Yves here. This post by John Helmer underscores the degree to which Russia approaches war differently than the West. Despite the micro focus and emotion-button-pushing of some Russian commentators, a, arguably the, guiding principle for Russia’s conduct of war is economy of force. From that follows the preference for attritional warfare, the willingness to cede territory to save resources, and a studied indifference to how long things take. Needless to say, this disparity from the US approach leads to regular misinterpretations of the Ukraine campaign.

Helmer translates and reposts an analysis by Yevgeny Krutikov, formerly a military intelligence officer of the GRU, of why the fight for Pavlovka, in southern Donetsk, which has become controversial due to claims of high losses for the Russian side (which are actually small compared to typical Ukraine deaths and casualties) is important as a check on possible Ukraine offensive strategies.

By Yevgeny Krutikov, introduced and translated by John Helmer who has been the longest continuously serving foreign correspondent in Russia. Published at Dances with Bears

The problem of interpreting the war from the Russian point of view is that the Russian military does not signal its punches, make idle threats, believe its own propaganda, or make money on click bait. The Stavka never leaks.

By contrast, Russian open-source commentators are driven, as is normal in a functioning democracy, by domestic politics. This requires them to disguise or camouflage their support for or opposition to the political and oligarch factions in Moscow with a variety of ploys — attacks on named generals; analyses of the Army’s mistakes; speculation about the negotiations initiated by US officials with their Russian counterparts; warnings of Fifth Columns, stabs in the back, and a shameful peace.

The outcome in Moscow doesn’t exist in any European or North American capital — noisy debate with sharp dividing lines drawn between the factions of patriots (Tsargrad, Vladimir Soloviev); the left (Sergei Glazyev, Mikhail Khazin); the fakes (Yevgeny Prigozhin); the right (Elvira Nabiullina, Alexei Khudrin); the oligarchs (Oleg Deripaska); the puppets (Margarita Simonyan); and so on, not counting the oppositionists in hiding, exile or jail.

Easy to misread Russian military analysis then, because there is so much of it; because the Stavka doesn’t talk to any of them; and because for Russian commentators this is an opportunity for waging their contests for the usual things — power, money, celebrity. You will see criticism of President Vladimir Putin (lead image, 2nd left, rear), therefore, but always under cover of something or somebody else.

This is understandable because he and the war aims are so popular. Public support for Putin is currently ten points higher than it was in January of this year; three points lower than in April; two points higher than in September. There is nothing and no one comparable on the US or NATO side. Since the start of the special military operation on February 24, the Russian president’s approval rating has remained stable within a 4-point variance; that is roughly equal to the pollster’s margin for statistical error. This means that, strategically speaking, most Russians are almost as patient as the Stavka.

By contrast, the politics of the US and NATO side is an impatient, short-term business. A week is a long time in politics, the former British prime minister Harold Wilson once said, correcting Joseph Chamberlain, a nineteenth century predecessor who didn’t quite make it to the prime ministry; Chamberlain said it was two weeks.

Warfare is a longer term business. This war is going to be longer still.

To follow, understand, and anticipate as Russians do requires a form of thinking that can be called byzantine. Not the western meaning of deviousness, but the eastern meaning of the way the thousand-year Byzantine empire was ruled from Constantinople. In our time this starts with the doctrine of economy of force. Cost-effective calculations regulate the deployment of men and materiel, hence the changeable combination and schedule of fixed-wing air attack, helicopter air attack, missiles, drones, and artillery in Russian operations so far. The rules of war of attrition also apply, as do the tactical variables of positional and mobile warfare. By the time these variables are counted up, and multiplied by firepower and deception, this is thinking which goes far beyond games of chess or Go. Situation report maps in publication don’t help much; they are already days old and obsolete.

Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov’s (lead image, left front) strategy of the Golden Bridge, applied successfully against Napoleon, requires allowing the enemy the time and space to retreat and withdraw to his own territory because the cost of annihilating him on Russian territory is much greater and unnecessary. General Winter (centre front) also requires operational patience because the freeze doesn’t always deploy itself when the Russian army wants it. This year, however, it has begun already. Snow has started falling in Kiev; in a week’s time it will be minus 8 degrees Celsius. It remains warmer along the eastern front, and in Kherson.

Russian or byzantine thinking is the antithesis of the shock and awe doctrines of the US and NATO. Their journalists and staff colleges have invented terms to conceal their incomprehension of Generals Sergei Surovikin (front right) and Valery Gerasimov (rear right), and Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu (rear left). But they remain in the dark – as US Army Colonel (retired) Douglas Macgregor keeps trying to point out.

Byzantine thinking can’t be memorised, photocopied, or cribbed. To learn, start with this paradox of imperial impatience first published by C.P. Cavafy in 1904; he called it “Waiting for the barbarians”.

There is also what Russians say they are thinking will come next. Take it as carefully as you read Cavafy. What’s the hurry?

Yevgeny Krutikov was a military intelligence officer of the GRU before he became a journalist for the Moscow internet publication Vzglyad. Last Friday evening he published the following analysis which has been translated without editing. Maps have been added.

Source: https://vz.ru/

HOW ARE UGLEDAR AND THE PLANS OF THE UKRAINIAN OFFENSIVE AGAINST MARIUPOL CONNECTED

HOW ARE UGLEDAR AND THE PLANS OF THE UKRAINIAN OFFENSIVE AGAINST MARIUPOL CONNECTED

The winter campaign will have its own peculiarities

November 11, 2022

Text: Evgeny Krutikov

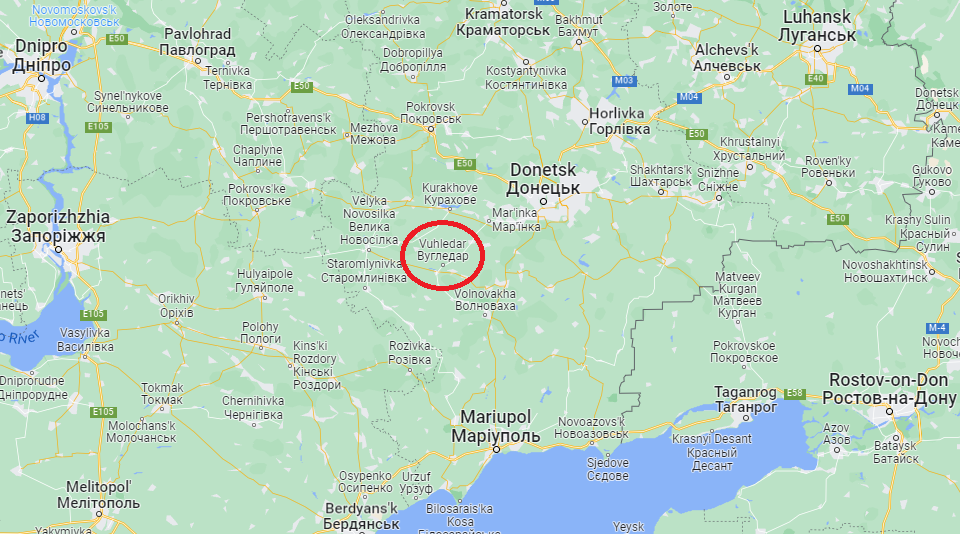

The town of Pavlovka, located in the Donbass, has been liberated by Russian troops. At first glance this looks like an insignificant event, especially compared to what is happening in the Kherson region. In fact, these two sections of the front have a direct connection, especially in relation to the upcoming winter campaign.

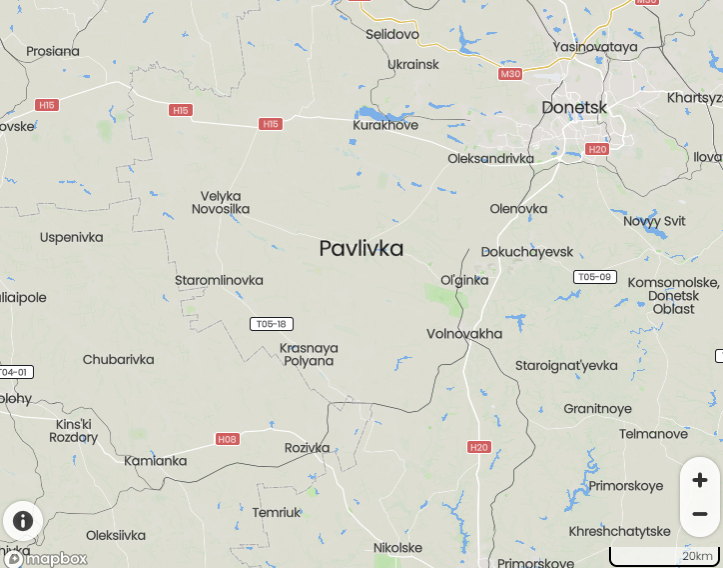

Source of map: https://mapcarta.com/

For video of Russian capture of Pavlovka, see this.

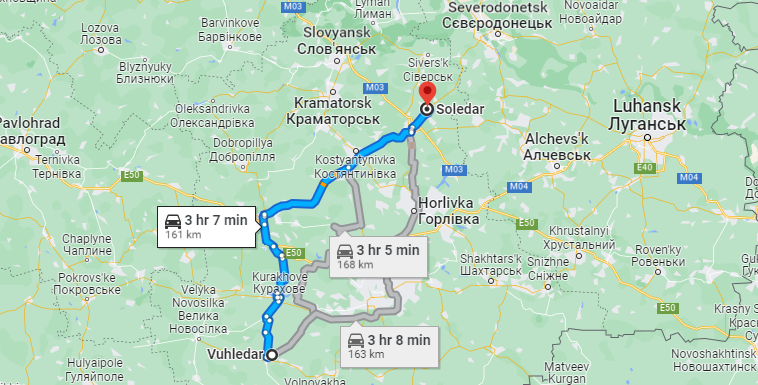

By Friday, November 11, Russian troops finally occupied Pavlovka and began to clean up, including the territory in the direction of Ugledar. Still, a full-fledged attack on Ugledar has not yet been observed.

Near Artemovsk, fighting continues for the suburban settlements, especially Opytnoye, without taking which it is impossible to talk about a further offensive on Artemovsk. About the same story with the battles for Soledar. There are already fighting units in the city, but without control over the suburban villages of Belogorovka (to the north) and Bakhmutsky (to the south), the situation in Soledar will be unclear.

There have been no significant changes in the Avdeyevka direction — there are battles for Opytnoye (not to be confused with the same-named Opytnoye near Artemovsk) and Vodyanoye; Pervomaiskoye is being cleaned out. A slight advance was also noted in Maryinka.

What is happening in this sector of the front may seem small-scale compared to the regrouping of forces on the left bank of the Dnieper. The enumeration of the names of little-known Donbass villages didn’t say much to the average Russian even before this. Nevertheless, right now – after the relocation to the left bank of the Dnieper – it becomes more important than ever before to understand what will happen next. At least in the time perspective of the winter and spring.

Taking into account the balance of forces as a whole along the entire line of contact, we can say with a high degree of confidence that there will be no more serious positional movements until the end of November. The stabilisation of the front along the Dnieper River and along the established line in the north from Kremennaya to Kupyansk is a stabilizing event by itself. Russian troops are thereby given the opportunity to release those units which have been under shelling, and transfer them to other sectors of the front which the command deems important.

Another thing is that the VSU [Armed Forces of Ukraine] has also been redeploying 4 to 5 brigades. There is no big doubt where they will transfer them. The enemy has been pushing all the reserves at its disposal for several months, including newly formed and numbered brigades, to the arc from Ugledar to Soledar. That is, exactly where the Russian army is leading the offensive and where Pavlovka is located.

Some small settlements in that area have already been turned into a kind of medieval encampment; there are ten times fewer civilians in them than reservists. In this sector of the front (in a broad sense, throughout the Donetsk arc), the enemy has been building a line of defence for years which resembles in its configuration not even the Second World War, but in some places the First World War.

The defence line of the VSU north of Donetsk airport and the famous village of Peski has even officially been called the Big and Small Anthills – that’s because of the abundance of trenches and other fortifications. It was possible to clean up this ‘Ukrainian Verdun’ only last week, but right now the fighting is going on at the outskirts of these ‘anthills’ – in the villages of Vodyanoye, Opytnoye, and Pervomaiskoye.

There’s an idea circulating that the current battles on the Avdeyevka arc [дуга] are something unimportant and meaningless. In reality, this is not the case, and the enemy is clinging to these positions to the last for good reason. There, as well as on the Seversk– Soledar–Artemovsk line and further to Chasov Yar and the Slavyansk-Kramatorsk agglomeration, almost a quarter of the entire Ukrainian army has been pumped at the moment. And reserves are constantly arriving. So no one has terminated the spring task of destroying the VSU grouping around Donetsk and Avdeyevka. Not to mention the fact that this is the territory of Russia all the way to Slavyansk.

Another thing is that now there are no prerequisites for the encirclement of this grouping, and there is a classic passage through the enemy’s fortifications. And this is not only a purely military issue, but also a political one. There is no alternative to fighting for positions around Avdeyevka and for the Slavyansk-Kramatorsk agglomeration in the broad sense of the word. Not under any command nor under any strategic plan, whatever it may be.

Weather conditions will change the nature of tactics somewhat, but in general the situation will not change. Fighting in the DPR [Donetsk People’s Republic] is basic, fundamental, for which everything will be sacrificed. If you want, this is the quintessence of the special military operation. Such is the geography, with which you cannot argue. Be you even Suvorov [Marshal Alexander Suvorov 1730-1800], even Zhukov [Marshal Georgy Zhukov 1896-1974], but you will not be able to avoid the continuation of trench fighting in the arc from Maryinka to Seversk.

The enemy also needs a respite, especially since the five brigades of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, which have been pressing on Kherson, are now severely battered. In their condition, it’s quite impossible to take them and throw them somewhere else to organize some new offensive. They require additional equipment, rest and rearmament. So it’s simple — the VSU will be forced to take a break, despite the fact that there are rumours about an upcoming offensive in the southern sector.

There is euphoria in Kiev, and even the foreign advisers who manually manage the Ukrainian general staff cannot dissuade these people from further movements. At the same time, the need to constantly bring reserves to Chasov Yar reduces Kiev’s chances of forming a new offensive grouping.

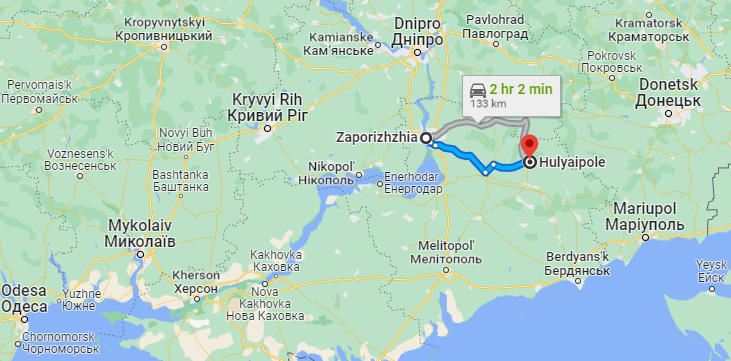

Nevertheless, it is the southern direction which should be recognized as the most important. In Kiev they look at the map and see that the distance to the coast of the Sea of Azov (Berdyansk, Melitopol, and Mariupol) from the front line is about two hundred kilometres. That’s not far.

But in order to advance in this direction, the VSU must hang on to Ugledar. Ugledar is of critical importance for the VSU in order to try to develop an offensive against Mariupol from the north. Without controlling the Ugledar area, the VSU units advancing to the sea risk getting a stab in the back. That is why it is extremely important for the Russian troops, in turn, to clean up the approaches to Ugledar – the very settlements of Pavlovka and Novomikhailovka, even Maryinka. The occupation of Ugledar by Russian forces, or at least fire control over this zone, by itself prevents the possibility of a Ukrainian offensive to the coast of the Sea of Azov.

Although, given the euphoria in the minds of Kiev, they may well try to attack even with their flanks exposed.

Another option for the development of the winter campaign may be the organisation of a Russian offensive on a less than obvious sector of the front. Previously, a compensating counterattack in the Kharkov region was considered as such after the stabilisation of the front there. But on reflection, it is clear that this is too costly and risky. The enemy is exhausted in this area, but it is still unclear what its possible reserves are.

Another option can be considered on the southernmost flank, most likely in the direction of Zaporozhye. But not the area which the enemy considers as its possible springboard, but the territory from the Dnieper to Gulyai-Pole, where troops will be withdrawn from the other side of the river. This is possible, however, only after the end of the regrouping and the formation of new units from among the mobilised.

To be sure, all these scenarios can be implemented on condition that there are no unexpected changes in the terms of Russia’s strategic approach to the military action. So far, such changes are not visible. But in any case, the winter campaign will bear little to no resemblance to the summer-autumn one.