KY ANH DISTRICT, Ha Tinh Province, Vietnam – On a spring evening at the end of January, Ha Huy My received the phone call his family had been waiting for.

A few days before, local officials had contacted him looking for information about his uncle, who had died in 1967 in the war.

At his family home, nestled beneath its red tile roof among a village of blue and green houses by the sparkling sea, Huy My wondered: Why are they asking? About his uncle who had gone to war and died so long ago, a man named Cao Van Tuat, a man he never really knew?

Then, a short time later, he heard a rumor about a fallen soldier’s diary that had been found by an American veteran.

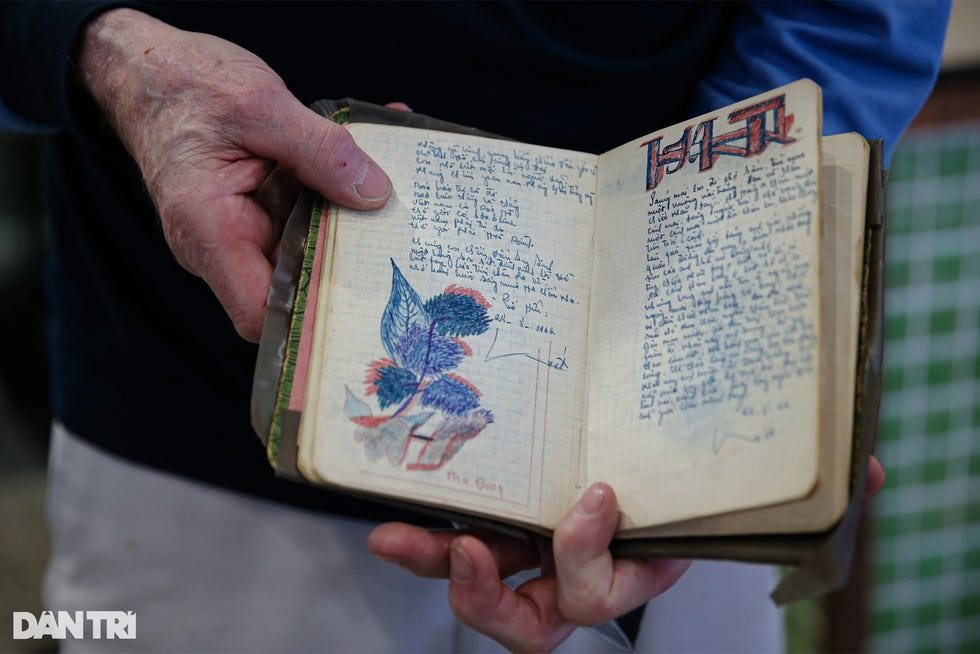

The diary was elegant, apparently, with poetry and drawings etched amid the entries. The American soldier had found it on a battlefield. For his job, for wartime strategy, the thing to do would have been to hand it over to military intelligence. But the book was too beautiful to hand over.

So he had kept it, hidden away, for more than 50 years. In the space of so much time, the American vet had come to realize the book was not too beautiful to hand over. It was too beautiful to keep.

The American was a man named Peter Mathews. He had no idea who had written the diary. But he wanted to find that Vietnamese soldier’s family and give it back.

At first, Huy My couldn’t imagine how he was involved. He had been only 2 years old when his uncle left for the war and never came back.

“I personally did not know his handwriting,” Huy My said. He had never even seen his uncle’s picture.

Even as he started to realize why local officials had called him, Huy My was unsure.

The book was reportedly filled with poems by renowned Vietnamese poets like Te Hanh and To Huu, which Huy My assumed his uncle had not had the chance to study in school before he left for war.

The worst thing, he thought, would be to take this diary as his uncle’s and be mistaken.

“It would be a tremendous sin and guilt had the diary belonged to some family’s loved one,” he said. “We would be like robbing away their deceased member’s memento, a treasure to the family.”

But then, the official called and confirmed the names of the soldier’s parents – Huy My’s grandparents – and the soldier’s older sister – Huy My’s mother.

“That was when we were sure it was my uncle’s,” he said.

He poured cups of warm lid eugenia tea and sat down in his home. It was early March by now, and outside, the peach and apricot trees dotted the village with blossoms.

Huy My, a rice and soybean farmer, was more than 60 years old himself. Though he remembered almost nothing of the day his uncle left home in 1963, he knew that tomorrow would be a day just as important for his family.

The American veteran, Peter Mathews, was set to arrive. He would come to the village of Cao Thang. He would meet the family. He would be carrying Cao Van Tuat’s diary.

“Now,” Huy My said, “we just want to be able to touch it, to see it for ourselves.”

Peter, 1967

The four days of fighting came amid one of the longest and bloodiest battles of the Vietnam War.

Mathews, an Army sergeant with the 1st Cavalry Division, was sweeping through an area of South Vietnam’s Central Highlands near Dak To with his unit. In November 1967, they had flown in to help the 4th Infantry Division, which was engaged in the fight for a nearby airstrip.

They were preparing to leave when Mathews found the book.

The soldiers in his unit had been rifling through backpacks left at the bottom of a hill, known to the Americans as Hill 724, named for its elevation above sea level.

North Vietnamese soldiers would often drop their backpacks in a staging area rather than carrying the heavy packs up a hill while fighting, Mathews said.

Mathews’ pale blue eyes scanned the stash left on the ground. His team’s job was to look for anything useful, any notes that could give them an inside look at battlefield plans.

Instead, wrapped in plastic, he found a work of art.

Mathews was struck by the elegance of the book’s pages, which were decorated with intricate drawings of flowers and landscapes and what appeared to be poetry, songs and journal entries.

He didn’t know what the handwritten words meant, but it looked as if the booklet was a personal diary, not a military document. Instead of handing it over to commanders, Mathews put it in his pocket.

And there it remained for much of the next month until his tour ended in December 1967.

“I just thought it was such a beautiful thing,” he recalled. “I was amazed by the detail, the artistic ability.

“Maybe I should have turned it in, but I just couldn’t part with it,” he said. “It didn’t look to me like military or secret information. I didn’t show it to anyone. I just put it in my pocket.”

Vietnam, 1967

Cao Van Tuat was 21 and living with his family in a small village in the province of Ha Tinh. His village lay beneath the distant mountains, on a small river near a sparkling sea.

His family earned a living growing rice and catching fish. They sent him to school, but by 1963, he was ready to fight.

The village and surrounding region had sent a flow of thousands of young people in North Vietnam heading to the southern front to fight the Americans in the war.

Ha Tinh, government reports show, sent 92,912 young men and women – more than 10% of the province’s population – and mobilized more than 330,000 civilians and 10,600 young volunteers in the war effort.

By the war’s end, 28,455 of them would not return.

Tuat joined the North Vietnamese troops and left home in March 1963.

He left behind his parents, an older sister and two younger sisters. His family did not even have a photograph of him to hold on to.

The soldier sent one letter home shortly after he enlisted. It would be nine years later before they received his death certificate.

The story they had of the end of his life had no artwork, no poetry, nothing to remember him by.

“We did not know where he was, how his life was on the battlefield. We didn’t even know where he died,” Huy My said. “For the whole nine years before we heard of his death, our family was thinking, and wishing, he was alive. He did not send many letters. All communications were complicated and rare back then.”

All they knew from official records was that he had been killed, somewhere on the battlefield, in 1967.

Peter, 1967

In December 1967, about a month after he found the diary, Mathews returned to New Jersey. He wanted the war put behind him, so he tucked the diary away.

All the same problems he had when he left before the war were still there waiting for him, plus the new burdens he brought home.

Mathews had come to the United States from the Netherlands four years earlier, in 1963. He landed just a week before the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

He had lived in New Jersey and worked odd jobs for a few years before he found someone willing to sponsor him for a green card.

Then, just months after getting the documentation, he had been drafted into the U.S. Army.

“When I was drafted I was young and stupid,” he said. “I was a young guy and I went along. I had to – they gave me the option to go home or go there.”

Mathews was a machine gunner during the war. He eventually became a squad leader in the 1st Cavalry, which was tasked with flying in to help other units if they needed backup.

Finally, in 1967, he came home.

By the time Mathews returned, “school was secondary,” he said. “I had to make a living.”

He applied for citizenship, thinking he was immediately eligible because of his military service, but he was denied because the Vietnam conflict was not a formally declared war. By the next summer, those rules had changed, and Mathews became a U.S. citizen.

He got married shortly after returning home, but that marriage lasted just four years, ending in divorce, he said, because of his drinking problems and depression.

He remarried, began a small construction business and focused on raising his four children.

The diary he had stuffed in his pocket on the battlefield now stayed in a box in his attic in Bergenfield, New Jersey.

But every once in a while, someone would come to visit, and he would pull the book out to let them see. People called it “the book from the enemy.”

Vietnam, 2023

Just a year after Tuat was killed, his youngest sister, who loved singing and dancing and was almost finished with school, died in a bombing.

As a strategic zone and a main traffic hub for troops and the flow of materials from the North to the Southern battlefields, as well as Lower Laos and Cambodia, the province of Ha Tinh was a prime target for American airstrikes. According to Vietnamese records, 200,000 tons of bombs were dropped on the province during the war.

One of those bombs fell as the 17-year-old girl was hanging out with friends after school. It tore off her legs, and she bled to death. At the time, in 1968, the family had not yet learned of Tuat’s death.

“Before she died, she was still thinking she could meet her brother at the other end of the war,” Huy My said. “It turned out they died just months apart.”

Tuat had a girlfriend from the same village, who is now in her 80s. They promised each other that after his return, his family would visit her house to ask for her hand.

“But it was wartime, I think few would hold out their hope,” Huy My said.

Huy My, the little boy whose uncle had gone away to war, had been the first grandchild in the family. As a child he lived with his grandmother, who gave him stories to remember.

“My aunts and uncle showered me with love,” he said. “My uncle, I was told, loved taking me out to the beach to play in the afternoons. He liked carrying me around on his back, roaming around the village.”

Huy My grew, and eventually he also went to war, in 1981 in Cambodia, fighting against the Pol Pot regime.

“At the time I thought of my uncle, of how he gave up his life for the peace of this country,” he said. “I wanted to follow his footsteps.”

Time passed and Huy My became a farmer like his family. He lived long enough that he has to pause to remember some things now. To remember how his family moved from the home where they lived by the beach then – it’s a seaside resort now. To remember the dates his other relatives have died.

But it’s his job to remember. As the family’s only son, Tuat would have traditionally been the one expected to continue the bloodline, take care of his parents as they got older, and after they died, care for their altar, a place in Vietnamese homes where families traditionally pay homage to their ancestors.

In Vietnamese culture, family members who die are honored at an altar with incense, prayers, flowers and other offerings.

Tuat’s family never learned where his body was buried. His sister’s family has cared for his altar since his death.

But in time, Tuat’s sisters grew older. As their health declined, Huy My had to take over. For the past seven years, he has been the one to honor his uncle.

On Lunar New Year this year, Huy My’s family, and families all across Vietnam, again lit incense at their altars and called to their relatives who had died. It was Jan. 22, 2023.

That day, as with each Lunar New Year, Huy My worried about who would eventually care for his uncle’s altar. The next generation would have no way to remember Tuat – not even a picture of him.

Four days later, on the other side of the world, a newspaper story appeared. In it was a man with pale blue eyes and a shock of silver hair, carefully cradling the yellowing pages of a diary.

Peter, 2023

More than a half century after he left Vietnam as a soldier, Mathews, now 77, was reminded of his time in the Army as he was working in a client’s home. He spotted a nón lá, a traditional conical straw Vietnamese hat, in the man’s home office.

The client had adopted two children from Vietnam and had visited the country several times. Mathews told him about the diary, and he offered to have one of his friends translate some of its pages.

Mathews began posting pages from the diary on social media, looking for more information in the hopes of one day returning the book to the soldier or his surviving relatives.

As he got some of the pages translated, to Mathews’ surprise, one of them held the soldier’s name and address.

Mathews’ social media posts seeking answers got him only so far. So he contacted a reporter in New Jersey. A story about his quest on northjersey.com caught the attention of a reporter in Vietnam.

Mathews already knew the idea of a lost soldier’s diary held a special place in Vietnamese popular imagination.

In 2005, a wartime diary found by an American soldier had become a sensation when it was published in Vietnam. The diary, published as “Last Night I Dreamed of Peace,” was a personal account of the war experiences of Dang Thuy Tram, a young doctor who cared for wounded Viet Cong and North Vietnamese soldiers before she was killed in 1970. It sold nearly half a million copies within a year and a half.

Peter had even made inquiries about getting this diary published, but they never seemed to go anywhere. A newspaper story, though, has a way of changing things.

When the Vietnamese reporter noticed the story about Mathews in 2023, he noticed the soldier’s home address was listed as in the province of Ha Tinh.

How the story began:He found an enemy soldier’s diary after a Vietnam War battle. Now he seeks its owner

Vietnam, 2023

When a Vietnamese reporter forwarded him information about an American newspaper story, Tran Nhat Tan, the provincial chairman of Ha Tinh, set about his work quickly.

Tan scoured records and called family members to verify dates and information gleaned from the diary’s pages.

The search for Tuat’s identity was complicated by just two small letters in a middle name. The book carried the name “Cao Xuan Tuat.” The file of soldiers from Ha Tinh listed an entry for “Cao Van Tuat.”

Records showed 36 soldiers from Ky Anh District with the last name Cao who had died in the war, nine with the name Tuat, and just one with both.

The names that the soldier had written of his father, mother, sister and hometown address were identical to the ones that Huy My had given. Another soldier from Ky Xuan commune who joined the army at the same time as Cao Van Tuat recognized the handwriting from a photo.

With that information, Tan and other local officials confirmed the diary’s author was Tuat and called his surviving relatives to give them the news.

This time Huy My knew that the rumors he had pushed out of his mind were true. The diary had belonged to his uncle.

His family would even be able to explain the confusion about the name. Tuat, at birth, had been given the common middle name Van. But like many people, he tired of his middle name and casually used another one. As an artist and poet, he chose Xuan, meaning “spring.”

Local officials soon arrived in Cao Thang, a quiet village that sits somehow untouched by the industrial development that has stormed much of Vietnam. They were there to see Huy My’s mother and aunt – Tuat’s sisters.

With them, they brought pictures of the pages from within the diary, their brother’s handwritten notes and drawings. When the two women saw the pages, they wept.

Peter, 2023

At home, Mathews held a diary that had been with him for 56 years. He understood it would not be his for long. Its next journey was already beginning.

Tan, the local official in Vietnam, had emailed the reporter in New Jersey and also asked Shannon Gramse, a writing professor at the University of Alaska Anchorage who had recently visited Ha Tinh as part of an educational exchange program, to help him connect with Mathews.

Within days, Mathews was flooded with requests from Vietnamese publications looking for interviews.

To accommodate the 12-hour time difference, he would give late-night interviews over Facebook Live. More than a dozen pieces were published in Vietnam, detailing the search for the soldier and his family’s emotional response to the book’s discovery.

Two weeks after the initial story broke, Mathews and his wife, Christine, were planning a trip to the country he had left 56 years ago as a young soldier.

Vietnam Airlines had offered to fly the couple from San Francisco to Vietnam. The journey would mean a long flight, then a shorter one, then a long drive, then a shorter one as local authorities would shuttle them closer. Their destination would be a village below the mountains, near the mouth of a small river, where blue and green houses cluster together by a sparkling sea.

Mathews would be going back to a country he had known only as a soldier, carrying the diary that belonged to the enemy, to give it to a family he had never met.

And he quietly made a promise.

He had shown the diary to people in the past, to friends and visitors who called it “the book from the enemy.” But now that he knew who wrote it, and knew to whose family it belonged, he promised himself that when he arrived in Vietnam, they would be the first ones to see it.

Becoming reality:Vietnam vet traces war diary author after amazing sleuthwork. Now he’ll visit the family

Vietnam, 2023

Tuat’s family waited.

They had spent six decades not knowing anything about the man they lost. Now, they would see his handwriting, his drawings, perhaps even his last thoughts.

“It’s like having him send us a message years after the war,” Huy My said.

Huy My sat, pouring tea, in his family home.

His mother, Tuat’s sister, was overjoyed at the news of the diary, he said, but because of difficulty walking after a stroke, she did not plan to attend the next day’s ceremony.

Instead, she looked forward to meeting Mathews at her home. It would be the first time “she ever sees an American in flesh,” Huy My said.

The family hopes information in the book will lead to the discovery of Tuat’s grave. Some of the book’s pages detail where the Tuat’s unit was stationed, and names of some of the people who were there.

Some of those soldiers are still alive, Tan said, and officials plan to meet with them to learn more.

Huy My said he was grateful to the veteran for keeping the diary safe and in good condition through so many years.

“Without him the diary would hardly make its way back home. Not a single drop of hatred or grudge we ever hold against him,” he said. “We lost our beloved uncle, but I understand it was war, and they were on different sides of the battlefield and had to shoot each other for their life.”

Outside, a thick layer of springtime haze hung over the village, obscuring the mountains beyond.

“It was war,” he said. “I used to be a soldier, so I know. People died when others survived.”

When the family sees the book and touches its pages, it will be like bringing a piece of his soul home, he said.

But that was not all. Now, even for a man with no photograph, there would be something to remember him by.

Though he had not yet touched his uncle’s diary, he had seen photos of its pages, and had transcribed some into a notebook of his own.

“He wrote for his mom, as if he knew his fate,” Huy My said. As if he did not expect she would see him again.

One passage had been written and dated the eve of the Lunar New Year. Families would have been gathering that night, but Tuat was writing in his diary without his family, far from home.

The nephew reached for his own copy and began to read aloud.

I am away from you, missing you a thousand times

Even though there are mountains and rivers between us

I could feel you are waiting for me in the middle of this cold night

…

I pray for your better health

Don’t yearn for my return.

Peter, 2023

It had already been a long trip, and Mathews hadn’t even reached his destination, when he emerged to face a wall of cameras.

There had been the 22-hour flight from the U.S. Then another two hours in the air to Vinh, a city near the coast, which was the closest airport to Tuat’s home village. Next would come car rides and ceremonies and handshakes.

But as soon as Mathews and his wife landed, the questions began. A dozen reporters and camera operators at the airport. More reporters waiting in the hallway of their hotel. A circle of other television crews a few steps away.

How do you feel getting back to Vietnam after nearly 60 years? they asked. Are you happy that you are about to meet the family of the diary’s owner? Do you still keep in touch with other veterans? What do they think of you returning to Vietnam to give back the diary? How did your wife help you with postwar PTSD? What is your wish for the future of the U.S. and Vietnam?

Mathews, sitting in a hotel armchair with a beer placed next to him, tried to answer them all without looking tired, and without making it a political event.

“I am not a politician,” he answered the last one. “I am not here for that. I am here on a humanitarian mission between myself and Vietnam.”

Then the reporters asked him to show the diary to the crowd and the cameras.

“No,” he said. “I had promised myself before, that as this notebook now is finally in Vietnam for the first time after 56 years, I want the family to be the first one to take a look at it and to touch it.”

Vietnam, 2023

Sunday morning arrived, and with it, crowds.

Since early morning, neighbors had come in and helped Huy My prepare a few pots of hot tea, dishes piled with peanuts and local peanut candies called Cu-do.

Outside, a crowd of neighbors gathered. Local authorities, traffic police and security amassed in the yard and spilled around the low concrete fence.

Mathews was being followed by a Vietnamese newspaper and at least two documentary crews. Other media outlets also followed his journey, some step by step.

When Mathews’ caravan arrived, it included leaders and officials from all levels in Ha Tinh, a doctor, along with the throngs of media and security. Curious locals pressed at the edges, their phones held high.

But really, there were just a few people he was there to see.

Mathews and his wife filed into the three-room home. Huy My stood with the couple by the altar, amid a loud buzzing noise, trying to show them the pictures of the deceased family members, and the one who was missing a photo.

Now, his diary would be there, they said, replacing the hollow space on the altar.

The men then held hands, and together stepped out to the yard to take a family picture with the lost soldier’s two sisters. Mathews sat next to the older sister, Cao Thi Dieu, who was in a wheelchair, trying to exchange words amid the frenzy.

Mathews and Huy My walked to the minibus parked at the gate waiting for them, still with cameras pointing at them from all angles, their hands squeezed tight together. The caravan zigzagged through rice paddies and acacia-covered hills to the communal hall for the ceremony to mark the diary’s return.

The building sits next to a memorial that honors members of local armed forces. It honors those who were killed in wars it calls the Anti-French and Anti-American Wars, and the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War.

Here, dozens of stone plates list the names of soldiers who died, with their dates of birth, enlistment and death. Nearly all of them were in their late teens or early 20s when they died. One of the names is Cao Van Tuat.

Inside the communal hall, the stage was draped with red and green curtains and decorated with a white bust of Ho Chi Minh, and his quotes addressed to Communist Party members written in yellow on red boards. On top of the display was a board: “Glorious Vietnamese Communist Party.”

Mathews walked in, a shock of silver hair in a blue and white shirt. His pale eyes surveyed the crowd, which included Vietnamese veterans who fought for the northern army.

“It’s been a long time, 56 years since I’ve been in Vietnam,” he said. “And last night I had several interviews with some of the TV crews, and I was very tired and feeling sick all the time. But just thinking about today, the tiredness was gone.”

The group was helped to the stage: Mathews and his wife. Huy My and his wife. And Cao Thi Nong, 78, Tuat’s younger sister.

Mathews shook Nong’s hand, and held it for a moment, before handing her the dark brown notebook.

She nodded a few times and tried to smile. Camera shutters burst all at once. Then, she was guided to a glass box prepared nearby. She placed the book on a red velvet tray inside.

The book had been with him since the war, Mathews said. When he would, on occasion, show it to people, they would call it “the book from the enemy,” he said, his voice breaking.

“But every time people said that, and I showed them the book, there’s this power of him that turns it around, and the word ‘enemy’ was not used anymore.

“The power of the book is that even the people who are skeptical and call it ‘the book from the enemy,’ every time they see the drawings and the writings, the word ‘enemy’ disappears.”