Yves here. I’m taking the unusual step of publishing two not-too-long cross posts because the commonalities and differences in analysis and conclusions might be illuminating to readers. These two pieces, interestingly, suggest in the neoliberal and (press-wise) fiscally orthodox UK, quite a few informed commentators accept the proposition that this inflation was not created by too much spending but by two supply side shocks, first Covid disruptions, and second, Russia sanctions blowback. Europe and the UK have been more affected by the latter due to their greater dependence on cheap Russian energy.

Now you can argue that the US persisted in big time spending and excessive demand is a bigger perp here. There is a lot of commentary not founded on actual analysis touting that idea. The better analyses suggest that at most is still a secondary contributor; in the US, what is informally called greedflation, as in companies jacking up prices in excess of cost increases under the cover of inflation in other sectors, is an important but hard to quantify source too.

The first we are reproducing, that by Richard Murphy, correctly berates the idea that increasing interest rates is sound medicine for a primarily supply side inflation.

The second piece, by City A.M, which is a mouthpiece for conventional wisdom in finance circles in London, is almost schizophrenic. It goes on at some length to describe the drivers of the current inflation and government deficits do not feature prominent and even concedes in its opening bullet points that interest rate increase have not been very effective. But later on, it defaults to the incorrect view that central banks are the only line of defense. That may be true in practice, but that is due to legislators being unwilling to use tools they have, like strongly favoring countercyclical spending programs, and preferring to have unelected central bankers handle the inflation hot potato.

Note that Russia, after the war started, did a great deal of direct intervention in the economy to alleviate the shock of the loss European goods and services. The fast rebound suggest these targeted measures helped a lot. By contrast, the US sees focused initiatives like that as industrial policy, which is ever and always bad. And our approach to budgeting means the Administration has limited room to move. Nevertheless, the handwaving exercises when, for instance, the LA ports were bottlenecked were an embarrassing show of impotence. Even if this problem really was intractable on a short-term basis, former McKinzoid Pete Buttigieg needed to make a better show of fact-gathering as to why.

Murphy’s title is The present is unsustainable. Oil and banking have made it so. Something is going to have to change. The City A.M. title is What Really Caused The Inflation Crisis?. To Murphy first.

By Richard Murphy, a chartered accountant and a political economist. He has been described by the Guardian newspaper as an “anti-poverty campaigner and tax expert”. He is Professor of Practice in International Political Economy at City University, London and Director of Tax Research UK. He is a non-executive director of Cambridge Econometrics. He is a member of the Progressive Economy Forum. Originally published at Tax Research UK

The Bank of England meets this week to consider raising interest rates, yet again. The consensus of opinion is that they will do so by at least another quarter of a per cent. No doubt this will be accompanied by yet more calls for pay restraint because that is the only mantra that Andrew Bailey, the governor of the Bank of England, really knows.

There is no need for this increase in rates. This Guardian headline makes that clear:

Prices are falling, as was always expected to happen now, irrespective of interest rate rises.

What is more, pay continues to fall behind inflation, as this headline makes clear:

And what is the real cause of inflation? That is hiding in plain sight as these headlines from the FT and Guardian this morning make apparent:

It is profiteering that is driving inflation – with the government going all out to help by raising interest rates and maximising its support for big oil.

As I have already discussed this morning, climate policy is already creating one tipping point for politics in this country. A continuation of the current interest rate policy will create another. Things cannot continue as they are with politicians and big businesses laying waste to people’s lives without any apparent concern for the consequences. Something is going to have to change I feel: the present is unsustainable.

By Jack Barrett in CityAM.com, the online presence of City A.M., London’s first free daily business newspaper. Cross posted from OilPrice

- After pandemic disruptions and unusual goods spending, demand surged for essentials like energy, clashing with limited supply and leading to inflation.

- Significant events such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the impact on energy and food markets greatly affected inflation, leading central banks to respond with novel measures such as interest rate hikes.

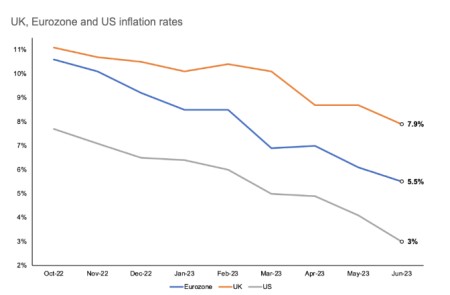

- Inflation rates remain above target in the US, Eurozone, and the UK, raising questions about their effectiveness and necessitating bold actions from politicians and business leaders to prevent future inflation spikes.

International supply chains were stretched by a combination of ports suddenly closing at short notice due to virus outbreaks, workers being forced to stay at home and unusually high goods spending overwhelming suppliers.

Once lockdowns ended and citizens gradually returned to normal spending habits, demand for essential items like energy came roaring back, colliding with strained supply.

Judging these trends to be “transitory”, as the Federal Reserve, ECB and Bank of England did at the time, can be seen as justifiable. Staff would eventually return from the pandemic. There was little reason to think spending wouldn’t rebalance. Oil, gas and electricity production would rise in response to higher prices.

The bigger concern for central banks was that they didn’t know what shape their respective economies would be in after two years of being ravaged by the pandemic, delaying the start to their tightening cycles.

That’s not to say interest rate rises weren’t required. Signalling an inflation intolerance to financial markets, households and businesses helps retain credibility. Quantitative easing probably lasted too long and was too generous.

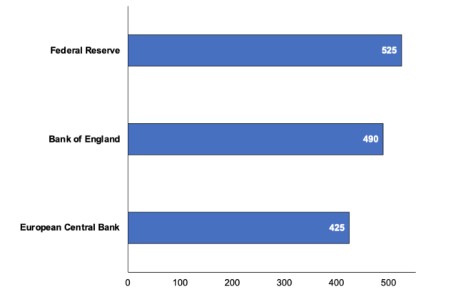

As such, the rate rises (finally) came. The Bank went first in December 2021, lifting borrowing costs to 0.25 per cent from 0.1 per cent. The Fed followed in March 2022, then the ECB fired its gun in July 2022.

Source: ONS, Eurostat, US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Everything changed in February 2022. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine could not have been foreseen. Its ramifications in energy and food markets were huge.

CPI in the UK jumped two percentage points in April to nine per cent. That was the biggest month on month annual increase since June 1979, according to modelled data from the Office for National Statistics.

In the US and eurozone, prices raced ahead. The dynamics required novel responses from central banks and they delivered. The Fed launched four 75 basis point rises. The ECB’s first increase was a smaller 50 basis points.

Those on Threadneedle Street were spurred into such action not by inflation but by the haphazard tax and spending decisions of Liz Truss during her premiership.

Kudos must be given to the Bank for its handling of that episode. It launched an emergency short-lived bond buying programme to hose down a fire in UK debt markets. Its 75 basis point increase went a way to tame higher inflation expectations.

Jerome Powell and co at the Fed have arguably been more aware of stimulative fiscal policy nudging up inflation. They went faster and steeper than their peers, partially to offset Americans pumping the up to $2,800 of parachute payments they received during the pandemic into the economy.

FOMC officials were also grappling with an inflation problem that was more demand driven, a factor that monetary policy is better at influencing.

Energy support packages were rolled out across Europe. France erected a more than €100bn support scheme, including capping prices. Germany doubled that gift. UK policymakers froze bills at £2,500.

Cumulative tightening by ECB, Fed and BoE

Source: ECB, Fed and BoE (basis points)

All these measures were designed to blunt the initial shock from soaring gas prices. They were necessary to avert a living standards catastrophe.

By partly shielding incomes, governments supported spending and inflation. The tension between monetary and fiscal policy was there for all to see.

So how have central banks done? Inflation is three per cent in the US (lower than Japan), 5.3 per cent in the Eurozone and 7.9 per cent in the UK – all above target.

Doubtless the Fed, ECB and Bank of England have had some of their credibility knocked. Those on Threadneedle Street should be regretful of their terrible forecasting record over the last 18 months.

Central banks, though, as economist Mohamed El-Erian puts it, aren’t the “only game in town”. They are simply inflation stabilising vehicles navigating the economic conditions handed to them. To prevent future inflation flare ups, politicians and business leaders must be bolder.

Investment needs jolting, Infrastructure renewed, better jobs created. Mere tweaks to interest rates will not cut it.