By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street.

Financial conditions for junk-rated companies have tightened only a little since the Fed started tightening in early 2022, from the loosey-goosey levels in 2021, and they remain loose by historical standards, though the Fed has jacked up interest rates by five percentage points in order to tighten financial conditions, including for junk rated companies. These junk-rated companies generally don’t have enough cash flow left over, after paying their operating expenses, to cover all their interest payments; in other words, they have to borrow new money to pay interest on existing debts, which puts them into a precarious spot when financial conditions tighten.

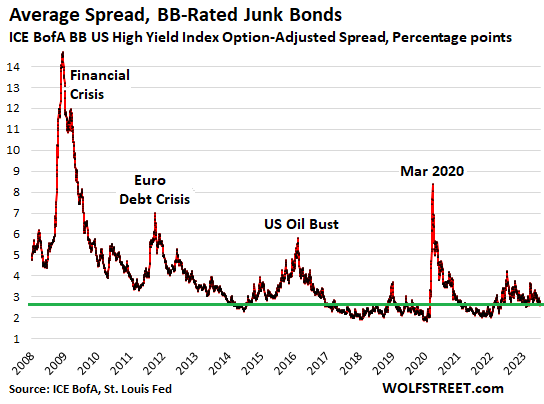

One measure of tightening financial conditions for junk-rated companies is the spread between junk-rated debt and debt that has no credit risk (Treasuries). For example, the average spread of BB-rated bonds, the upper end of junk (my cheat sheet for corporate credit rating scales by ratings agency) was just 2.66 percentage points as of Friday’s close (for an average yield of 7.13%).

That spread of 2.66 percentage points has narrowed from 3.6 percentage points in March during the bank panic, and from 4.1 percentage points in July 2022!

In March 2020, the BB-spread widened to over 8 percentage points. During the Financial Crisis, it widened to over 14 percentage points. So this spread of 2.66 percentage points is still narrow, still speaking of loose financial conditions, with investors still chasing yield and taking on risks with little extra compensation.

Here is the long-term view. This is one of the astounding signs of our times: still too much liquidity chasing yield, taking on big risks for little extra compensation, despite the Fed’s tightening:

Some Companies that Have Long Teetered Go Over the Cliff.

Lots of these overindebted junk-rated companies will have to restructure their debts in bankruptcy court at the expense of stockholders, unsecured bondholders, even secured bondholders, and holders of their leveraged loans. That’s part of the cycle, that’s how it’s supposed to work, that’s how the corporate-debt burden on the economy gets relieved.

Investors got paid to take those risks, and they took those risks to make money, and now those risks are coming home to roost.

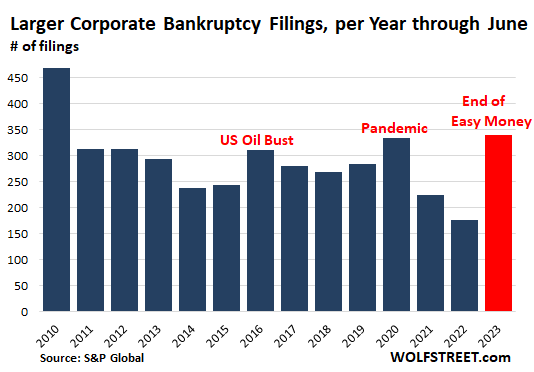

Bankruptcy filings by larger corporations in the first half of this year rose to the highest level since the same period in 2010, when they were coming down from the Financial Crisis.

Another 54 of these companies filed for bankruptcy in June, same as in May, bringing the first-half total to 340, according to S&P Global’s bankruptcy report for companies that are publicly traded whose bankruptcy filings list at least $2 million in assets or liabilities, and for private companies with publicly traded debt (such as bonds) whose bankruptcy filings list at least $10 million in assets or liabilities.

But they’re up by only 20% from the Good Times in 2019 and by only 9% from 2016, when the US Oil Bust sent a bunch of oil & gas companies scrambling for bankruptcy protection, though the Fed has now jacked up interest rates by 5 percentage points.

And in 2021 and 2022, bankruptcy filings had plunged to abnormal lows as the economy was awash in Easy Money trying to find a place to go.

During the pandemic, the Fed bent over backwards to bail out corporate America, including by buying corporate bonds and bond ETFs, including ETFs that focused on junk bonds. And it cut its policy rates to near 0%, and it bought trillions of dollars of Treasury securities and MBS over a few months, flooding the economy with what would ultimately be $4.6 trillion of insta-liquidity that went chasing after everything, and of course, now we have inflation.

So the Fed is now doing the opposite: interest rates are over 5% and QT marches on. And you’d think this rapid tightening – the most rapid in 40 years – would have a more serious impact on financial conditions and on bankruptcy filings.

And it’s sort-of astounding — I mean, nothing astounds us anymore here, but still — that the financial conditions are still so loose, and that corporate bankruptcy filings haven’t shot higher.

Sure, some badly managed banks collapsed, and SVB Holdings is included in this list of bankruptcy filings. Other companies finally filed this year that should have filed long ago but because of easy money were able to drag out the moment.

This included several big retailers – most prominently Bed Bath & Beyond, David’s Bridal, Christmas Tree Shops, and Tuesday Morning – that in 2023 finally joined the slew of big retailers that have filed for bankruptcy since 2017, and most of them were liquidated.

Their enemy wasn’t high interest rates and tightening financial conditions, but a structural change in how Americans shop: ecommerce. This retailer-bankruptcy-and-liquidation dance has been going on for years, and we here have covered it since 2017 under the category of Brick-and-Mortar Meltdown. And it will keep melting down year after year until it’s done, and tightening might only speed up the process.

Bankruptcies occur for a variety of operational and financial reasons, such as years of mismanagement and bad decisions (including over-the-top risk taking and binging on debt); structural changes in the economy, such as the shift to ecommerce; competition; inadequate cost controls; fraud, etc. And tightening is just a wakeup call. It enforces a discipline that ultimately produces better economic outcomes in the future.