The Uncertainty Paradox

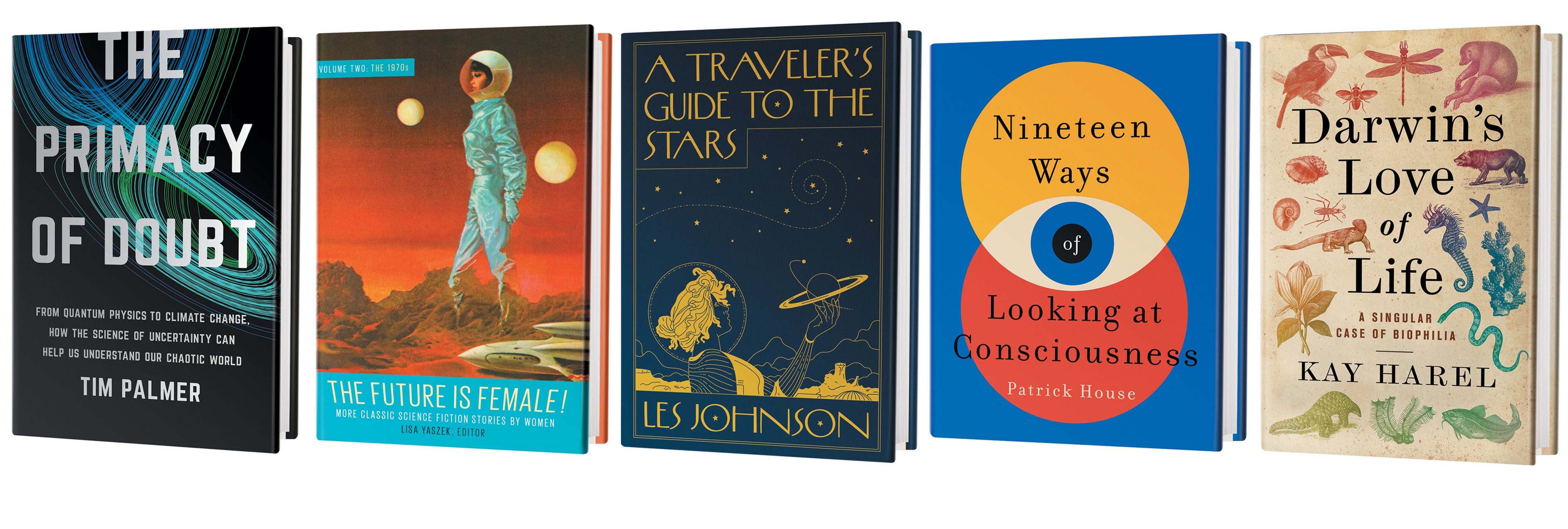

The Primacy of Doubt: From Quantum Physics to Climate Change, How the Science of Uncertainty Can Help Us Understand Our Chaotic World

by Tim Palmer

Basic Books, 2022 ($30)

Certainty is the currency of politics and social media, where boiling down complex issues into simple, bite-sized nuggets is now the norm. In his new book, The Primacy of Doubt, climate physicist Tim Palmer argues that the science of uncertainty is woefully underappreciated by the public even though it is central to nearly every field of research. Embracing uncertainty and harnessing “the science of chaos,” he says, could help us unlock new understandings of the world, from climate change to emerging diseases to the next economic crash.

The first section is a dense discussion of major questions and concepts in physics that illustrates how, among other things, systems can go from a stable state to a wildly chaotic one with little warning, but the book picks up speed when Palmer gets specific with accessible, everyday examples. The sharpest chapter is a crash course on how to predict the weather, a process Palmer helped to modernize. He explores the history of the forecast, starting with the first public storm warning in 1861 that used data from telegraphic stations from around the U.K. and taking us to ENIAC, the first programmable electronic computer.

Such efforts paved the way for the probabilistic forecasts used today, which predict the chance of rain in a given hour and provide the “cone of uncertainty” for hurricane tracks. This backstory puts our weather apps in a new light: if we required certainty to make choices, these tools wouldn’t exist.

Palmer is also a major contributor to improving climate models and is among the researchers who won the 2007 Nobel Prize for authoring the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports. His chapter on the topic, however, is a mixed bag. It excels in explaining evolving areas of research where reducing uncertainty is vital to figuring out just how bad things could get, such as whether clouds will speed up or slow down warming. Palmer proposes some interesting avenues for making the most of—and in some cases resolving—uncertainty, notably calling for a “CERN for climate change” that would focus on modeling how rising carbon dioxide and natural shifts in the climate will interact regionally over the next couple of decades (rather than globally over the course of the century). Doing so could help predict, for instance, long-term droughts in Africa’s Sahel region, giving governments and humanitarian agencies a head start to stave off famine.

But Palmer struggles to frame both the uncertainties of climate change and the severity of its effects. He tees up the chapter (subtitled “Catastrophe or Just Lukewarm?”) by defaulting to a both-sides approach: Are the “maximalists” right to suggest we’re in an emergency and should decarbonize as much and as quickly as possible, or are the “minimalists” right in suggesting that uncertainty is grounds for delaying action? The truth, he writes, is somewhere in the middle. Palmer notes that doubling atmospheric carbon dioxide alone would warm the planet by one degree Celsius. (That’s without factoring in feedback loops it might cause, such as the loss of ice cover or more water vapor in the atmosphere, which would further turn up the heat.) This is, he says, “perhaps not something to make a big deal of.”

But look at a planet that is already one degree warmer today than in preindustrial times, and the view is quite alarming. That incremental shift has fueled unprecedented heat waves on every continent, set the American West ablaze with ferocious intensity, and led to deadly deluges in areas that have never experienced such extreme back-to-back rainfall. Further, the most recent IPCC report, which Palmer urges his readers to reference, paints an increasingly dire picture that would seem to support a more maximalist view. Camille Parmesan, an ecologist at the University of Texas at Austin and one of the lead authors on that report, said in February 2022 that “we’re seeing adverse impacts are being much more widespread and being much more negative than expected in prior reports.”The Primacy of Doubt makes a compelling case for either reducing uncertainty or operating with confidence in the “reliability” of the uncertainty that remains. But it can obscure the much bigger picture of climate action. It’s impossible not to ponder how overlooking such nuances might sit with readers prowling for reasons to brush off the urgency of new climate policies.

Scientific American columnist Naomi Oreskes and historian of science Erik M. Conway’s book Merchants of Doubt, along with exhaustive journalistic and academic investigations, has shown how the fossil-fuel industry, conservative politicians and a tiny cadre of scientists have played up uncertainty with the intent to delay meaningful carbon regulation in the U.S. Palmer acknowledges this with a blithe neutrality, saying “we should be just as wary of inflation of uncertainty as of attempts to make predictions more certain than can be justified.” In doing so, he inadvertently brushes off the reality that uncertainty is too often used against society rather than to its benefit. —Brian Khan

Brian Kahn is an award-winning writer and editor. He is the climate editor at the tech site Protocol.

Radical Banality

By Wendy Pini. Copyright © 1975 by Warp Graphics, Inc. Reprinted by permission of Warp Graphics, Inc. From THE FUTURE IS FEMALE! Vol. 2. Copyright © 2023 by Library of America. Used by permission of the publisher.

The Future Is Female! Vol. 2: The 1970s: More Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women

by Lisa Yaszek

Library of America, 2022 ($27.95)

The first volume of Library of America’s “The Future Is Female” series collected science-fiction stories penned by women from the era of pulp fiction to the year of the moon landing. It closed with a knockout 1969 Ursula K. Le Guin story that dared to suggest our Space Age future might be an alienating drag. Le Guin’s “Nine Lives” digs into the loneliness of astronauts and clones alike, suggesting that advanced tech and interplanetary adventure could make actual human connection all the more rare. It imagined not just what the future might look like but how we might feel in it.

That framing doubles down in volume two, also edited by Lisa Yaszek, which finds women writing sci-fi in the 1970s blasting off on topics of sex, power, the banal routines of domestic life, and whether civilizations can ever achieve true equality. Whereas “Nine Lives” still centered on men and offered pulp thrills, the avowedly feminist stories here (including a Le Guin classic about the aged leader of an anarchist revolution looking back as her movement bears fruit) focus on women whose choices are circumscribed by societies that are pointedly like, or pointedly unlike, our own.

The results still jolt, 50 years later. Set in a 2021 where humanity is facing a dire overpopulation problem, Doris Piserchia’s “Pale Hands” is narrated by the cleaner of government masturbation stalls. Joanna Russ’s “When It Changed,” a Nebula Award winner, finds a planet where women have thrived without men for 30 generations suddenly reintroduced to what a newly arrived male astronaut calls “sexual equality.” (“Seals are harem animals,” he says, “and so are men.”) In the kickoff story, “Bitching It,” Sonya Dorman imagines the bored rutting of housewives in a world where women behave like alpha dogs in heat and men must passively take it.

Other works in this bold collection delve into the put-on hotness of what we now know as influencer culture, such as in the prescient “The Girl Who Was Plugged In,” by pseudonymous James Tiptree, Jr. Both Joan D. Vinge’s “View from a Height” and Cynthia Felice’s “No One Said Forever” detail everything a woman must give up to be free to embark on old-school adventures. And by dramatizing a sci-fi author’s effort to write a story that grows richer the more it draws from her own life, Eleanor Arnason’s “The Warlord of Saturn’s Moons” makes explicit these authors’ mission to claim the genre for impassioned self- expression. In their hands, the future’s not just female, it’s personal. —Alan Scherstuhl

A Traveler’s Guide to the Stars

by Les Johnson.

Princeton University Press, 2022 ($27.95)

What will it take to explore a distant star within 100 years? To illuminate the momentousness (and ethics) of sending humans light-years from home, NASA scientist Les Johnson helps us digest mind-boggling numbers—the distance between stars, the energy required to travel that far—while laying out the opportunities and limits of existing technologies. Whether we get there by solar sails or ion thrusters or nuclear bombs, the advances we make in pursuit of interstellar travel will likely also change the way we live on Earth. After all, we wouldn’t have electricity or cell phones “if our predecessors had not conducted science for the sake of science.” —Fionna M. D. Samuels

Nineteen Ways of Looking at Consciousness

by Patrick House.

St. Martin’s Press, 2022 ($26.99)

This book, thankfully, does not attempt to explain what consciousness is, how it arises, or why. Neuroscientist Patrick House instead sketches an outline for how we might look at who we are from the inside out through wittily rendered observations plucked from neuroscience, quantum mechanics, and beyond. Recurring examples—such as the curious case of a teenager’s laughter during brain surgery—provide a sense of the questions that might help us understand how our cells collectively conjure our selves. As befits a phenomenon that still evades a unifying theory, House’s collage forms a picture of our minds that is far more nuanced, and more perplexing, than the sum of its parts. —Sasha Warren

Darwin’s Love of Life: A Singular Case of Biophilia

by Kay Harel. Columbia University Press, 2022 ($26)

In these gentle but stirring essays, writer Kay Harel happily diagnoses Charles Darwin with “a singular case of biophilia,” or profound love of life, that engenders empathy, creativity and an intuitive sense of truth. Harel posits biophilia as the root of Darwin’s genius and the influence behind everything from his love of dogs and fascination with the insect-eating Drosera plant to his rejection of mind-body dualism and his sense that estimations of the earth’s age would one day align with the time span of evolution. Harel’s focus on the confluences of Darwin’s life rather than its conflicts offers a refreshing take on his legacy. —Dana Dunham