land, where a reduction in beneficiary balances that can be attributed to fund manager bad acts does confer standing.

In addition to the entire “invest to retire” scheme being questionable, many public pensions have self-inflicted wounds. Christine Todd Whitman, as New Jersey governor in the early 1990s, started the vogue of deliberate underfunding, based on the barmy idea that fancy market footwork would fill any shortfall. New Jersey has been rewarded with one of the most underfunded systems in the US.

Brown notes that public pensions as a whole have made the big mistake of cutting contributions when the stock market was strong; CalPERS declared a contribution holiday during the dot-com era. Again from Brown:

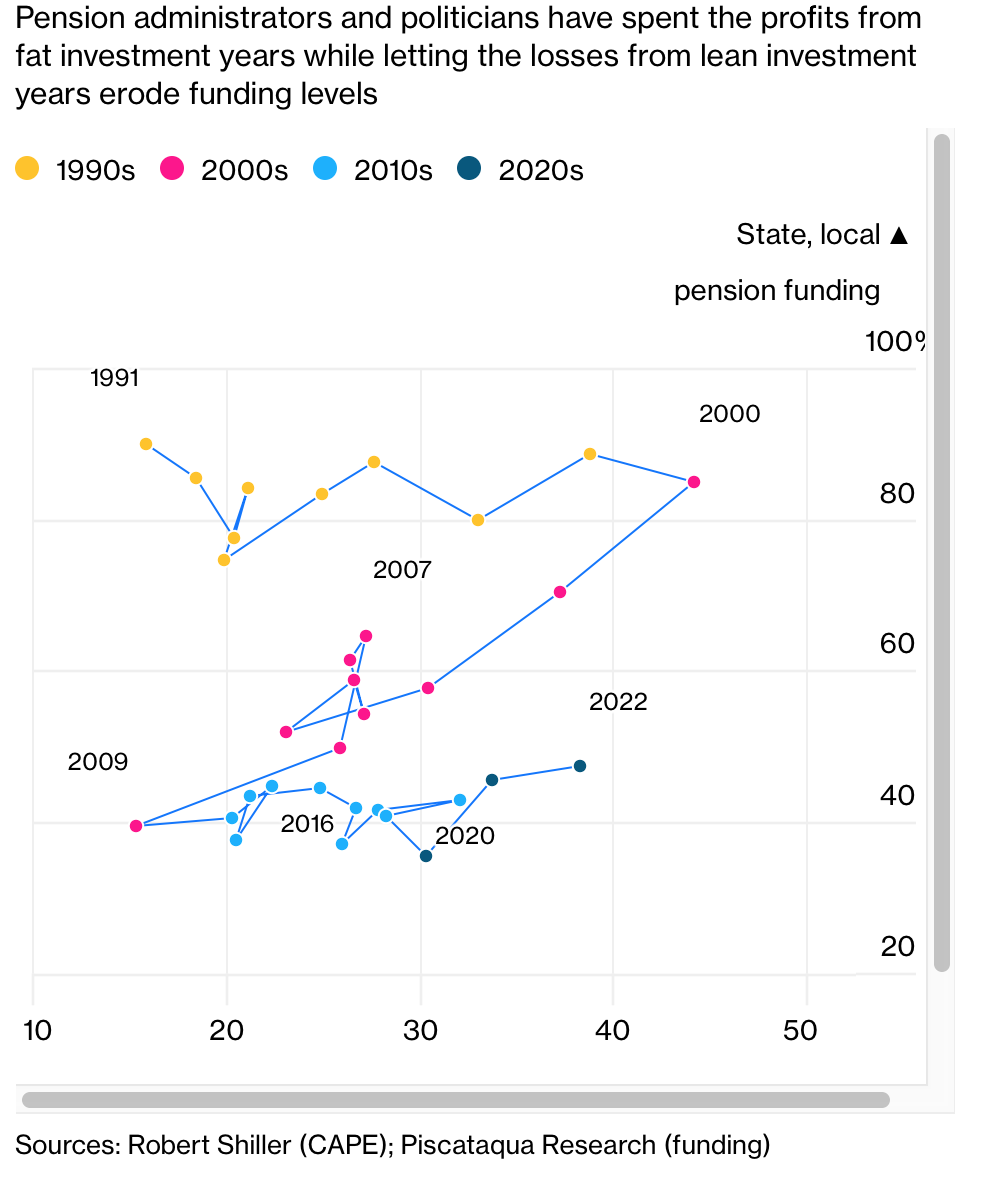

I think we can get more insight by looking at what engineers call a “phase space.” Instead of graphing the funding levels over time, let’s look at them compared with cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratios (CAPE). This is a measure developed by Yale professor Robert Shiller that divides current stock prices by average inflation-adjusted earnings over the past 10 years. I consider it the best standard version of price-earnings ratio….

Admittedly, phase-space diagrams take a bit more work to understand than time series charts, but I think this one rewards the effort. You can see from 1991 to 2000, stock valuations nearly tripled, while pension funding levels did not change much. One is reminded of the bumper sticker seen in Silicon Valley in 2000, “Lord, give me another internet boom, I promise not to waste it” (recycled from the 1980s-era oil boom sticker). State and local pension administrators and politicians wasted the internet boom by using rising stock prices and low interest rates to cut pension funding and increase promised benefits. They did not increase reserves as CAPEs soared to 44.20, far above the 1929 peak value of 32.56, strong reason to expect either a stock crash or a decade of mediocre real returns.

Over the next decade, as CAPEs fell back to 1991 levels, pension funding fell with stock markets. There was a brief reversal during the 2003-06 housing bubble — fund administrators did not waste that one — but the subsequent housing crash and economic crisis wiped out those gains and continued the downward trajectory.

Next came the longest bull market in history from 2009 to 2022 and, like the 1990s bubble, it was wasted. Despite widespread reforms to cut benefits and increase contributions by newly hired workers, an increase in government contributions and adoption of increasingly aggressive investment strategies, February 2023 aggregate funding levels are probably similar to 2009 lows.

This is three decades of history to argue that state and local pension administrators and politicians will spend the profits from fat investment years while letting the losses from lean investment years erode funding levels. When valuations rise, they’re treated as permanent economic gains. When they drop, they’re treated as temporary mark-to-market losses that don’t affect long-term economic fundamentals. If that continues, disaster is certain whether future investment returns overall are better or worse than historical averages.

Note that Brown has not included out pet hobbyhorse, that public pension funds increasing their allocations to supposedly higher-returning “alts,” as in alternative investments like private equity, has worsened returns compared to simpler and cheaper strategies for virtually all public pension funds and endowments. And CalPERS is one of the biggest sinners, as in biggest generators of “negative alpha”.

This sorry tale reinforces the idea that pension should primarily be a Federal responsibility. The US creates its own currency and can always afford the spending. And if we had more rational leadership, stronger pension rights ought to produce more growth-oriented spending policies. None other that arch neoliberal Larry Summers has pointed out that infrastructure spending can be expected to generate $3 in GDP for every dollar of expenditure. How about having an economic think tank rank order spending in terms of growth payoff. Funny we don’t see analyses like that as a matter of course.

Similarly, if we had better leaders, we might also see more in the way of programs to deliver services to retirees more efficiently. One reader described how social workers visit the homes of elderly people twice a week, bringing even portable bathtubs, to bathe them as well as shop and perform other tasks to help keep them living independently. But now that nursing homes are big business in America, we could never get there from here.

Sadly, as with our foreign policy, it looks like on the public pension front that we’ll have to see real breakdown before we get real change.