The good news: countries have been increasing their ambitions for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The bad news: it’s not nearly enough.

World leaders, scientists, activists and negotiators are gathering in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, for the 27th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP27), this year’s annual global meeting aimed at implementing climate action, including the landmark 2015 Paris Agreement. Current emissions reduction pledges are far short of what is needed to meet the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting warming to “well below” two degrees Celsius, preferably 1.5 degrees C. Under existing pledges, global temperature rise by the end of the century would be about 2.4 to 2.6 degrees C above preindustrial levels, according to a recent United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) report. Given that policies are not even in place yet to meet those pledges, that temperature rise is currently on track to be around 2.8 degrees C.

Every fraction of a degree of warming avoided makes a difference in lessening the ever worsening impacts of the climate crisis. Such changes have already been seen across the globe this year, with heat waves, floods and droughts all exacerbated by rising global temperatures. The window to narrow the gap between what is needed to meet the goals of the Paris climate agreement and what is currently being done is small—about a decade—and quickly closing. “We need to cut emissions as fast as possible. We need to transition to clean energy as fast as possible. We need to stop deforestation as fast as possible. And that’s the case whether you think we can still hit the 1.5-degree target or whether you think that 1.6 degrees or 1.8 degrees or two degrees is locked in,” says Taryn Fransen, a senior fellow at the World Resources Institute and an author of the UNEP report.

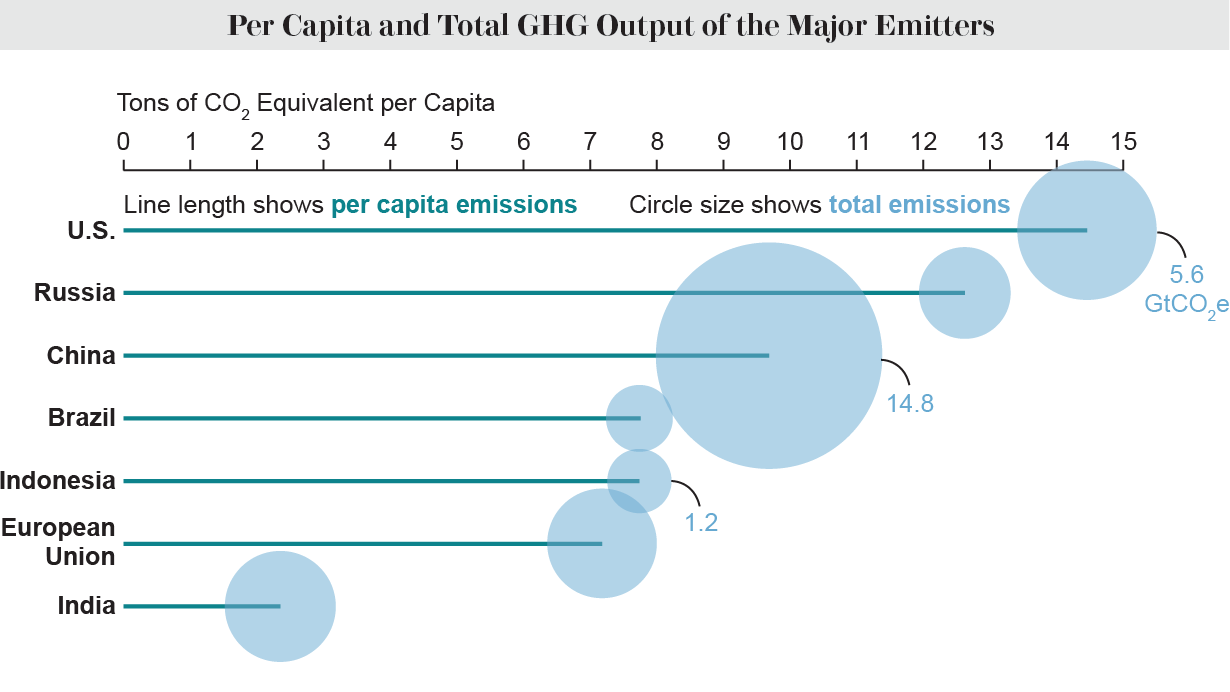

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window–Climate Crisis Calls for Rapid Transformation of Societies. United Nations Environment Program, 2022

Under the Paris Agreement, countries are asked to ramp up the aggressiveness of their emissions reduction goals every five years. These voluntary pledges are known in U.N. parlance as nationally determined contributions (NDCs). At the COP26 meeting held last year in Glasgow, countries were urged to update their pledges on a faster time scale before the COP27 summit. But those updates only account for about 0.5 gigaton of carbon dioxide, or about the average annual emissions of South Africa or Turkey. And some of those pledges came from countries that had not submitted ambitious targets before the Glasgow meeting and so were playing catch-up, Fransen says.

The gap between current pledges and keeping warming to two degrees C is equivalent to about 12 gigatons of CO2—the gap to 1.5 degrees C is an even steeper 20 gigatons.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window–Climate Crisis Calls for Rapid Transformation of Societies. United Nations Environment Program, 2022

But international pledges aren’t the whole story when it comes to reducing emissions—the policies countries enact to actually achieve those pledges are even more important. Some countries, such as the U.S., have pledges above and beyond their domestic policies. When President Joe Biden took office in 2021, he said that the U.S. would reduce its emissions by 50 to 52 percent by 2030. “That was seen as a pretty strong stretch goal for the United States,” Fransen says. “It was something that we—if everything goes right—we can get there.” But until the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) over the summer, the U.S. was lacking the policies to back that up. (The IRA is estimated to reduce U.S. emissions between 30 and 40 percent.)

Conversely, other countries have domestic policies that should achieve more reductions than their current pledges aim for. India, for example, has set a modest NDC but has policies aimed at boosting renewable energy that will easily surpass that goal, Fransen says. Countries such as India are developing economically but cannot have unfettered use of fossil fuels to do so as the U.S. and other developed countries did last century. Renewable energy’s growing cost competitiveness has made that alternative more viable, but installing wind and solar power still requires financing. Some developing countries have made their NDCs contingent on receiving financial support from developed nations. That financing will be a key point of the COP27 talks because developed countries are far behind in providing the money they have pledged for this purpose.

A few countries have indicated they may announce updates to their NDCs during the meeting, but it is highly unlikely they would be anything even close to closing the global gap, Fransen says. Countries need to keep ramping up their ambitions in the next few years, she adds, both through their Paris Agreement pledges and in domestic policies that will bring those to fruition.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the U.N. body that gathers and synthesizes climate research, “has laid out how we can cut emissions in half by 2030 in a cost-effective manner. The technology options are there; it is physically possible,” Fransen says. “In my view, it’s really a question of political judgment.”