This deliciously-titled Financial Times story recaps a new study by Morgan Stanley equity strategists Edward Stanley and Matias Øvrum which provides a devastating takedown of the venture capital industry’s claim to making money for investors, as opposed to just themselves. The overarching finding is that venture capital funds typically don’t outperform stocks, and that’s before getting to the fact that it is pretty much impossible to pick venture capital winners (more on that shortly). Oh, and because venture capital is riskier than investing in equities, investors oughts to get better returns than if they just bought some index funds.

Mind you, this is hardly a new idea. The Economist pointed out some years ago, based on a different large-scale study, that venture capital funds only meet equity returns with a lot more fees and risks. Harvard professor Josh Lerner said as much in a 2015 presentation to CalPERS’ board, except he pointed out that to the extent the industry could claim to outperform, it was in the top 10% of the funds. Lerner insinuated that there might be a secret sauce for that; a one-time newbie on the HBS faculty had Lerner tell him how to get lucrative consulting gigs advising public pension funds on this Mission Impossible. As we wrote in 2014:

When you boil it down, this graph illustrates the ugly truth of investing in private equity: it’s not attractive unless you can outrun most of your peers investing in the asset class.

Rather than question the logic of investing in private equity at all, everyone in the industry has convinced themselves that it is reasonable to believe that they can be the Warren Buffett of private equity. The investment consultants go through the shooting-fish-in-a-barrel exercise of convincing their institutional clients that each of them is prettier, smarter, and more charming than average, and therefore capable of achieving sparking results. Needless to say, flattery is an easy sell…

Fundamentally, this is an intellectually dishonest exercise, and diametrically opposed to the way many public pension funds construct other parts of their investment portfolios. With public equity in particular, it’s almost certain that a significant majority of U.S. pension fund assets are invested in index funds. That’s because pension funds have recognized that, collectively, they cannot do better than average, and that after paying active management fees, actively managed public equity portfolios typically perform worse than the market average.

So it’s not as if these investors are so clueless that they can’t grasp the point that all of them cannot achieve above average results, let alone significantly above average results. Instead, with private equity, there is a desperate desire to be in the asset class for reasons that probably reflect a combination of intellectual capture by the PE managers, political corruption in legislatures that control public fund board appointees, and the need to have a strategy that could conceivably solve the pension underfunding problem over time.

Mind you, the “see if you can out-invest your competitors” problem is more acute in venture because outperformance is concentrated in so few funds.

Why are we belaboring this history before getting to a juicy paper? Because the bad facts about venture capital are, or should be, well known. But it’s just so much fun to talk to those venture capital mavens about all the great sexy things they invest in, even if the vulture, um, venture capitalists spend too much money finding and baby-sitting their charges, and most come a cropper anyhow.

Now to the Financial Times article. There is way too much good material to hoist it all. And the author often employs a delicious deadpan So please read it in full. Nevertheless, some key bits:

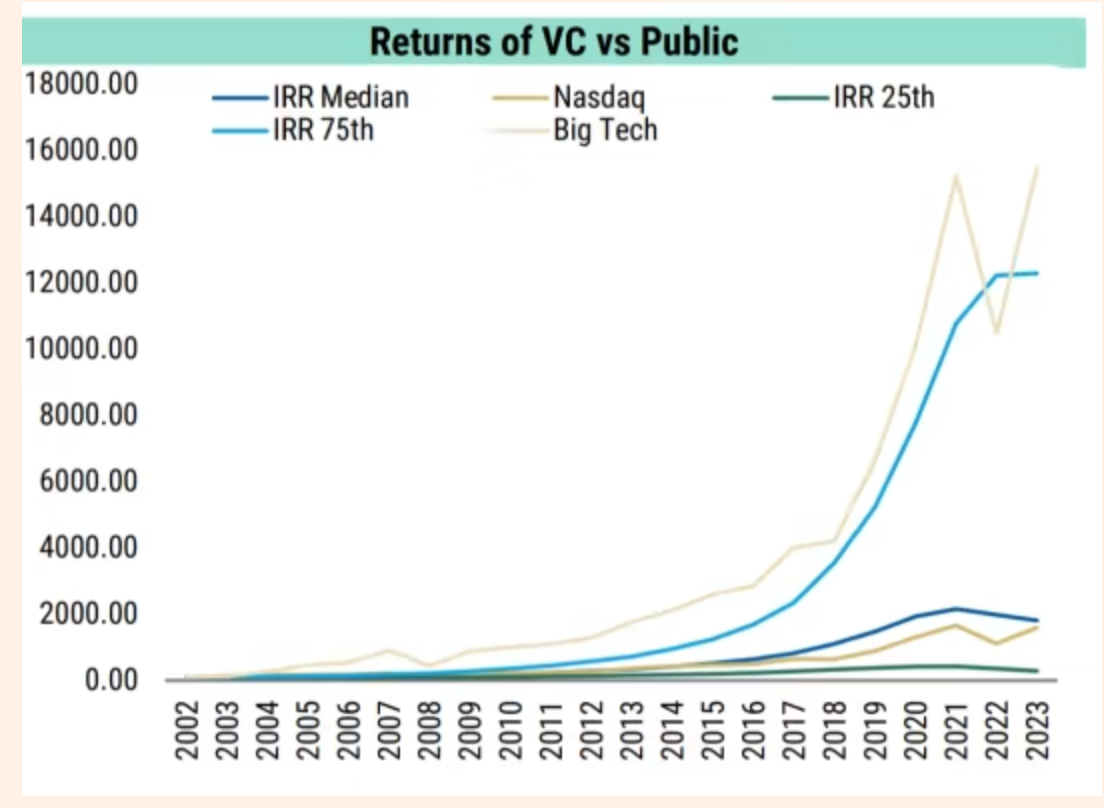

Morgan Stanley equity strategists Edward Stanley and Matias Øvrum have run the numbers for the past 20 years of crossover investing and found that the average VC fund doesn’t reliably outperform the average stock.

Any investor lucky enough to pick a top-performing VC was awarded with an internal rate of return “off the scale” relative to all other strategies, Morgan Stanley says. Mostly, though, the few big winners were funds that either backed tech giants pre float or caught 2021’s Spac boom…

Remove 2021 from the analysis and the top-tier gains would be more than 50 per cent lower, Morgan Stanley says. For the rest of the fund universe, even with the mid-pandemic exits included, the medium-term median returns have been no better than mediocre:

…And thanks to power law distribution of winners and losers, the worst VCs are impressively efficient at destroying wealth.

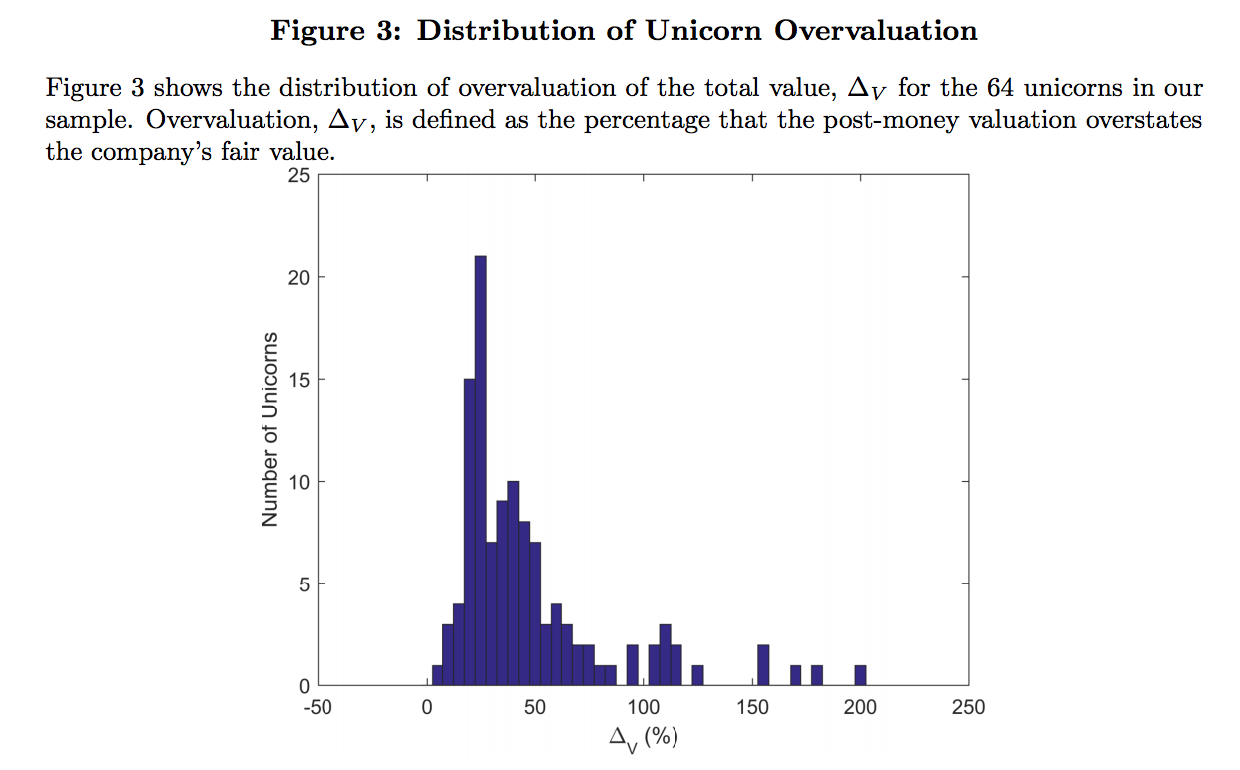

If you think that’s bad, this analysis, like virtually every one ever made of venture capital returns, does not allow for a pervasive practice that ought to be labelled a fraud. From our 2017 post, Fake Unicorns: Study Finds Average 49% Valuation Overstatement; Over Half Lose “Unicorn” Status When Corrected. The discussion is technical….because that’s usually how chicanery is executed in finance.

The key point to understand is that shares of venture capital companies are completely different than common shares of public stock. Each public share is fungible with other common shares. That is not at all the case in venture capital companies. Each round of fundraising has its own class of stock associated with it, with distinct rights and preferences. But these classes are not valued each by each to come up with a value of equity. Instead, the prevailing rule of thumb keys off the latest round…when the last investors in sucked value out of the earlier investors. From the post on unicorn inflation:

A recent paper by Will Gornall of the Sauder School of Business and Ilya A. Strebulaev of Stanford Business School, with the understated title Squaring Venture Capital Valuations with Reality, deflates the myth of the widely-touted tech “unicorn”….

Another deadly finding is peculiarly relegated to the detailed exposition: “All unicorns are overvalued”:

The average (median) post-money value of the unicorns in the sample is $3.5 billion ($1.6 billion), while the corresponding average (median) fair value implied by the model is only $2.7 billion ($1.1 billion). This results in a 48% (36%) overvaluation for the average (median) unicorn. Common shares even more overvalued, with the average (median) overvaluation of 55% (37%).

How can there be such a yawning chasm between venture capitalist hype and proper valuation?

By virtue of the financiers’ love for complexity, plus the fact that these companies have been private for so long, they don’t have “equity” in the way the business press or lay investors think of it, as in common stock and maybe some preferred stock. They have oodles of classes of equity with all kinds of idiosyncratic rights. From the paper:

VC-backed companies typically create a new class of equity every 12 to 24 months when they raise money…

Deciphering the financial structure of these companies is difficult for two reasons. First, the shares they issue are profoundly different from the debt, common stock, and preferred equity securities that are commonly traded in financial markets. Instead, investors in these companies are given convertible preferred shares that have both downside protection (via seniority) and upside potential (via an option to convert into common shares). Second, shares issued to investors differ substantially not just between companies but between the different financing rounds of a single company, with different share classes generally having different cash flow and control rights.

Determining cash flow rights in downside scenarios is critical to much of corporate finance, and the different classes of shares issued by VC-backed companies generally have dramatically different payoffs in downside scenarios.

The way the VCs mislead the press and the general public is how that they assign a valuation after each round of fund-raising assuming all classes of equity have the same value. As the authors elaborate, using Square’s October 2014 financiang as an example:

Square was assigned a so-called post-money valuation, the main valuation metric used in the VC industry….

Many finance professionals, both inside and outside of the VC industry, think of the post-money valuation as a fair valuation of the company. Both mutual funds and VC funds typically mark up the value of their investments to the price of the most recent funding round. Square’s $6 billion figure was dutifully reported as its fair valuation by the financial media, from The Wall Street Journal to Fortune to Forbes to Bloomberg to the Economist.

The post-money valuation formula in Equation (1) works well for public companies with one class of share, as it yields the market capitalization of the company’s equity. The mistake made by even very sophisticated observers is to assume that this same formula works for VC-backed companies and that a post-money valuation equals the company’s equity value. It does not….

And here is the kicker: had this valuation (the last before Square’s IPO…) taken into account the claims all the other classes of equity had on cash flows, the authors calculate that the value of the common shares would have been a mere $2.2 billion, meaning the value was inflated by a whopping 171%.

And the paper confirms that just as in private equity, where everyone knows valuations are often sus but no one challenges them because the path of better bonuses and PR lies with playing along, so to VC investors who presumably do know better report these bogus figures to their limited partners.

Back to the current post. Even though the analysis above shows the picture for venture capital is considerably worse than the not-very-pretty picture painted by Morgan Stanley, the Financial Times comments section is full of readers rubbishing the article and singing the praises of venture capitalists. It’s amazing how people convince themselves of their superior acumen despite being presented evidence that they are playing a mug’s game.