Yves here. This post is written in a clinical manner, but it nevertheless attempts to assess the impact of the effort of the EU to divorce itself economically from the Russia. This looks to be a fair-minded effort, given the resistance to candor about sanctions blowback. For instance, it finds that Europe does not have ready substitutes for 3/4 of imports from Russia, mainly energy and “other critical and strategic raw materials.” Oopsie.

By Francesco Di Comite, Chief Economist team member, DG GROW (Internal market, industry, entrepreneurship and SMEs) European Commission and Paolo Pasimeni, Senior Associate Brussels School Of Governance – Vrije Universiteit Brussel; Deputy Chief Economist – DG Internal Market and Industry European Commission. Originally published at VoxEU

The European economy was still recovering from the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic when the Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered new economic disruptions, highlighting the importance of exposure to geopolitical risks and the vulnerability of international value chains. This column examines the exposures and dependencies of the EU economy at the time of the invasion and the massive adjustment taking place to decouple from Russia. While the openness and flexibility of the EU economy allowed businesses to reorganise their supply chains in a relatively short time, this adjustment may have structural impacts on the competitiveness of European industry.

The EU is one of the main actors in global trade and one of the driving forces of international value chains integration. This has allowed the European economy to reap the benefits of globalisation, specialise in high value-added processes, and increase its productive efficiency. Yet, a tension between efficiency and resilience has emerged in recent years. When in early 2022 the European economy was still recovering from the impact of the pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered new economic disruptions, highlighting the importance of exposure to geopolitical risks and the vulnerability of international value chains.

In this column, we analyse these vulnerabilities and focus on the endeavour of the European economy to decouple from Russia. In doing so, it complements a number of recent studies that have analysed the implications of the sanctions and post-invasion disruptions in Russia (Demertzis et al. 2022) and across the globe (Borin et al. 2022, Langot et al. 2022, Attinasi et al. 2022, Ruta 2022, OECD 2022, IMF 2022).

Decoupling from a structurally relevant trade partner requires multiple efforts. In a new paper (Di Comite and Pasimeni 2023), we illustrate the large ongoing adjustment that the European economy is going through, identifying exposures and the unwinding of dependencies in the course of 2022. We look at them from a risk-assessment perspective, focusing on dependencies and related vulnerabilities, especially on imported commodities.

The significance of Russia as a trade partner for the EU was amplified by the concentration of its input in key supply chains. Energy-producing commodities and other critical and strategic raw materials (CRSMs; see European Commission 2020, 2023) have a low degree of substitutability and a limited number of global suppliers. They account for more than three quarters of all EU imports from Russia. For the majority of these inputs, imports from Russia have been falling significantly in the course of the year, signalling a reconfiguration of supply chains towards alternative sources.

On the Russian side, the EU was the major trade partner, providing a vast variety of investment goods and high-tech products. The sectoral structure of trade suggests that China represents for Russia a possible alternative to the EU, because it is a major exporter in those sectors for which the EU was one the main partner for Russia. These are typically manufacturing of machinery and equipment, computer and electronics, fabricated metal and plastic products, chemicals and textiles.

Gross Trade flows

At the time of the invasion, the EU was highly exposed to the import of Russian commodities, notably fossil fuels and critical raw materials, but data show that it gradually managed to reduce such exposure over the course of 2022. Using a unique, high-frequency dataset based on customs data, we document a sudden and sizeable reduction of EU exports to Russia just after the invasion. Imports adjusted more gradually because of the low degree of substitutability of fossil fuels and critical raw materials. Moreover, they became much more expensive in the weeks after the invasion.

This has led to the EU accumulating an additional bilateral trade deficit vis-à-vis Russia of roughly €67 billion in 2022, compared with the same period in 2021. Such additional trade surplus for Russia corresponds to roughly 3.3% of its GDP and has probably been one of the factors behind the initial strengthening of its currency. Yet, with a sustained reduction in volumes of fossil fuel imports, by the end of 2022, the EU managed to stop, and even started to revert, this deficit accumulation vis-à-vis Russia.

Figure 1 Change in the EU–Russia trade balance with respect to 2021 (€ billion, five-week moving average)

Strategic Dependencies

In recent years, the European Commission has proposed methodologies to identify ‘strategic dependencies’ – products for which the EU relies on a highly concentrated set of foreign suppliers and has limited domestic production capacity (European Commission 2021, 2022) – and CSRMs – important commodities with a high supply risk (European Commission, 2020, 2023). We were able to identify 12 strategic dependencies vis-à-vis Russia (of at least €100 million in imports) and 19 CRSMs. With a few exceptions (nickel mattes and fuels for nuclear reactors), imports of products for which the EU had a dependency on Russia decreased significantly over the course of 2022, on average by 20 percentage points in market shares. The supply of 11 of the 19 CRSMs decreased by 50% or more.

Figure 2 EU dependencies on Russia: Market share changes between 2021 and 2022

Energy

Energy products, and fossil fuels in particular, were key inputs for the EU economy sourced from Russia (€110 billion in 2021, 74% of the total energy import). Pipeline gas imports alone account for more than one third of all EU energy imports from Russia, and in February 2022 they accounted for more than 30% of all EU gas inflows. Since today gas is the marginal source used to balance the internal energy system, its price evolution determines the prices of the entire EU energy and electricity systems.

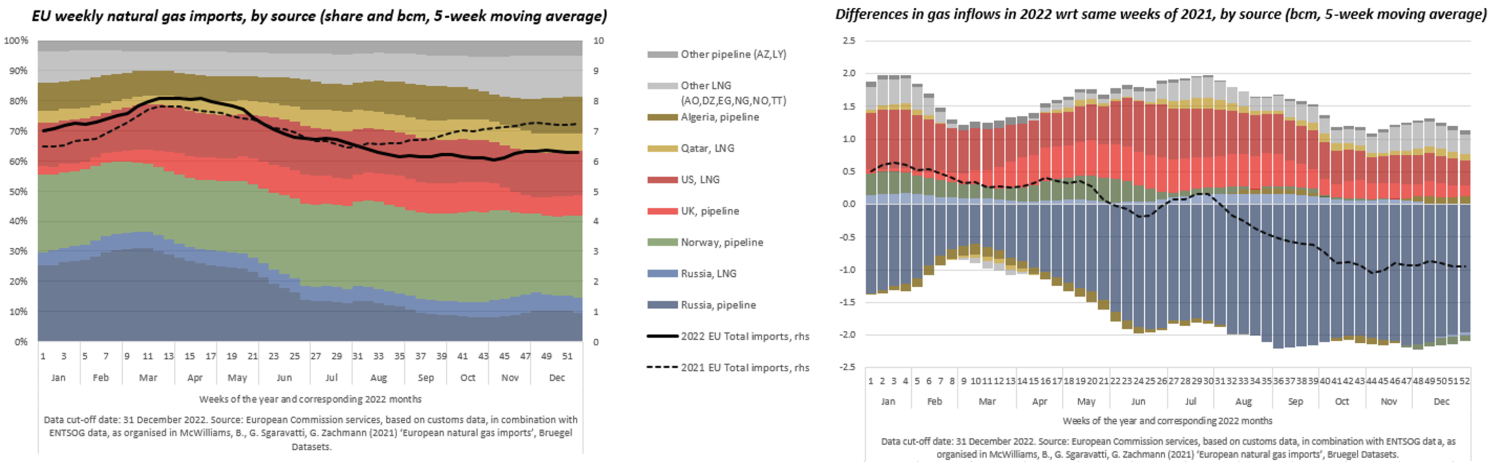

The total volume of pipeline gas import from Russia fell by one third in 2022 compared to 2021, whereas overall EU imports of gas in 2022 remained at roughly the same level, thanks to diversification into alternative sources of liquefied natural gas (LNG) – the US in particular. However, LNG import prices are 46% more expensive than pipeline gas import prices, with Russian LNG being the most expensive (Russian LNG import prices in the EU being 60% above average gas import prices) and US LNG being only slightly less expensive (50% above average gas import prices). A structural shift from pipeline to LNG gas sources may thus imply for the European industry a considerable loss of competitiveness.

Figure 3 Weekly natural gas flows (pipeline and LNG) into the EU by source in 2022 and 2022-2021 differentials

Conclusion

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has led to a permanent adjustment of EU supply chains, with a progressive decoupling from Russia. On the one hand, the Russian economy is gradually losing one of its main foreign sources of income. The extent to which Russia can substitute the EU with other trade partners remains an open question. On the other hand, the European economy is performing a sizeable adjustment in its supply chains, especially for key raw materials and energy products.

All in all, the European economy demonstrated substantial resilience to the shock. Our analysis shows that the openness and flexibility of the EU economy allowed businesses to reorganise their supply chains in a relatively short time. Yet, this adjustment can have structural impacts on the competitiveness of the European industry, given the need to turn to second-best supply chain configurations. If persistent, the relatively higher price of key inputs may result in losses of market shares, in particular in sectors key to the green transition.

The unprecedented nature of this shock has prompted a reflection in terms of resilience, of business models, and of supply chains that is not limited to short-term fixes. This crisis stress-tested the resilience and ability to adjust of the European economy. The challenge is now to ensure the sustainability and competitiveness of the emerging supply chain configurations.

See original post for references