By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

“War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it.” —Letter of William T. Sherman to James M. Calhoun, E.E. Rawson, and S.C. Wells, September 12, 1864

On Veterans Day, I usually run an etching from Goya’s Disasters of War (gallery), because militarism and imperial triumphalism, of which we have a surfeit in this country, make my back teeth itch. This Veteran’s Day, what with our genocide in Gaza, our Ukrainian meatgrinder by proxy, our quest for escalatory dominance over Iran, and our pervasive “Real men go to Beijing” zeitgeist, I thought I would give Goya’s war art a little more attention; his subject, in essence, is the aspects of war the veterans you know may dream of, but very rarely talk about. First, I’ll take a brief, biographical look Goya’s art in the Peninsular War of 1807-1814 (Goya’s handwritten title on an album of Disasters proofs given to a friend reads: “Fatal Consequences of Spain’s Bloody War with Bonaparte, and Other Emphatic Caprices” (Fatales consequencias de la sangrienta guerra en España con Buonaparte, Y otros caprichos enfáticos). I’ll start with a short potted biography of Goya. Then I will look at one painting. Following a sidebar on Goya’s technique, I’ll look at three etchings from Disasters. The works speak for themselves and should be looked at slowly; to that end, I’ll try to be strong on technical detail and leave the interpretation up to you. I’ll conclude with some 30,000-foot musings.

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes

The great Australian critic Robert Hughes, whose biography Goya you might add to your tsundoku, wrote:

What lay before Goya as the 18th century turned its corner into the 19th? Steady work, at rising prices, for the court and nobles; security, wealth and honour in an encroaching old age. The idea that Goya was, or ever had been, a social rebel is simply untrue. His art, even at its most radical – a phase still to come – was a horrified protest against disorder and superstition, not a call to irrationality. As first painter to the king he was doing really well and as long as the court held, he would continue to reap its fruits. (In 1812, when he was 66, his house, furni ture, possessions and cash in hand were worth, in aggregate, about 350,000 reales.) As a portraitist he had no rivals.

[But then] Spain was plunged into what were, in effect, two wars. The first was a formal affair of arching armies and proper battles – Wellington and his generals versus Napoleon, the Peninsular war. The second was an internal war of Spanish irregulars against, in part, other Spanish factions and, especially, the hated French. The “guerillas” (as they called themselves) were poorly armed. Napoleon was not the last general to make that mistake about guerillas.

After 1814 Goya had to show he had been loyal to Spain during the Napoleonic occupation – otherwise he would have lost his precious job as first court painter, after the restoration of Ferdinand. What he had really been doing, much of the time, was working on the series of 80 etchings known as the Disasters of War.

For reasons we don’t now know, these weren’t published during Goya’s lifetime. In fact they didn’t appear until 1863, 35 years after his death.

They are reflections on the evil, sadism and cruelty inherent in war itself. Goya doesn’t take sides, strange to say. French soldiers do dreadful things to Spanish peasants, partisans and women; but then, Spaniards do equally horrible things to the French, and to other Spaniards… The idea of the “noble proletariat” is very far from Goya’s thinking. He has seen too much. He knows too much. Now and again he permits himself a sort of hideously sardonic culture-joke, but generally he takes the war head-on, without irony, in a passion too deep even for tears. In these etchings Goya junks all the issues of “glory”, “patriotism” and the rest. It is a tremendous, mesmerising achievement and it spills over into his paintings as well.

The Third of May 1808

Of this painting, Hughes writes:

On May 2, 1808, in the heart of Madrid, a crowd of citizens attacked a detachment of Mameluke (Moorish) cavalry led by a French general. The next day, May 3, the French struck back. Six years later, in 1814, Goya did two monumental paintings, so that these events should never be forgotten. The rising of May 2 1808 ( The Second of May 1808 ) and the execution of the partisans on May 3, 1808.

The Third of May 1808 is the picture against which all future paintings of tragic violence would have to measure themselves. It is truly modern, never surpassed in its newness, so raw that although it was a state commission it remained in storage, unseen by the public for the first 40 years of its life.

The surface is ragged: no smooth finish. The blood on the ground is a dark alizarin crimson smeared on thick and then scraped back with a palette knife, so that it looks crusty and scratchy, just like real blood smeared by the twitches of a dying body. You can’t “read” the wounds that disfigure the face of the man on the ground, but as signs of trauma in paint they are inexpressibly shocking – their imprecision conveys the thought that you can’t look at them.

I will stop there, since I would prefer you to focus on the painting.

Sidebar on Etching

From the Park West Gallery:

Instead of using color, Goya sought out bleak shadows and shade to express his stark views in “Disasters of War.” He did so through a combination of etching, drypoint, and aquatint.

Goya began his process by coating a copper plate with wax and etched lines into it with a sharp, needle-like tool. He then submerged the plate into an acid bath, causing the acid to bite at the exposed metal. The plate was then washed and the wax melted away.

Goya next employed the drypoint technique. He scratched onto the plate directly to create more textured, uneven lines in his compositions. Lines created this way are softer when final impressions are made.

To create additional tonal effects, Goya used the aquatint technique. This involves dusting a plate with a powdered resin and heating it until the resin melts and hardens. Acid is applied to the plate and eats away at the metal around the resin. As a result, small channels are created that will hold ink depending on how long they were exposed to the acid—the longer the exposure, the darker the ink appears on the print.

The final step in the printmaking process was to ink a plate and wipe away the excess, resulting in ink remaining in the etched lines. The plate was placed on top of dampened paper and run through a printing press, transferring a mirror image of the plate onto the paper.

Through this tedious process, Goya exposed generations of art lovers to the sobering realities of war. Goya is often considered one of the first modern artists and, through his “Disasters of War,” we can understand why—his unflinching commentary on war and morality speaks to us through time, impacting us in the present in ways few artists can.

One curator comments, in “Goya: Drawings from the Prado Museum” on the uses of these techniques in Disasters of War:

If we look at these works as prints, they violate all of the conventions of the preceding tradition of European etching. Murky pools of aquatint appear like pools of blood, the focus is personalised, immediate and confronting. Not only the limbs, but compositional structures are truncated and violated. So many of the artistic strategies advanced by Goya are not only pictorially confronting, but also pre-empt the devices of Expressionism and Surrealism of a century later.

Aquatint as pools of blood. Good to know. To the etchings—

Plate 7: Que Valor!

(“What courage!”). From the National Galleries of Scotland:

This print is notable among Goya’s ‘Disasters of War’ etchings as being one of the few to depict a well known event. It shows the heroism of a woman named Augustina Zaragoza (also known as Agustina de Aragon) during the 1808 Napoleonic siege of Saragossa. She is shown standing on the bodies of fallen Spanish artillerymen as she fires a canon at the French army. Her white dress stands out in stark contrast to the darkness of the canon and bodies. Augustina is said to have leapt to the defence of the city when she realised that the Spanish militia had been killed or too badly injured to fight, and according to legend she took the match to light the canon from the hand of a dead soldier. Her courage was renowned throughout Spain, and she was credited with having repelled the French army, on that occasion at least.

This is the one plate where Goya shows a heroic action. The issue of whether Goya was reporting or imagining will come up later, but here he seems to be reporting, although not from primary sources. (The white dress and the cannon barrel, I assume, are part of the plate where the acid didn’t bite in, hence no ink. Not exactly like working in LightRoom!)

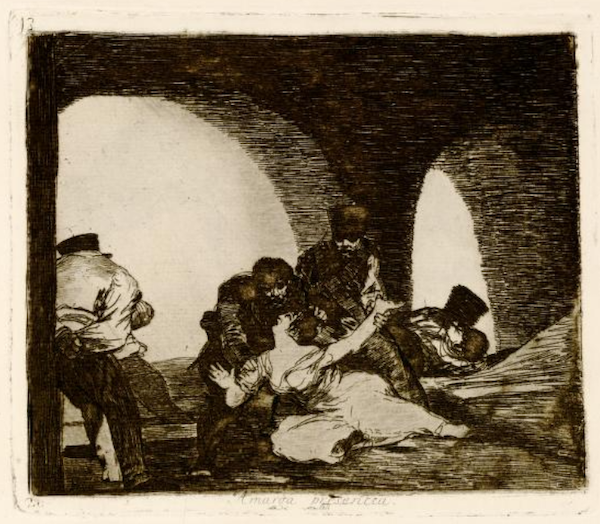

Plate 13: Amarga Presencia

(“Bitter Presence”). A post from “Every Painter Paints Himself” starts off with the brilliant observation that the painting resembles a skull, and the archways to the left are the holes for Goya’s eyes. It then devolves into an interpretation that is so like a combination of gender studies + “The Anxiety of Influence” that I refuse to quote it (it’s here). My own fanciful interpretation is that the soldiers are the “bitter presence” for the woman about to be raped, and the memory of the rape is a “bitter presence” for the artist, so bitter it persists into the grave after Goya’s death. We might also see the uninked parts of the plate (the world outside Goya’s skull; the woman) as the sweet light of reason, “present” but powerless.

Plate 39: Grande Hazaña con Muertos

(“A heroic feat! With dead men!”) Here is one amusing reaction from The Art Blog, “Goya’s emotionally charged art about war and human folly rings true today“:

I confess I was hard-pressed, while viewing works such as “A Heroic Feat! With Dead Men!” that depicts the naked and dismembered bodies of several men hanging on a tree, not to see them as mirror images of similar atrocities revealed in the press this past week regarding the rape, torture, and mutilation of Israeli women by Hamas soldiers on October 7 (not to confuse Hamas here with the majority of Palestinian citizens, also victims of the war).

But see AP, “How 2 debunked accounts of sexual violence on Oct. 7 fueled a global dispute over Israel-Hamas war.” From the National Galleries of Scotland:

In this sickening image, one of the most extreme in The Disasters of War series, the naked bodies of mutilated, tortured and castrated men are shown hung from a tree as a warning to others. Goya was one of the first artists to reveal the grim reality of warfare, stripped of all chivalry, romance and idealism. He captured something quintessential about modern war which has found resonance with succeeding generations of audiences. This print was controversially adapted in the 1990s by the artists Jake and Dinos Chapman. It formed the basis for one of their gory, three-dimensional tableaux, in which scenes from the series were recreated using dismembered mannequins covered in fake blood.

And what a trivial time the 90s were, to be sure.

Conclusion

The Library of Congress subject headings for Disasters of War are about as neutral is it is possible to be:

– Spain–Madrid, Comunidad de–Madrid

– Spain–Zaragoza

– 1810 to 1820

– Allegory

– Atrocities

– Death

– Famines

– Goya, Francisco, 1746-1828

– Peninsular War, 1807-1814

– Romanticism

– War casualties

I recently encountered this thread on wars between supercolonies of ants, also involving (no doubt) atrocities, death, famines, and war casualties, although (one assumes) not allegory or romanticism:

Many are aware that a world war between Argentine ant supercolonies is currently underway, across multiple continents, and against multiple ant ‘nations’. pic.twitter.com/EuJJ1PFq8D

— Stone Age Herbalist (@Paracelsus1092) November 8, 2024

If there are indeed aliens observing earth from far above the atmosphere, one might wonder whether they see war between ants and war between humans as all that different, considering what we humans make of ourselves.