Yves here. Customarily, when publishing a cross post, your humble blogger provides additional and/or qualifying information at the top, and then the post second. Here we’ll provide Richard Murphy’s post first, and then add more tidbits from the IMF paper on inflation that he discusses.

Keep in mind that the IMF’s research wing is well to the left of its “programs” area and often publishes findings that are not friendly towards finance and mainstream economics.

By Richard Murphy, a chartered accountant and a political economist. He has been described by the Guardian newspaper as an “anti-poverty campaigner and tax expert”. He is Professor of Practice in International Political Economy at City University, London and Director of Tax Research UK. He is a non-executive director of Cambridge Econometrics. He is a member of the Progressive Economy Forum. Originally published at Tax Research UK

The IMF published a paper yesterday highlighting some of the impacts of inflation.

Some were totally predictable:

It will be no surprise to anyone that the biggest negative impacts of inflation are on those in the poorest groups in society and that relatively speaking those in higher-income groups do much better.

This is partly as a result of policy measures:

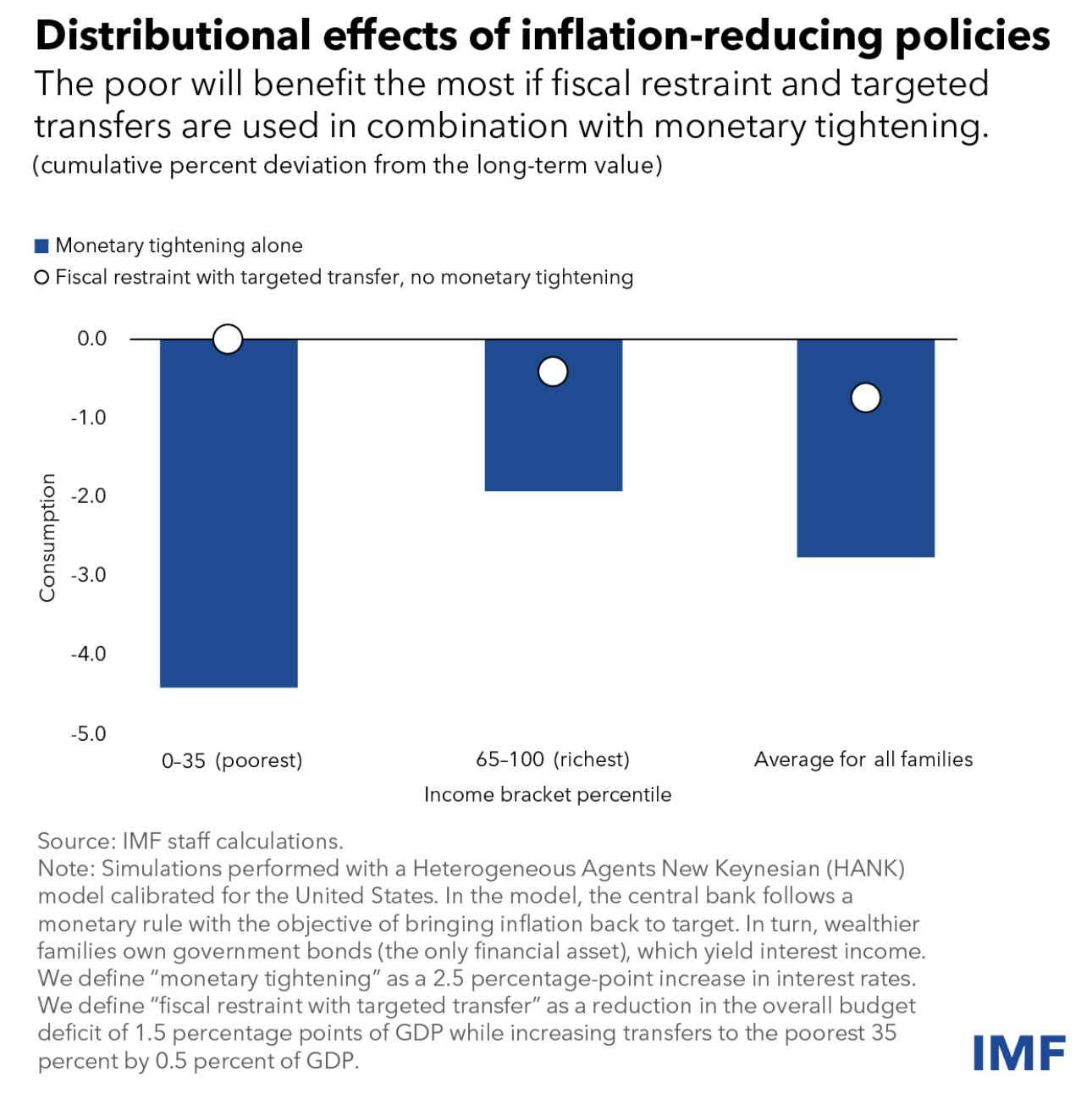

As the IMF notes, austerity combined with tight monetary policy hits the poorest hardest. There is no surprise there. Of course, this could be countered. As the IMF notes:

To safeguard the poor—who benefit more from public services—tax hikes or cuts in lower-priority spending must be combined with larger transfers. This strategy results, by design, in no drop in consumption for the poor, but also in a lower decline in overall consumption.

This is not happening sufficiently in the UK.

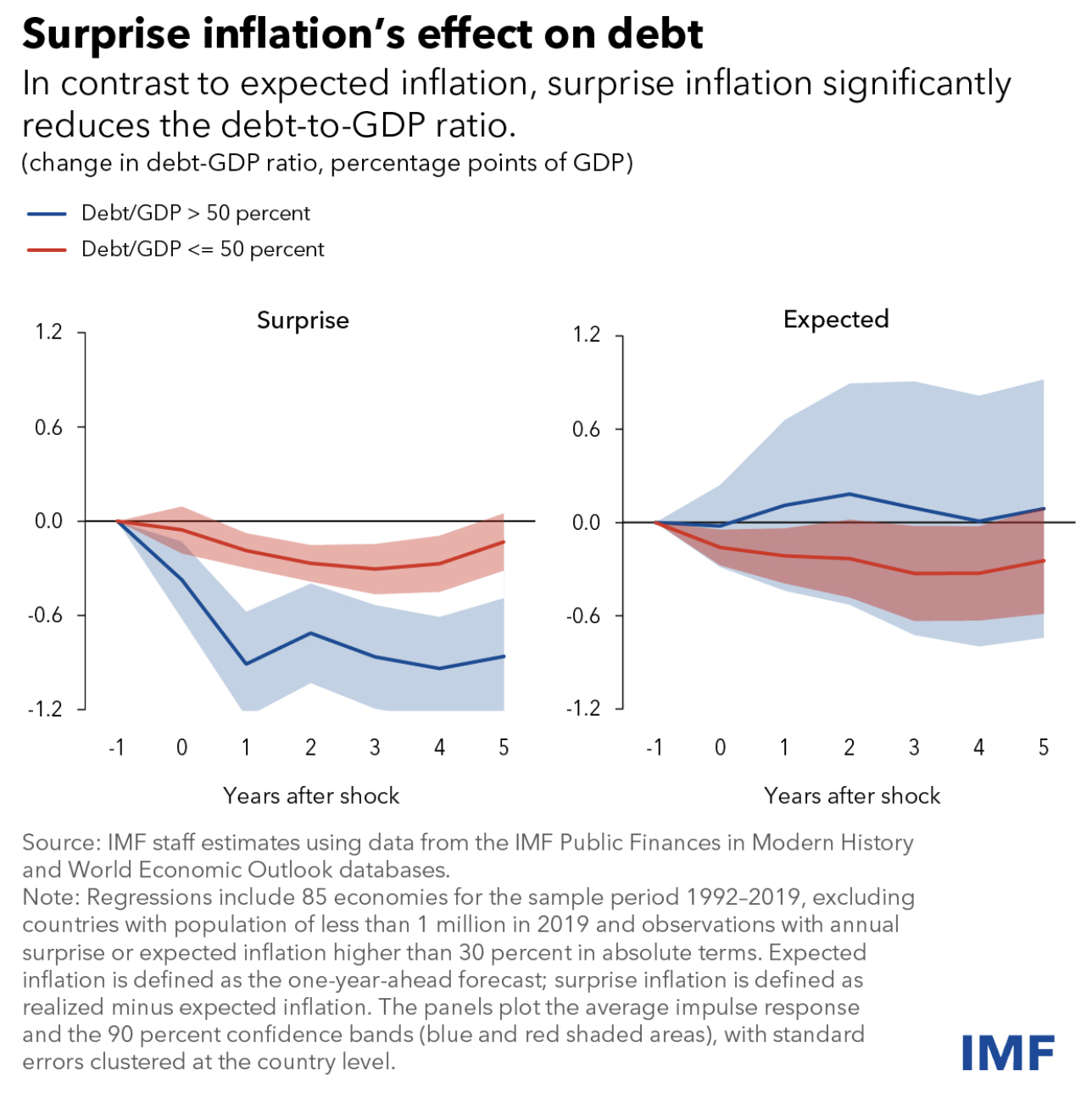

But there is what the IMF call a surprise outcome for governments:

Government debt-to-GDP ratios fall so long as inflation is constrained after breaking out. That is because the government wins at the expense of its bondholders, which s currently true. Of course, governments will claim this fall in debt-to-GDP ratios after inflation is a policy success. Actually, it is the result of their policy failure. In due course, that will need to be said.

As it will also need t be said that the gain should be spent to address the problems inflation has created, but you can be sure governments will ignore that.

______

Yves here. The IMF paper had another noteworthy section:

Although the impact varies across countries (and across income groups), the surveys reveal that:

- The faster rise in food prices compared to other prices hurt poor families disproportionately because food represents a higher share of their total consumption. This effect was most pronounced in low-income countries.

- Inflation eroded real incomes in commodity-importing countries, as wages across all income groups did not keep pace with prices.

- As inflation eroded the monetary value of assets and liabilities, families with negative net worth benefitted at the expense of creditors, particularly in countries with developed financial and credit markets.

- Redistributive wealth effects of inflation were also influenced by the age of the head of household: young families, which tend to be net borrowers, experienced gains through the wealth channels, whereas old households saw their wealth eroded.

This underscores a key point: that rises in inflation hurt lenders and benefit borrowers, which is why the capitalist classes are so insistent it be curbed quickly. It doesn’t hurt that central bankers’ preferred remedy is to increase unemployment and hurt workers.