Yves here. We’re doubling up on environment-related posts today to make up for having neglected this area a bit of late. This offering crystalizes an issue I have not articulated myself, and I realize also contributes to my annoyance with electric cars as climate change hopium. We need far more radical reductions in energy and materials use to have any hope of escaping worst outcome that pretty much all Green New Deal schemes contemplate. The Green New Deal is at its core, “Let’s use techno-fixes, better shopping, and some mild activity dis-incentives to allow us to preserve the way we do business now.”

Aside from the near-necessity of cars for dispersed single family homes, another climate-costly addiction, the auto industry is a massive source of economic activity, both directly and through procurement and sales networks (and in the US, financing!). As proof, look at how the US is fighting tooth and nail to prevent the entry of cheap Chinese EVs, which would eat considerably into the sale of US EVs and conventional cars. It’s too late now, but if we had more lead time, imagine the economic displacement caused by a serious and well funded effort to improve public transportation (even with that more forceful measure not being adequate either). Horrors!

Opening comment by Bill Haskell at Angry Bear. Original text by Emily Atkin and published at Heated

Contrasting EVs to gas powered vehicles. And will EVs be as bad or worst that gasoline powered vehicles. And some promoters of EVs go in the opposite direction over promoting EVs or what the article calls green washing EVS.

~~~~~~~~

Financially motivated EV misinformation comes from both sides of the aisle (the lane?). Industries that see EVs as a threat exaggerate their harms in a bid to get you to hate EVs. And industries profiting from EVs greenwash their benefits in a bid to get you to love EVs.

Most often, you can recognize EV misinformation by its attempts to promote black and white thinking. It’ll either be “Electric cars are bad and gas cars are good” or “Electric cars are good and gas cars are bad.”

But the truth is, when it comes to the environment, there really is no such thing as a “good” car. The real question is: how bad are these cars in relation to one another? This is where most EV misinformation lies.

Misleading: It’s more environmentally harmful to make an EV than a gas car.

This statement, by itself, is technically true. ”To run, EVs require six times the mineral input, by weight, of conventional vehicles, excluding steel and aluminum,” the Washington Post reported in 2023.

That’s because each EV has a 900-pound battery block containing roughly 353 pounds of crucial materials or metals including cobalt, nickel, lithium, manganese, aluminum and copper. Gas cars don’t have that, so it’s less emissions-intensive to create a gas car than an electric car.

What’s misleading about the statement is not the statement itself, but the context in which gas car proponents say it. Usually, they’re saying it to convince you that electric cars are way worse than gas cars for the environment. And that’s just frankly illogical, because the vast majority of pollution that comes from cars does not come from making the car. It comes from driving the car.

If you’re only buying a car to simply look at it and never drive it, then absolutely, it would be way more environmentally-friendly to buy a gas-powered car.

But if you do, in fact, intend to actually drive the car you buy, then an EV is going to be the less environmentally harmful choice—even if coal is part of your local electricity mix.

That’s not according to me, either. That’s according to a peer-reviewed study funded by the Ford Motor Company, a company that makes most of its profits from gas-powered vehicles.

That study, conducted by the University of Michigan, found that EVs become less emissions-intensive than gas cars after “1.4 to 1.5 years for sedans, 1.6 to 1.9 years for S.U.V.s and about 1.6 years for pickup trucks, based on the average number of vehicle miles traveled in the United States.”

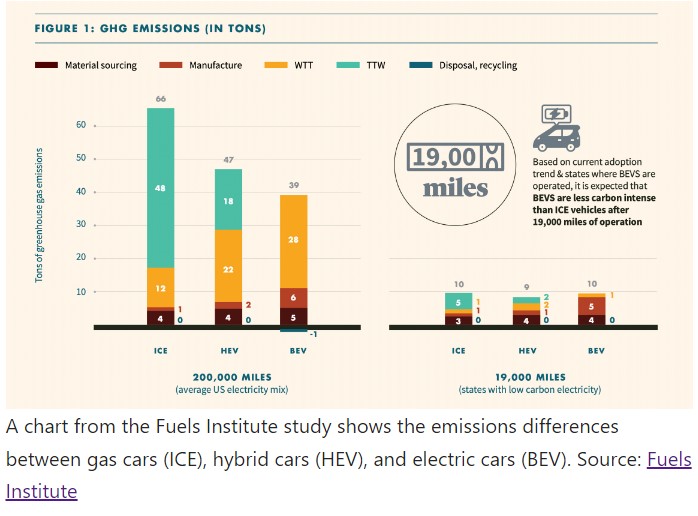

Another study, conducted by Ricardo PLC for the nonprofit Fuels Institute, similarly found that driving a gas car is far worse for the planet than EVs, even when coal is part of the electricity mix.

Over 200,000 miles of driving, it found, a gas car emits 66 tons of greenhouse gas emissions, while an EV using the current average U.S. electricity mix emits 39 tons. In states that already have low-carbon electricity, an EV becomes less emissions-intensive than a gas car within 19,000 miles.

As time goes on, experts expect that it will take less and less driving time for EVs to become cleaner than gas cars. That’s not only because the electricity mix is expected to become cleaner; but also because the majority of battery materials used to make the cars are likely to be recycled.

Recycling and reusing the minerals used to make EV batteries “will drastically cut down the amount of wasted material compared with fossil fuels which disappear invisibly but harmfully to heat the planet,” the Guardian noted in December. The story cited data that suggests that “after recycling, battery material waste over an electric car’s life will be about the size of a football, or 30kg, by 2030.”

Of course, we all know how trustworthy corporations have been about recycling. But the point stands: anyone who says the creation of EVs makes them environmentally worse than gas-powered vehicles is either misinformed or trying to mislead you.

Myth: Because gas-powered cars are worse for the environment, we don’t need to worry about the harms of EVs.

Gas-powered cars are worse for the environment than EVs. But this does not mean EVs are good for the environment. Anyone telling you that is either misinformed or trying to mislead you.

In a recent investigation of this same debate, the Guardian found that gas vehicles were worse for the planet than electric vehicles. But it also ended on this important note: “the green credentials of electric cars [do not] absolve the buyers of battery minerals of responsibility for abuses in the supply chain.”

As Washington Post climate advice columnist Michael J. Coren wrote last year:

Mining minerals is never a clean affair. Cobalt from Congo, lithium and graphite from China, nickel from Indonesia and Russia, and battery supply chains that run through Xinjiang, in the Uyghur region where forced labor has been rampant: All of these have immediate problems, which The Washington Post explored in our “Clean Cars, Hidden Toll” series. Guinea, home to the world’s largest bauxite reserves for aluminum, yields misery for local communities. Nickel refiners in Indonesia are adopting a risky technology. Mineworkers in South Africa, the world’s largest producer of manganese, face neurological ills.

“The transition to low-carbon fuels is not a magic bullet with no negative outcome,” Sergey Paltsev, a senior research scientist at MIT, told Cohen. “There is no free lunch. But it’s much less harmful than if we stay with fossil fuels. That’s the conclusion.”

Misleading: The U.S. electric grid can’t handle widespread EV adoption.

HEATED reader Oscar asked us to research the widespread claim that a large increase in electric vehicle adoption would place massive stress on the U.S. electric grid.

Oscar also wanted to know how much current U.S. infrastructure would need to be updated to accommodate a massive increase in EV adoption.

For a really detailed answer to both questions, I recommend reading this 2022 article in Scientific American, “Why Electric Vehicles Won’t Break the Grid.” But if you don’t have time, here’s the gist in one quote:

“We can’t just sit back and say, ‘OK, the grid can handle it; it’ll take care of itself,’” Baldwin added. “It will take attention, and it will take some adjustments to how things have been done in the past, but all in all, I’m optimistic that this is something that we can do.”

A big conclusion I took from the article is how much gas car proponents are exaggerating the strain on the grid from EVs:

In California—the national leader in electric cars with more than 1 million plug-in vehicles—EV charging currently accounts for less than 1 percent of the grid’s total load during peak hours. In 2030, when the number of EVs in California is expected to surpass 5 million, charging is projected to account for less than 5 percent of that load, said Buckley, who described it as a “small amount” of added demand.

But as people continue to buy EVs—and they are, across the world—it’s true that utilities will need to make adjustments to accommodate increases in demand. But experts say it’s not the huge deal gas car proponents are making it out to be.

“We’re talking about a pretty gradual transition over the course of the next few decades,” said Ryan Gallentine, transportation policy director at Advanced Energy Economy. “It’s well within the utilities’ ability to add that kind of capacity.” …

That success will hinge on utilities being proactive in planning for millions of additional EVs on the roads in the coming decades. It will also take some adjustments, experts said. EV owners and utilities must take advantage of up-and-coming charging technologies that will save the grid from unnecessary stress.

More EV Claims, Untangled

The Guardian’s “EV mythbusters” series, written by financial journalist Jasper Jolly, has been incredibly helpful in furthering my own understanding of EV misinformation.

Here are some of the questions Jolly tackles, and key quotes from his findings if you don’t feel like reading the whole thing:

- Do electric cars pose a greater fire risk than petrol or diesel vehicles?

Key quote: “‘All the data shows that EVs are just much, much less likely to set on fire than their petrol equivalent,’ said Colin Walker, the head of transport at the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit thinktank.” However: “There is a definite puzzle for firefighters, as battery fires require more water to put out, can burn almost three times hotter, and are more likely to reignite, according to EV FireSafe.” - Is it right to be worried about getting stranded in an electric car? Key quote: “Banishing range anxiety is tricky because it relies on electric vehicles’ use patterns as well as the charging network. It is not yet possible to say that every journey is well served … Most authorities are clear, however, that range anxiety should not be a problem for most people.”

- Are electric cars too heavy for roads, bridges and car parks?

Key quote: “Some car park owners may be affected, and if electric trucks are heavier when they become widespread that could add to road maintenance costs.But almost all of the direct costs will be borne by infrastructure maintenance budgets. The ECIU’s Walker said concerns about extra weight for EVs were simply “massively overstated”. However, he added that carmakers do have a responsibility to produce smaller electric cars, after years of focusing on the most profitable SUVs.” - Do electric cars have an air pollution problem?

Key quote: “It is certainly the case that ever heavier cars almost certainly produce more [tire] particulates. Electric cars are – for now – heavier still than equivalents. But even so, [tire] pollution appears roughly comparable between petrol, diesel and electric cars.” - Are electric cars too expensive to tempt motorists away from petrol and diesel vehicles?

Key quote: “For mostly urban drivers in cities such as Los Angeles, it “makes a lot of sense” financially but it is another calculation for Texas highway drivers, Shivers said. “It’s going to be very person-specific because everybody’s case is different,” he added. - Will hydrogen overtake batteries in the race for zero-emission cars? Key quote: “The answer is no,” said Liebreich, without a moment’s hesitation. Carmakers betting on a large share for hydrogen are “just wrong”, and heading for an expensive disappointment, he added.

EV mythbusters, The Guardian, Jasper Jolly