By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street.

Tsunami of issuance meets Fed QT, Skittish Foreign Buyers, and US buyers demanding to be compensated for the risks of out-of-control deficits in an inflationary environment.

Yields of longer-dated Treasury securities have surged by about 150 basis points since April this year, from about 3.5% to above 5% for 20-year and 30-year yields, and to just below 5% for the 10-year yield, which has caused a historic bloodbath for holders of these securities and bond funds, such as the TLT. There is now a lot of navel-gazing in some quarters as to why this jump in yields could possibly have happened. And here and there, some fancy theories are getting trotted out.

But it boils down to supply and demand. Supply is a tsunami of Treasury securities being issued as the government has to borrow unspeakable amounts to fund its scandalous deficits even in a strong economy.

And this tsunami of supply must find demand. Yields must rise until they meet demand. Yield solves all demand problems. There will always be demand if the yields are high enough, so it’s not a question of finding buyers, but at what yield those buyers can be found.

And that’s what we’re looking at: To what level will 10-year yields have to rise to entice even me to buy some of them? For me, 10-year yields are not there yet. And as each wave of issuance gets bought, new buyers need to be enticed with sufficient yields.

Obviously, something could change that would lower yield expectations by potential buyers, such as inflation miraculously vanishing or something scary happening that will make even an unappetizing 10-year yield look better than the alternatives. But we’re not there yet.

Here’s the tsunami of supply.

The total amount of Treasury securities outstanding has now reached $33.6 trillion. Of that amount, $7.1 trillion are securities held by government entities, such as government pension funds, the Social Security Trust Fund, etc. They’re not traded, and those entities buy the securities directly from the government, and so they don’t have a direct impact on supply and demand in the market.

The remainder, $26.5 trillion, are Treasury securities held by the “public.” The public includes foreign holders, the Fed, banks, bond funds, insurance companies, individuals, and me (only T-bills so far).

These securities held by the public spiked by nearly $1.8 trillion in the five months since the end of the debt-ceiling standoff, and by over $10 trillion, or by 65%, in five years, from $16 trillion in January 2019 to $26.5 trillion now!

This new issuance of $1.8 trillion in five months needed to find buyers. And yields must rise until every last one of these securities is purchased by the “public.”

And here is demand by the biggies: International holders and the Fed.

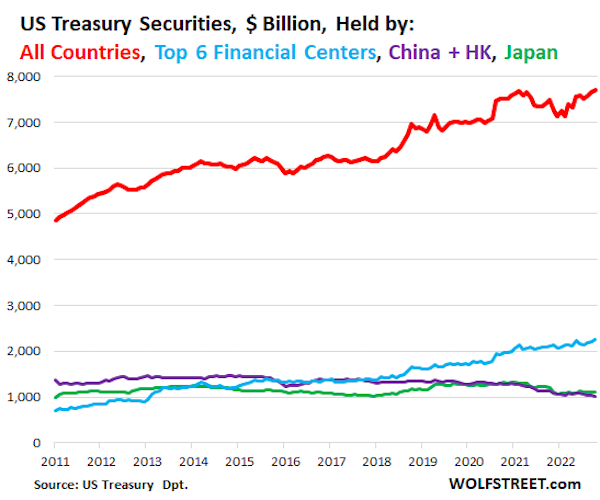

International holders are still buying but not keeping up. They increased their holdings of Treasury securities to a record $7.71 trillion in August, as of the latest TIC data by the Treasury Department (red line in the chart below):

- Japan, #1 US creditor, increased its holdings to $1.12 trillion (green).

- China and Hong Kong combined, #2 US creditor, further reduced their holdings to $1.01 trillion (purple).

- The top six financial centers (London, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Cayman Islands, Ireland) increased their holdings to a record $2.27 trillion.

So on net, foreign holders are still adding to their stash of Treasury securities, with some, such as China and Brazil, unloading; and with others, such as the biggest financial centers, India, and Canada, adding to their stash.

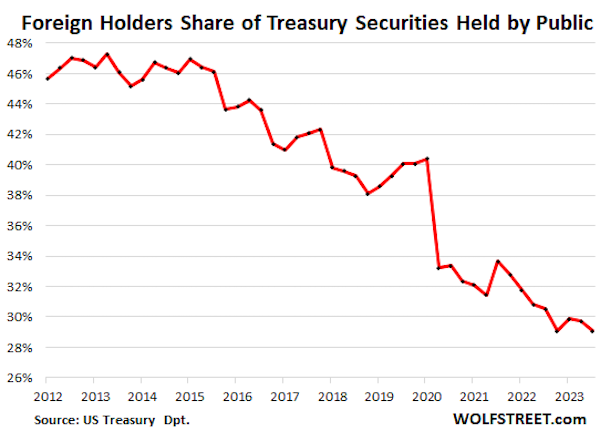

But they haven’t kept up with the US government debt that has been ballooning at an incredible speed in recent years, with trillions whooshing by so fast they’re hard to see.

And so the share of foreign holders of the US debt held by the public has plunged. Ten years ago, they held 45% of the public US debt; but now, despite the increase of their holdings over this period, their share has dropped to 29%.

In other words, they’re still adding, but not nearly fast enough to keep up with the growth of the US debt. And other buyers have to be enticed with higher yields to fill the gap.

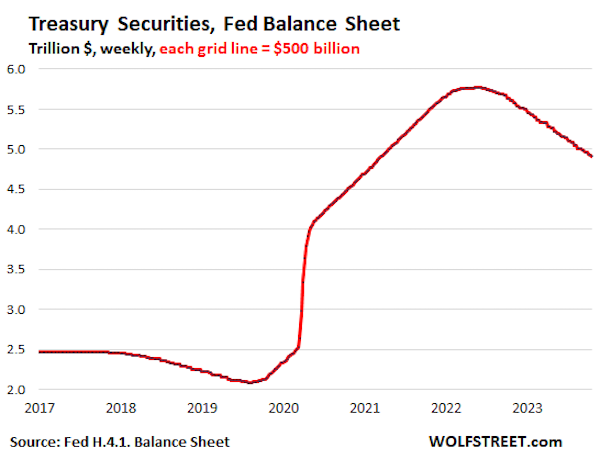

The Fed, oh dear. During the huge binge of QE, when it interfered in the bond market on a daily basis by buying trillions of dollars in Treasury securities of all kinds over the years, the Fed turned into the biggest most relentless bidder in the bond market, thereby repressing yields across the yield curve. Then it ended QE, and did the opposite, QT.

Since ramping up QT to full speed last September 2022, the Fed has been shedding Treasury securities at a rate of about $60 billion a month by letting maturing securities roll off the balance sheet without replacement. Since the peak, it has unloaded $840 billion in Treasury securities, with its Treasury holdings shrinking to $4.91 trillion (we discuss the Fed’s QT in detail monthly, most recently here).

Going from QE, which in the end ran at $120 billion a month, to QT of $60 billion a month, represents a swing of $180 billion a month.

When the government refinances the securities that mature, including those that the Fed held, it must borrow new money to pay off existing creditors, including the Fed. Since the Fed is not buying securities to replace those maturing securities, other buyers must be enticed with higher yields to pick up the slack.

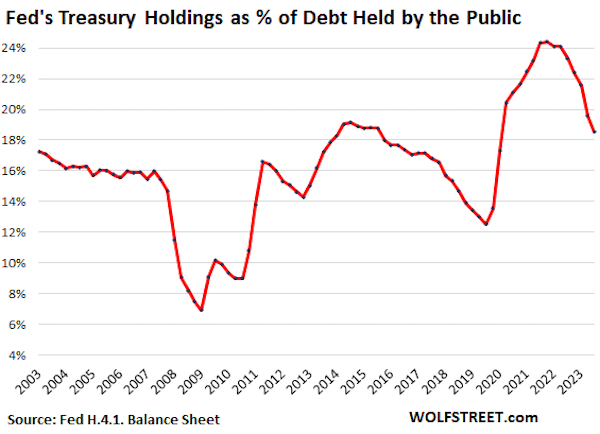

And the share of the Fed’s declining Treasury holdings as a percent of the ballooning pile of government debt held by the public has shrunk to 18.5% currently, from 24.4% in October 2021:

That leaves the rest of the buyers – banks, bond funds, insurance companies, pension funds, other institutional investors, and individuals – to deal with the tsunami of issuance.

Some of them are forced buyers; but others are reluctant buyers that want a decent yield to compensate them appropriately for the risks posed by out-of-control government deficits in an inflationary environment, and they’re looking at the current bloodbath of investors, including banks, that had bought two years ago, and they’re not overeager to bid, but they will bid if the yields are high enough, and that’s what we’re looking at.