Yves here. Wolf’s scenario on inflation is interesting, but given the welter of data revisions and forecast surprises, it seems fair to question whether what official reports depict now is any more accurate than what they seemed to say a month ago. Reader input on local and industry conditions very much appreciated.

However, even if inflation gets worse (which becomes likely regardless of the trajectory of the US economy if oil prices rise markedly and stay high as a result of the Middle East conflicts escalating), at some point it seems destined to tip into stagflation. Higher interest rates dampen borrowing and the valuation of companies with longer-term and/or speculative payoffs, which means tech above all. That means lower investment. A second channel by which inflation dampens investment is that over a certain level (which historically seemed to be 6% to 7%), the meaning of financial statements starts to become questionable because different line items inflate at different rates, and those differences matter. When I was a kid, choices like whether to use LIFO or FIFO accounting for inventories matter.

That produced uncertainty as to whether reported cash flows were accurately depicting the health of the company (for instance, use of historical asset values for depreciation would understate ongoing capital investment needs). That uncertainty had the effect of increasing investor required returns, pushing down stock valuations generally.

These considerations skip over how inflation, particularly in essentials like food and fuel, are politically destabilizing.

So that translates into an economy running too hot eventually becomes self-correcting. But the result, again, may be stagflation as opposed to recession.

By Wolf Richter, editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

When the Fed cut its policy rates on September 18, it looked at labor market data showing a sudden slowdown of job creation to weak levels, and it looked at decent consumer spending data, so-so income growth, and a very thin and plunging savings rate. And the trends looked lousy.

But starting 11 days after the Fed’s decision, the revisions and new data arrived. And the whole scenario changed.

So at a summary level, economic growth in three of the past four quarters, as revised, was substantially above the 10-year average of about 2.0% GDP growth adjusted for inflation:

- Q3 2023: +4.4%

- Q4 2023: +3.2%

- Q1 2024: +1.6%

- Q2 2024: +3.0%

The third quarter looks pretty good too: The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow estimate for Q3 real GDP growth is currently 3.2%, of which consumer spending contributes 2.2 percentage points, and nonresidential fixed investment contributes 0.9 percentage points.

In terms of the hurricanes and tornados that have caused a lot of destruction and horror: Because worksites were closed temporarily, and people had trouble getting to work, there will be a temporary spike in weekly unemployment claims and an uptick in unemployment in the affected regions. But the US has been through the horrors of hurricanes and tornadoes many times. What follows quickly thereafter is the spending and investment boom from clean-up, replacement, and rebuilding, which are all contributors to employment and economic activity.

A Bunch of Massive Up-Revisions After the Fed Meeting.

Consumer income, the savings rate, spending, GNI, and GDP were revised up on September 27, so 11 days after the Fed’s rate-cut meeting.

The annual revisions of consumer income and the savings rate were huge this time, going back through 2022, and consumer spending was also revised up, but not as much.

These massive up-revisions of income and the savings rate resolved a mystery: Why consumers have held up so well. And they brought growth of GDP and GNI (Gross National Income) back in line by revising GDP growth up some and GNI growth up a lot.

The magnitude of the revisions was astonishing, and we speculated here the large-scale influx of legal and illegal migrants – estimated by the Congressional Budget Office at around 6 million total in 2022 and 2023, plus more in 2024 – was finally getting picked up in some of the data. A big part of them have joined the labor force, and many of them are working and making money, and spending money, thereby increasing the income and spending data.

Between July 2022 and July 2024, over these two years, personal income without transfer receipts (so without payments from the government to individuals, such as Social Security, VA benefits, unemployment insurance compensation, welfare, etc.) adjusted for inflation:

The revisions to the savings rate are important because they showed that consumers spent substantially less than they made going back through 2022, and saved the rest, which bodes well for future consumption.

Income was revised up massively, and spending was revised up but less, and so the savings rate – the percentage of the disposable income that consumers didn’t spend – was revised up in a stunning manner: The revised savings rate for July was 4.9%. The old version of the savings rate for July was just 2.9%.

We have seen in the ballooning cash accounts, such as CDs, money market funds, and T-bills, that households are not only flush with cash but kept adding to their cash holdings, and we used this continued ballooning of cash holdings as a better signal of the health of consumers than the anemic savings rate. Now the massive revisions of the savings rate going back two years confirmed this.

The nonfarm payroll data was revised up on October 4, so 16 days after the Fed meeting.

The primary reason cited by the Fed for the 50-basis-point cut was the sudden deterioration of the nonfarm payroll data: The three-month average of payroll jobs created had slowed dramatically in July and August in part due to downward revisions of prior data, and we pointed that out at the time, it was a disconcerting sight.

But with the strong September jobs report came the up-revisions of prior data that prompted this headline here: OK, Forget it, False Alarm, Labor Market Is Fine, Bad Stuff Last Month Was Revised Away, Wages Jumped. No More Rate Cuts Needed?

“Pandemic distortions and millions of migrants suddenly entering the labor market, who are hard to track, have wreaked havoc on data accuracy,” we said in the subtitle. There is nothing like data whiplash.

It also solved another mystery: The weak payrolls data for July and August didn’t match other employment data, which had been fairly good.

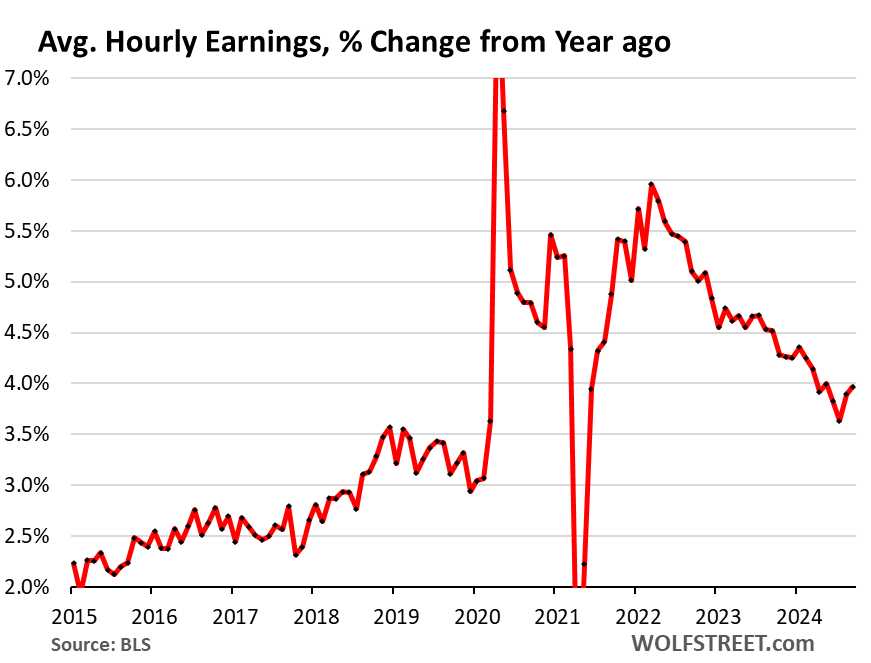

The increases in hourly earnings were also revised higher, with the revised three-month average income growth rising to 4.3% annualized.

The year-over-year increase rose to 4.0% for September, the second month in a row of year-over-year increases. Those two months combined increased the most for any two-month period since March 2022, and are well above the peaks of the 2017-2019 period.

“So in terms of inflation – and what the Fed has been worrying about – this accelerating wage growth is not going in the right direction anymore,” we said at the time.

And so Inflation Is No Longer Going in the Right Direction

Energy prices have plunged, and that has papered over the problems beyond energy.

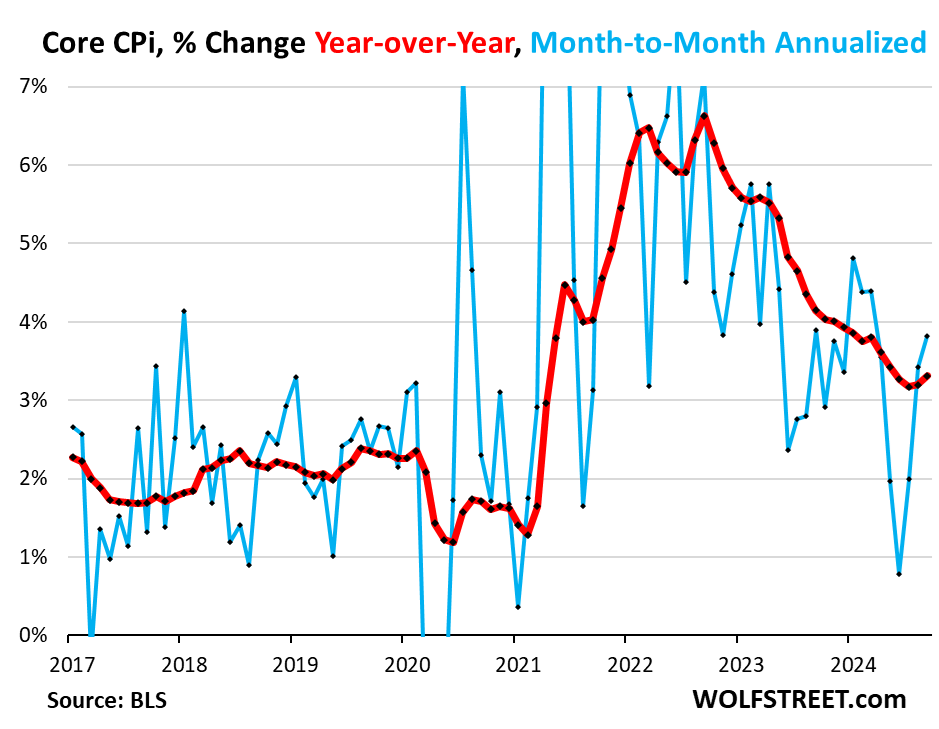

Core CPI, which excludes energy products and services and also food, accelerated for the third month in a row in September to +3.8% annualized (blue line), which caused the 12-month rate to accelerate to 3.3% (red line).

Inflation in services has turned out to be sticky. And then there are motor vehicles, where prices had been falling – plunging for used vehicles – which had been a big factor in pushing down core CPI since mid-2022. But they U-turned in September and headed higher (for details, see our “Beneath the Skin of CPI Inflation”).

This is not red-hot inflation like it was two years ago, it’s a lot lower than that, and the Fed has succeeded in bringing inflation down, but it’s re-accelerating inflation that’s still too high to begin with.

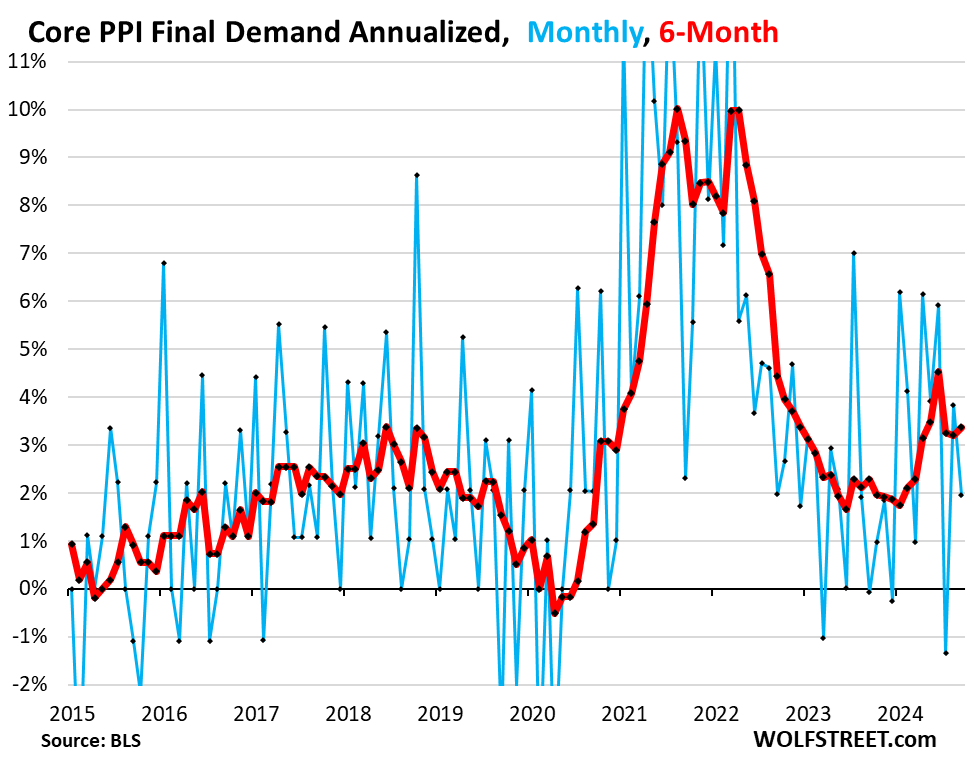

Inflation at the producer level – beyond the plunge in energy prices – has been going in the wrong direction all year, driven by accelerating inflation in services, after benign readings last year.

And on Friday, the core Producer Price Index was made a lot worse by big up-revisions of prior months, which caused the six-month average (red) to accelerate to +3.4% annualized for September. Last year, it had hovered nicely around the 2% line.

The Fed’s Policy Rates Are Still Well Above Inflation Rates

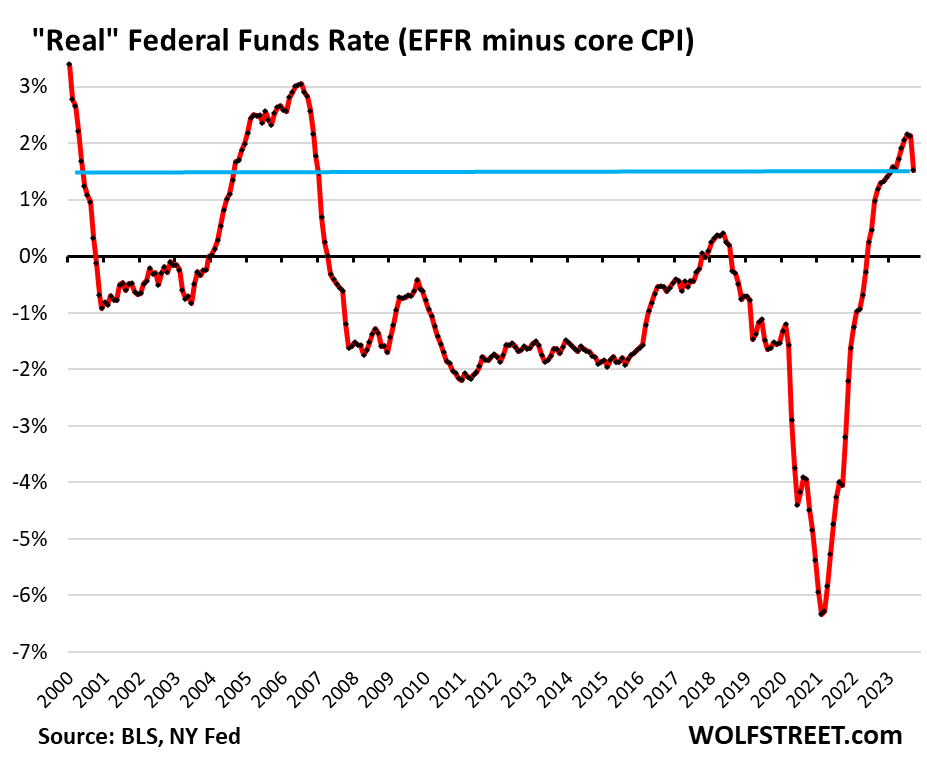

The Effective Federal Funds Rate (EFFR), which is targeted by the Fed’s policy rates, dropped to 4.83% after the rate cut, so that’s about 1.5 percentage points above the 12-month core CPI inflation rate. EFFR minus core CPI represents the “real” EFFR, adjusted to core CPI inflation.

The zero-line marks the point where the EFFR would equal core CPI. During the ZIRP era following the Financial Crisis, the real EFFR spent most of the time in negative territory. In 2021, as inflation exploded and the Fed was still at near 0% with its rates and doing $120 billion a month in QE, the real EFFR plunged historically deep into the negative. The Fed called this phenomenon “transitory,” and we called the Fed “the most reckless Fed ever” (google it, just for fun):

The assumption by the Fed is that policy rates that are substantially above inflation rates are above some theoretical “neutral” rate, and therefore are “restrictive.”

Fed governors have diverging opinions of where the neutral rate might be, since no one knows since it’s just a conceptual rate, and therefore diverging opinions on just how restrictive the current policy rates are – but they agree that they are restrictive, at least to some extent.

But what we’re seeing in the economic data is that policy rates may not be restrictive after all, that the “neutral” rate may be higher.

Yet the Signals Diverge

Some sectors have gotten hit really hard by those higher rates, especially commercial real estate, which has been in a depression for two years. For CRE, which had entered into a frenzy during ZIRP, financial conditions are strangulation-restrictive now. But that may be helpful in wringing out some of the excesses and in repricing properties to where they make economic sense.

Manufacturing, after the boom in manufactured goods during the pandemic, has been about flatlining at a high level.

But other sectors are flying high and are ascending further, including consumers.

At the extreme end of the highflyers, the spectacular bubble in AI triggered a vast investment boom – from construction of powerplants and data-centers – fueled apparently insatiable demand for specialized semiconductors, stimulated hiring and even office leasing, stimulated waves of corporate spending and investment, and waves of investments by venture capital in startups with AI in their descriptions. For anything related to the AI bubble, interest rates appear to be hugely stimulative.

Given where inflation is currently – 12-month core CPI at 3.3% – and where the Fed’s policy rates were before the rate cut – at 5.25% to 5.5% – it made sense to cut rates to bring them closer to the inflation rates, but keeping them well above the inflation rates.

The media has declared victory over inflation, not the Fed

The problem arises if inflation gets on a consistent path of acceleration. Powell and Fed governors have pointed at this risk many times. They’re fully aware of this risk. They’re leery of inflation going the wrong way again in a sustained manner. Inflation has been going the wrong way in recent months, but for a sustained acceleration, we’d need to see a lot more bad data, given how volatile the data is, to establish a solid trend. And they’re leery of that. They have not declared victory and have said so. But the media has declared victory over inflation, no matter what the Fed or the data say.

If there is an acceleration of inflation, the Fed can pause rate cuts for more wait-and-see. And if incoming data before the November meeting go in that direction, wait-and-see would be a prudent thing to do.

And if wait-and-see doesn’t work in halting the acceleration of inflation, if rates are not restrictive enough to hold inflation down – this likelihood rises with each rate cut – the Fed can hike again. Rate cuts are not permanent. Those scenarios are starting to show up on the horizon again.

The current situation also suggests that higher rates may actually be good for the overall economy, especially over the longer term, including for the reason that a considerable cost of capital fosters better and more disciplined and more productive decision making.