It’s not often we see the words “Black pioneer” and “Wild West” in the same sentence. In popular culture, the 19th-century frontier is often associated with white American figures — shoot-’em-up outlaws like Butch Cassidy and fearless folk heroes like Davy Crockett. But there’s one Black mountain man who’s earned his own chapter in the history of westward expansion: James P. Beckwourth.

“I’ve always been impressed with him being an early pioneer, and the people who are pioneers like (explorer) Jedediah Smith,” Everett Brinson says. Brinson, 84, was a member of the James P. Beckwourth Mountain Club in Colorado, which was active from the early 1990s through the late 2000s.

“Beckwourth was … one of their peers and respected by them for his prowess and the fact that he was able to live with the Native Americans and become a war chief,” Brinson says.

Black History Month 2023:Why is Black History Month in February? How do you celebrate? Everything you need to know.

Dive into Black history:10 museums to visit during Black History Month that celebrate culture, history

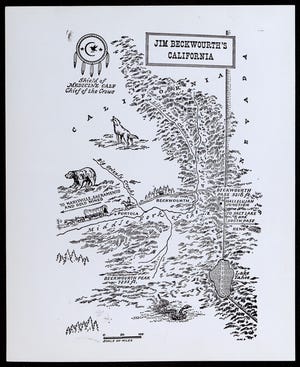

Beckwourth overcame the seemingly impossible. Born into slavery in the late 1700s to a Black mother and a white slaveholder, Beckwourth moved to St. Louis with his father — who freed him as an adult. He joined William Henry Ashley’s fur-trapping company, later known as the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, traveling throughout what is now Montana, Wyoming, Utah and Colorado. Along the way, he befriended Indigenous peoples, such as members of Crow Nation (Apsáalooke), with whom he spent years trapping and selling furs to white traders.

James P. Beckwourth Mountain Club encourages Black people to explore outdoors

He was a founder in 1842 of the El Pueblo trading post in what is now Pueblo, Colorado, and he is credited with discovering a pass in the Sierra Nevada mountain range in 1850. The pass is named for him, as is a nearby city in California.

Inspired by all he achieved, the James P. Beckwourth Mountain Club formed to encourage Black people to live his legacy by exploring the outdoors.

“We were right at the base of the Rockies, and there were all kinds of outdoor trails in Rocky Mountain National Park and all kinds of places for us to hike and enjoy,” Brinson reminisces. “We found that there were a tremendous number of Black people in the Denver metro area who really had a desire for themselves to get into the outdoors and to get children into the outdoors.”

At its peak, the club had more than 300 members, Brinson says.

“Every weekend, we had hikes and outings like going horseback riding and whitewater rafting. In the winter, (we enjoyed) skiing and outdoor skating and outdoor sports,” Brinson says. “To me, it was amazing to see so many Black people interested in doing those kinds of things.”

Although Brinson says the club no longer exists, a passionate community of Beckwourth admirers continues to study and promote his accomplishments. When the movie “The Harder They Fall”, containing a fictionalized version of Beckwourth’s character, was released in 2021, the community was dismayed.

“They took a number of the characters who were prominent in the West, and they put them all in one film. James Beckwourth was actually born in the late 1700s, and there were other people in that film who were born in the (1800s),” Brinson says, referencing Nat Love, an American cowboy and former enslaved person who was born in the 1850s, the outlaw Rufus Buck Gang of the 1890s, and Stagecoach Mary, who was born in the 1830s. “They made Beckwourth a character as a young man in there. We were unhappy that he wasn’t portrayed well, and other people were portrayed very well.”

Brinson says Beckwourth deserves a film that honors his legacy.

“All of us want the story to be told, and to be told well,” he says.