Yves here. Richard Murphy presents a provocative analysis on the role of interest rates in inflation. I’m not convinced, since I assume most businesses try to have a fair bit of longer-maturity debt, and would thus only be partly exposed to central bank interest rate increases. Where those will bite first is for funding new projects, since most investors like to use at least some borrowed money.

Perhaps the better question is in what sectors is Murphy’s analysis most likely to apply, as in which companies (ex financial services companies) borrow mainly short term or at floating rates?

By Richard Murphy, a chartered accountant and a political economist. He has been described by the Guardian newspaper as an “anti-poverty campaigner and tax expert”. He is Professor of Practice in International Political Economy at City University, London and Director of Tax Research UK. He is a non-executive director of Cambridge Econometrics. He is a member of the Progressive Economy Forum. Originally published at Tax Research UK

I have been suggesting that interest rate rises are fueling inflation.

That idea might, it seems, shock the Bank of England. They seem to think that inflation is down to excessive pay increases. However, I have some news for them, which is that employees do not set price increases. It is companies that do that. In that case, let me put forward a model of a company that is largely service-based to explore my suggestion.

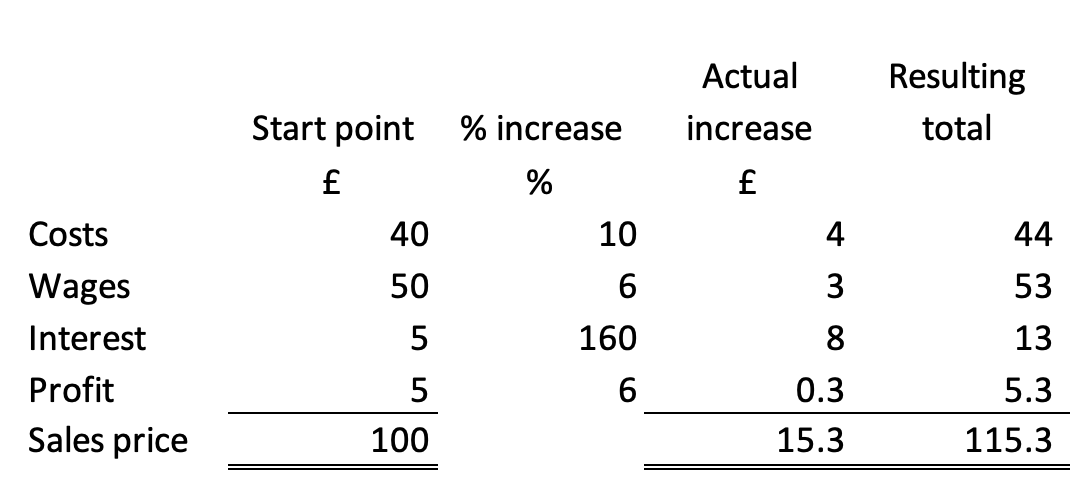

This is the starting point for this model:

The figures have been chosen for purely representational purposes: they are denominated in monetary units (thousands, tens of thousands, or millions: it makes no difference) but also, in effect, indicate the percentage split in the cost base of the company. The proportion of wages suggests it is service orientated, as most companies are.

Then I suggest that adjustments for inflation be taken into account, as follows:

Bought-in costs have increased by 10% – roughly the rate of inflation in the last year.

Wage increases have been kept to 6% – which will be tough on many staff.

The big increase is, however, in interest costs. The company pays interest at 3% over bank base rate. So, the rate has grown from near enough 3% to 8%, or a growth of about 160%.

In comparison, profits have only been targeted to increase at the same rate as wages.

The resulting overall cost increase is 15.3%, with more than half of that being due to interest, which imposes a bigger cost increase than external costs and the wage settlement combined.

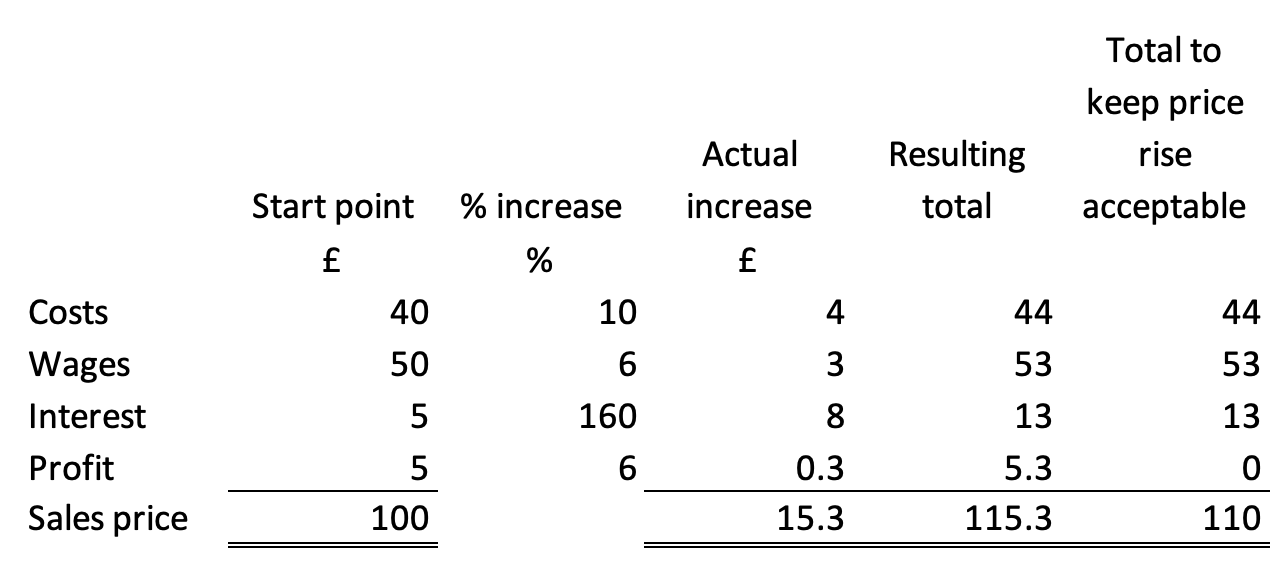

Let’s presume the company realises that the market will not accept a 15.3% price increase, and it keeps it to 10%. This is the result:

Profits have now been eliminated. The company’s future is, then, in doubt.

I stress that this is a model.

I would add that the assumptions seem fair, as does the cost structure, although these (of course) vary widely.

My points are threefold. First, it is not wages that are driving up inflation.

Second, it is interest rate rises that are driving up prices.

And third, interest rate rises are now so extreme that many businesses will face the threat of failure.

The Bank of England is welcome to use this model and think about the consequences which they have created. Unfortunately, I suspect that they will not. That’s because what this model makes clear is that we face a crisis created in Threadneedle Street, but they have no understanding of what they have done and are doing.

And that’s why we face desperate economic times.